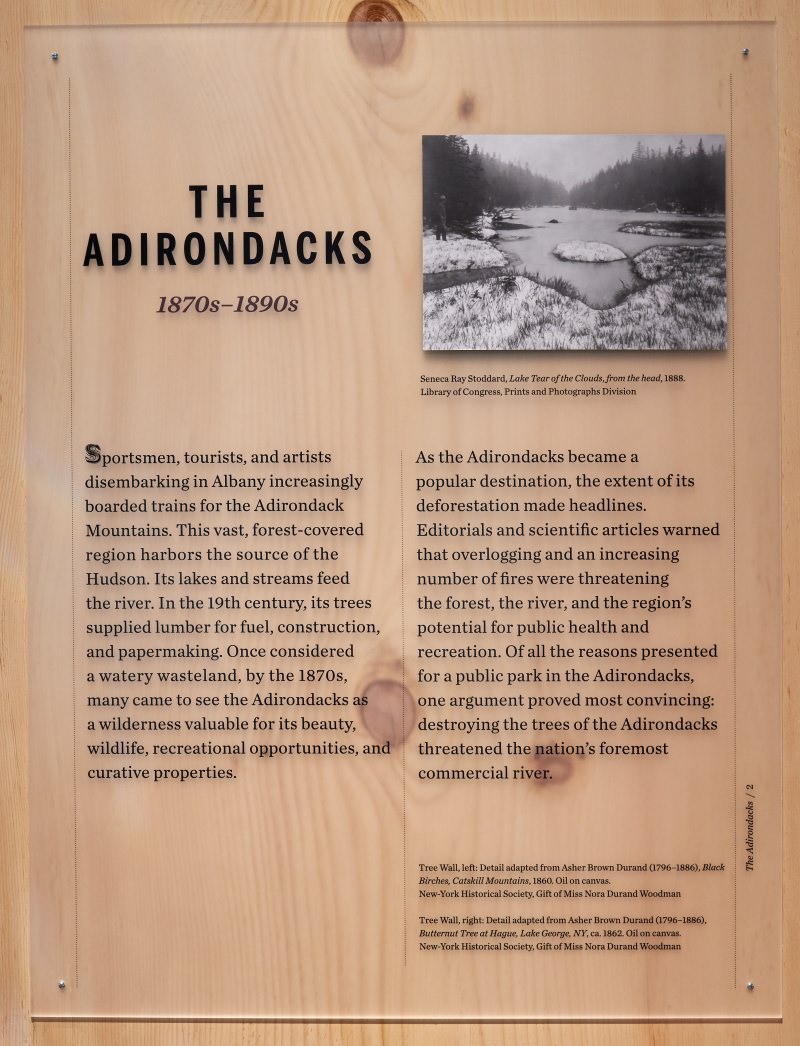

The Adirondacks: 1870s–1890s

Sportsmen, tourists, and artists disembarking in Albany increasingly boarded trains for the Adirondack Mountains. This vast, forest-covered region harbors the source of the Hudson. Its lakes and streams feed the river. In the 19th century, its trees supplied lumber for fuel, construction, and papermaking. Once considered a watery wasteland, by the 1870s, many came to see the Adirondacks as a wilderness valuable for its beauty, wildlife, recreational opportunities, and curative properties.

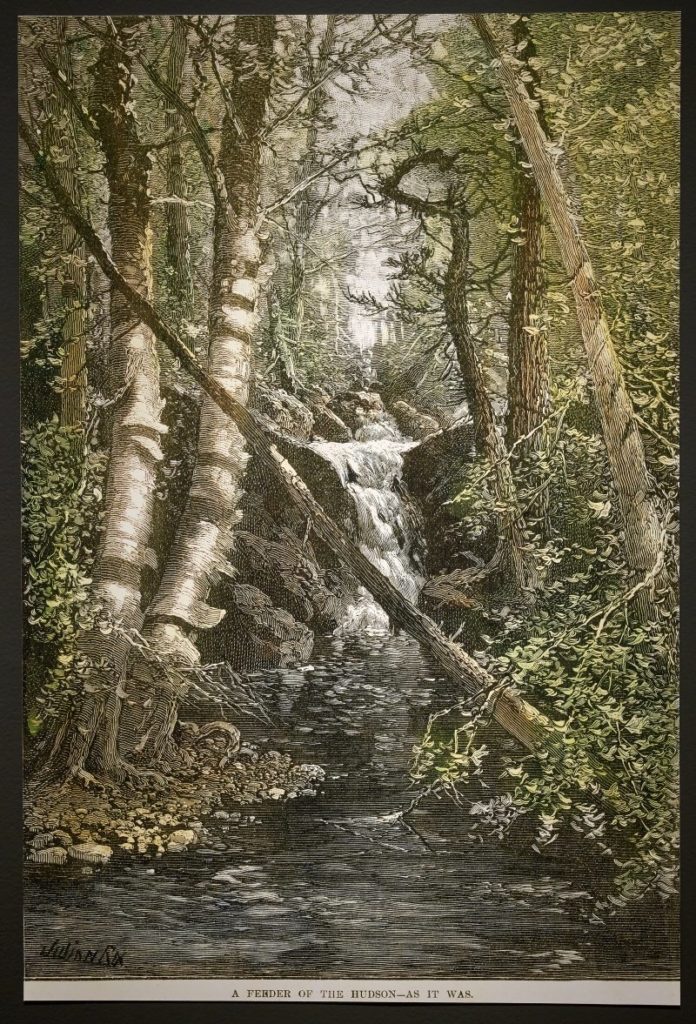

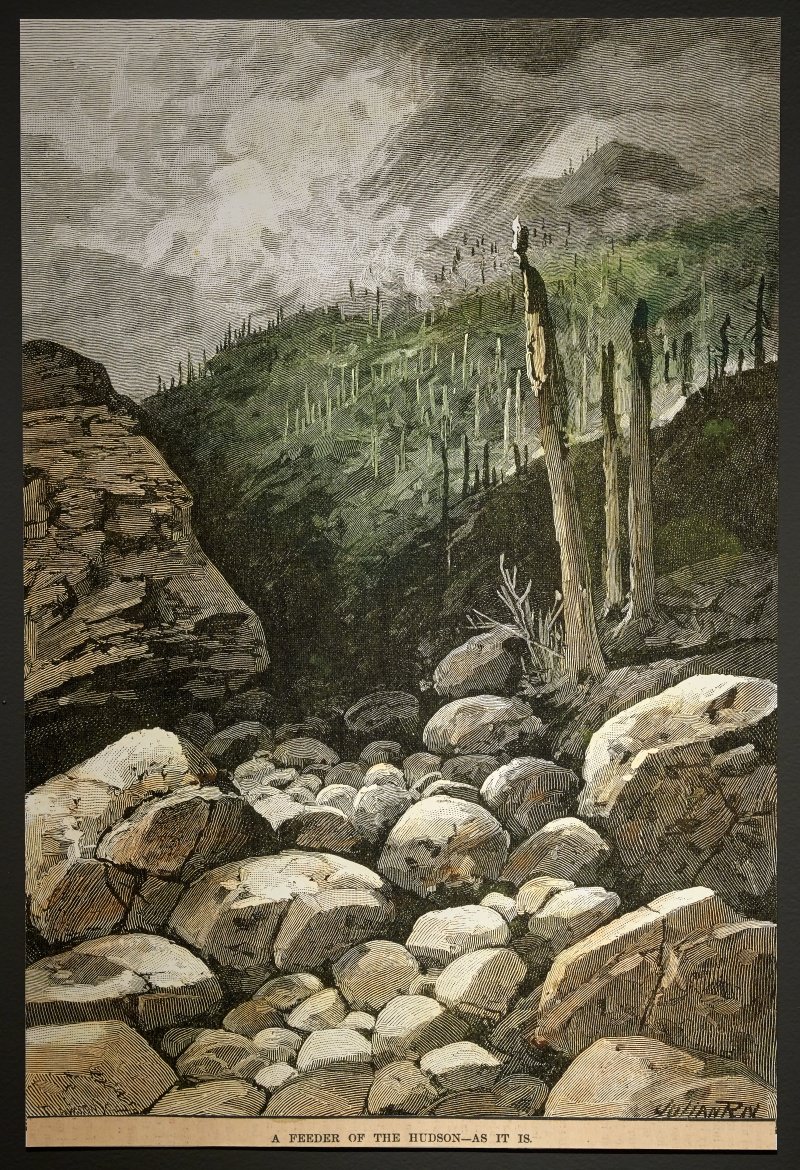

As the Adirondacks became a popular destination, the extent of its deforestation made headlines. Editorials and scientific articles warned that overlogging and an increasing number of fires were threatening the forest, the river, and the region’s potential for public health and recreation. Of all the reasons presented for a public park in the Adirondacks, one argument proved most convincing: destroying the trees of the Adirondacks threatened the nation’s foremost commercial river.

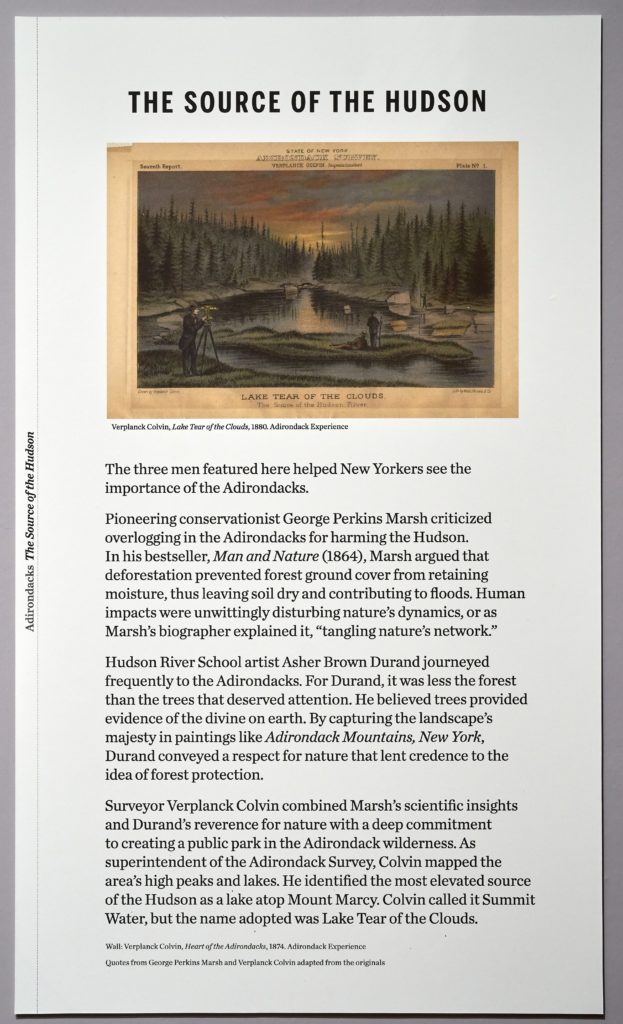

The Source of the Hudson

The three men featured here helped New Yorkers see the importance of the Adirondacks.

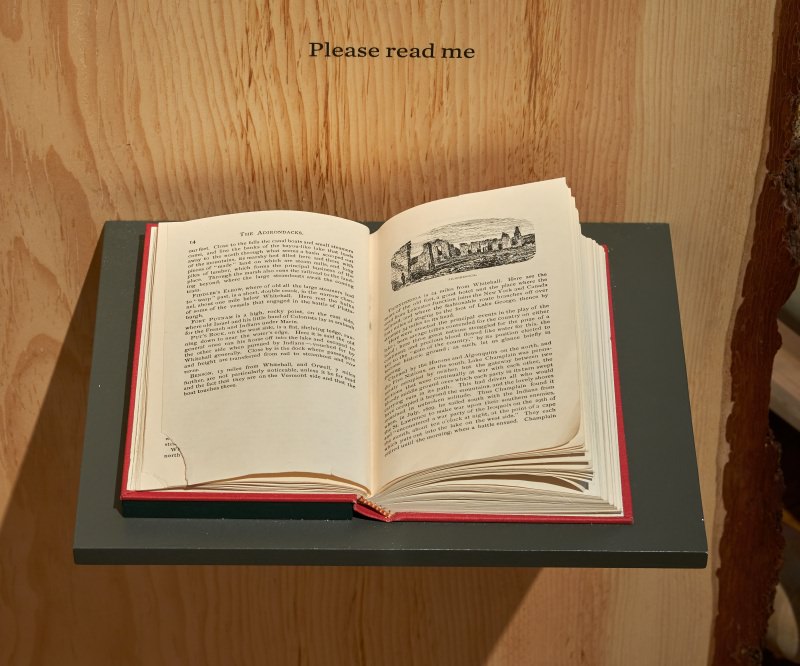

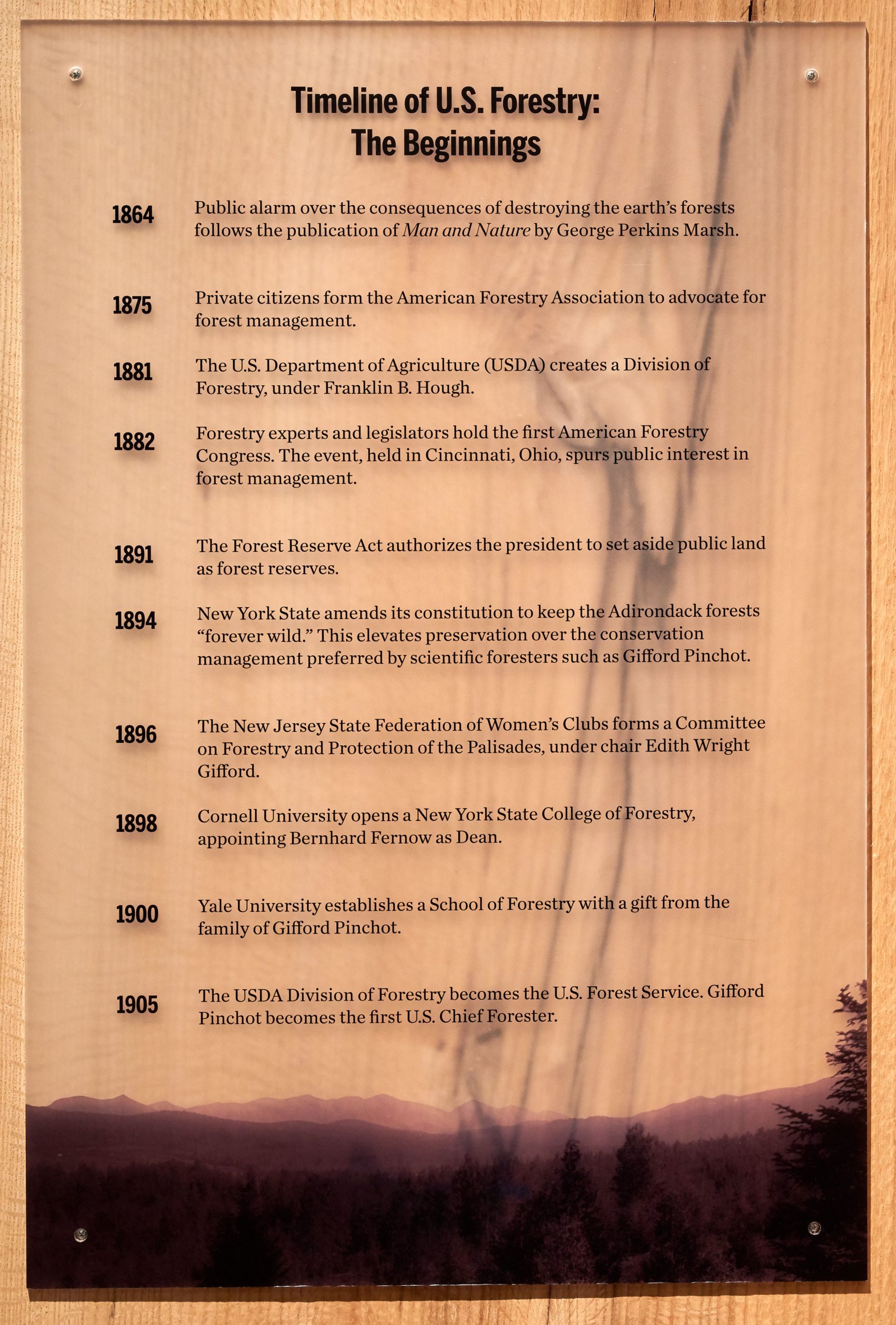

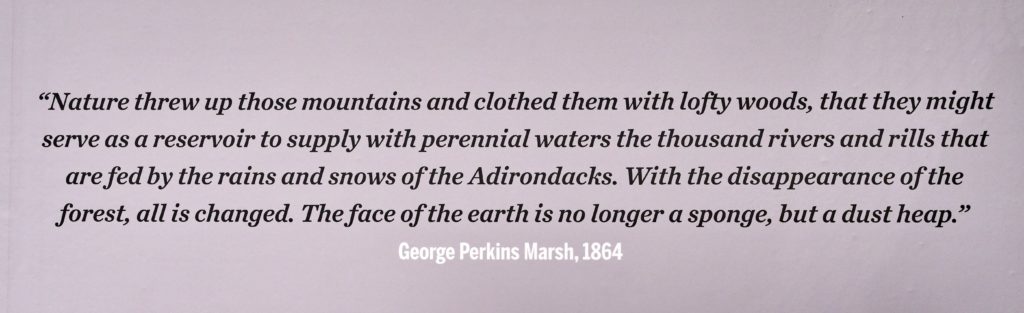

Pioneering conservationist George Perkins Marsh criticized overlogging in the Adirondacks for harming the Hudson. In his bestseller, Man and Nature (1864), Marsh argued that deforestation prevented forest ground cover from retaining moisture, thus leaving soil dry and contributing to floods. Human impacts were unwittingly disturbing nature’s dynamics, or as Marsh’s biographer explained it, “tangling nature’s network.”

Hudson River School artist Asher Brown Durand journeyed frequently to the Adirondacks. For Durand, it was less the forest than the trees that deserved attention. He believed trees provided evidence of the divine on earth. By capturing the landscape’s majesty in paintings like Adirondack Mountains, New York, Durand conveyed a respect for nature that lent credence to the idea of forest protection.

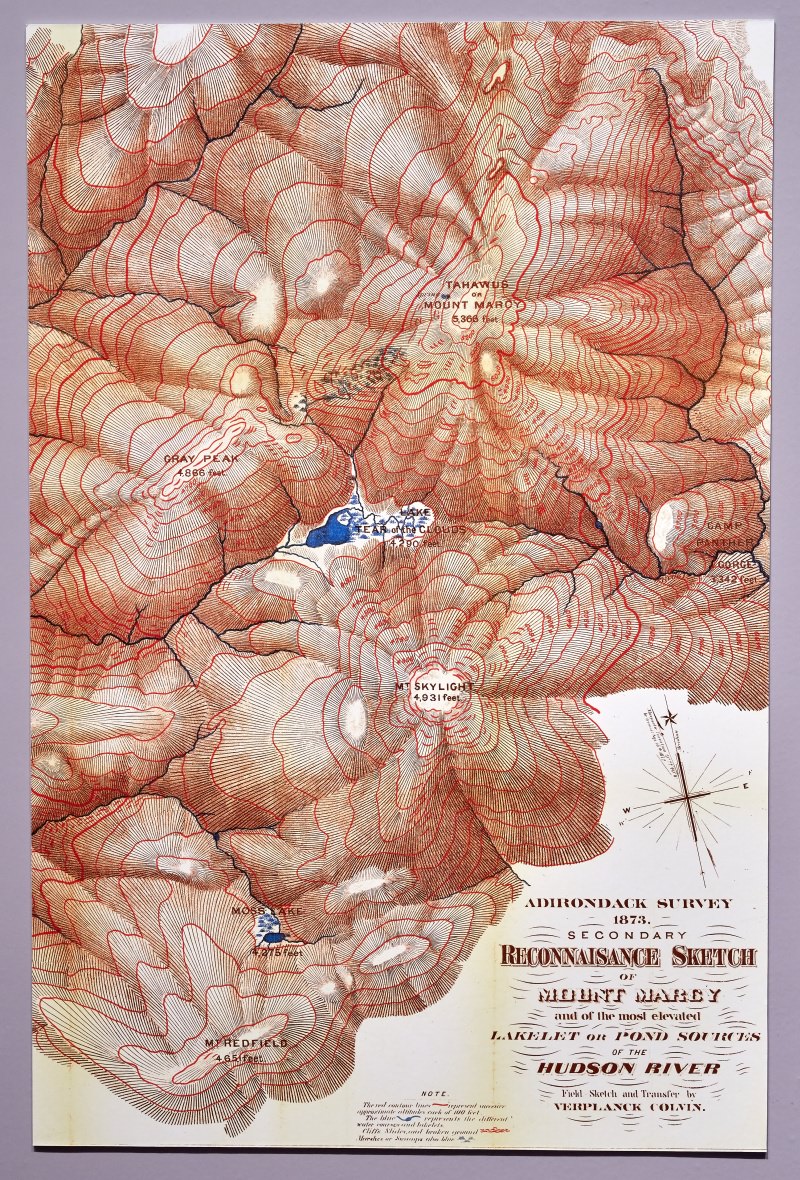

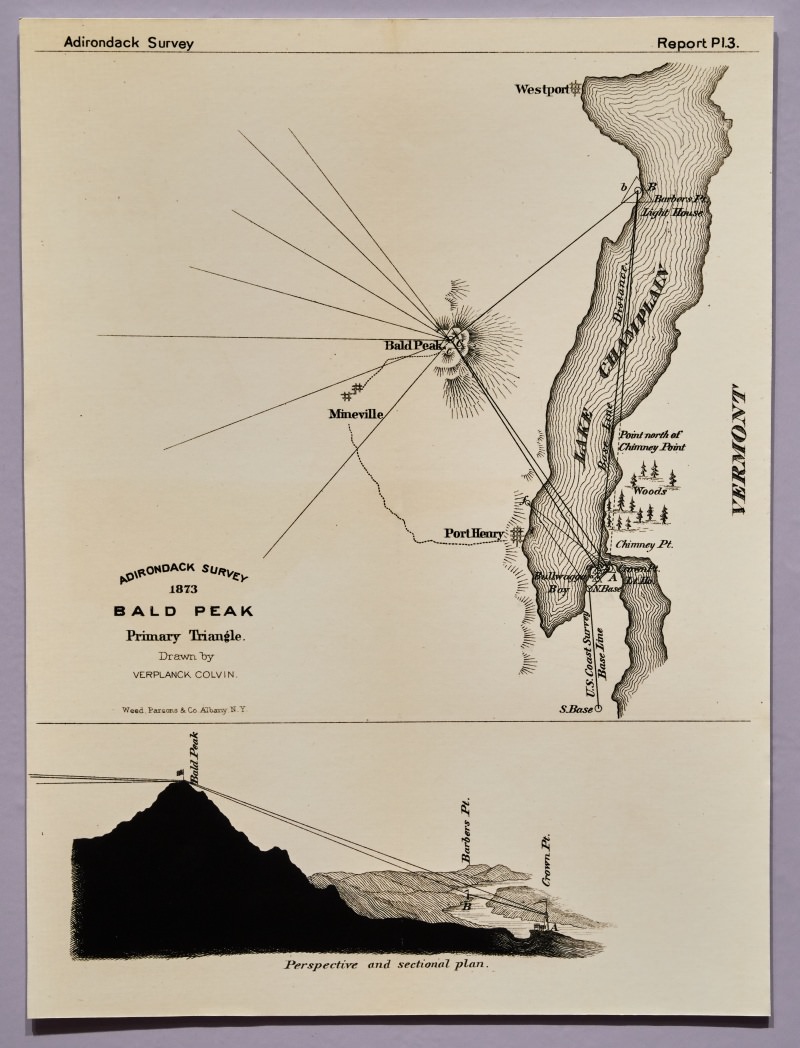

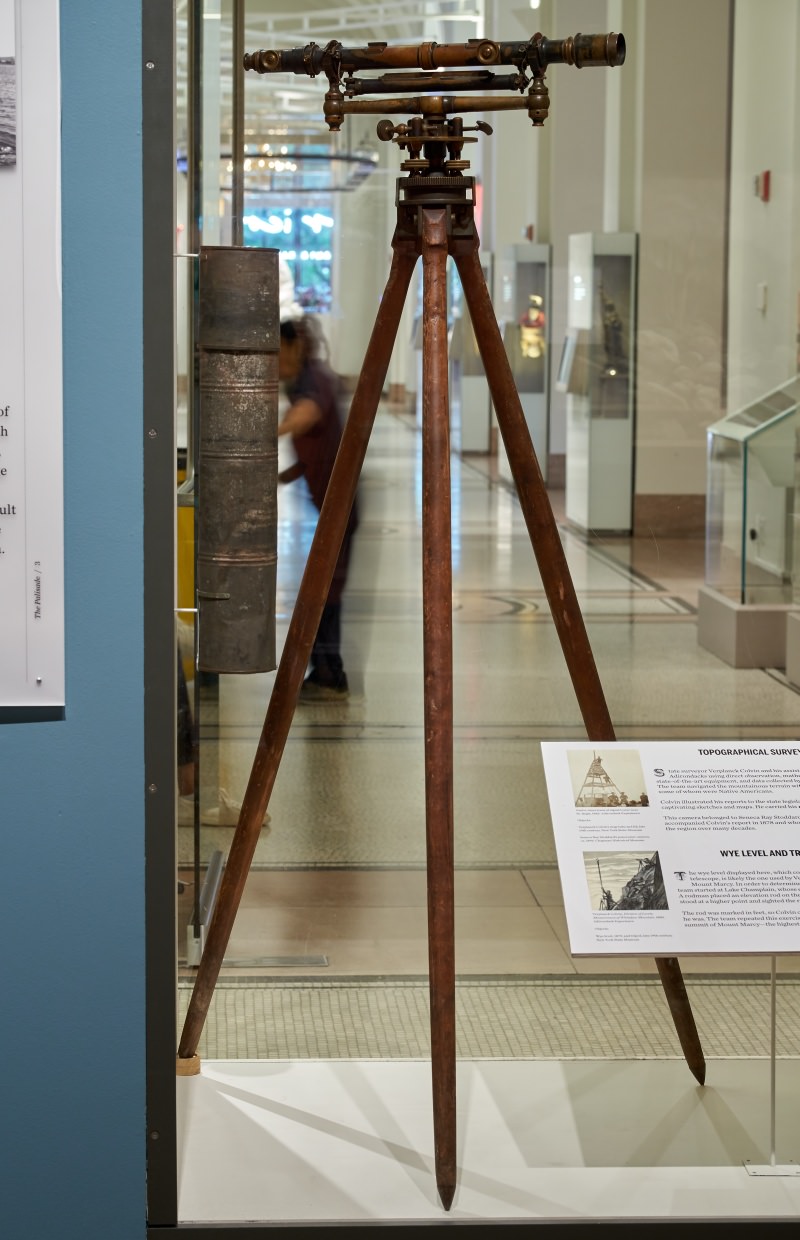

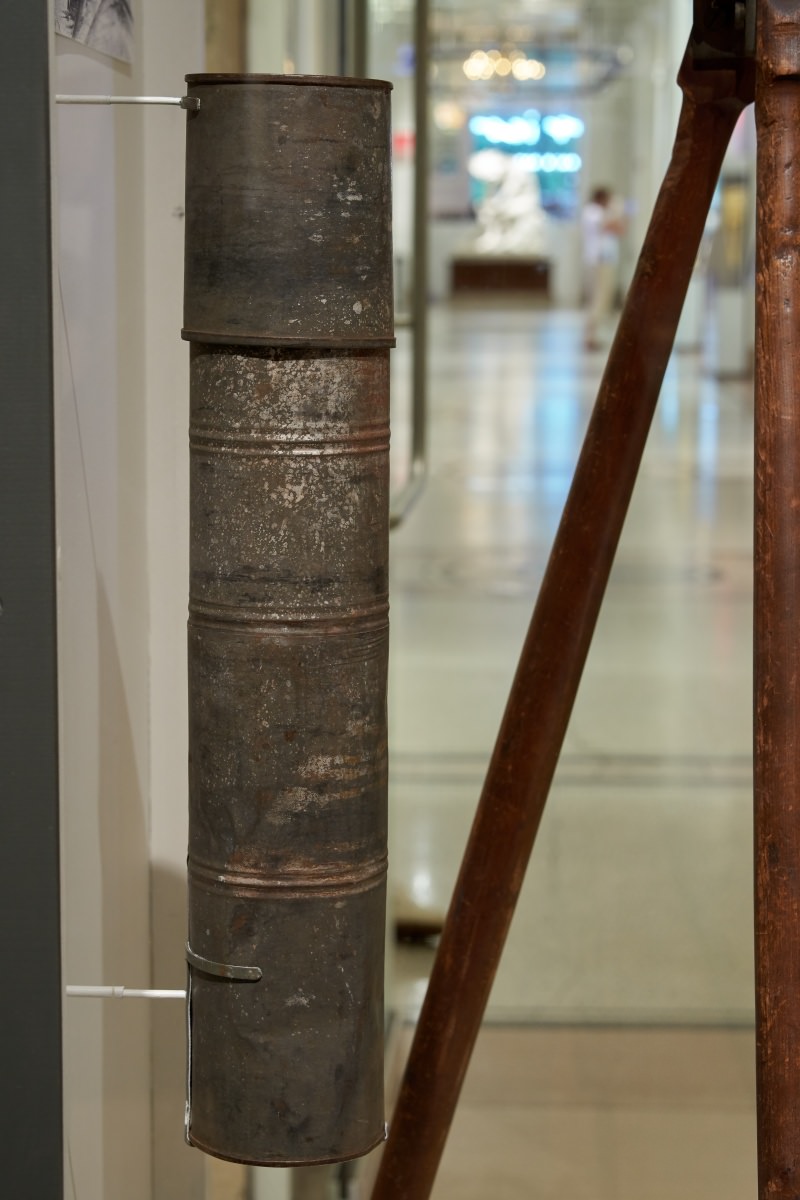

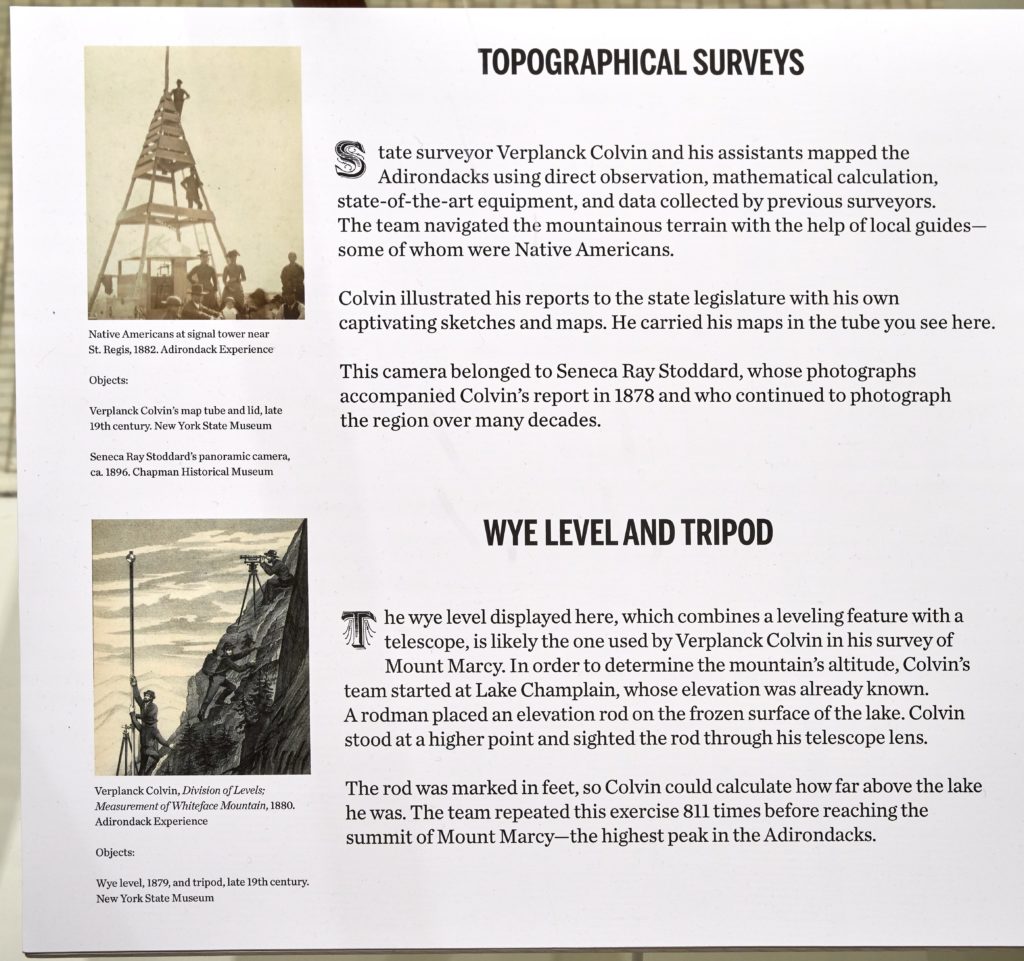

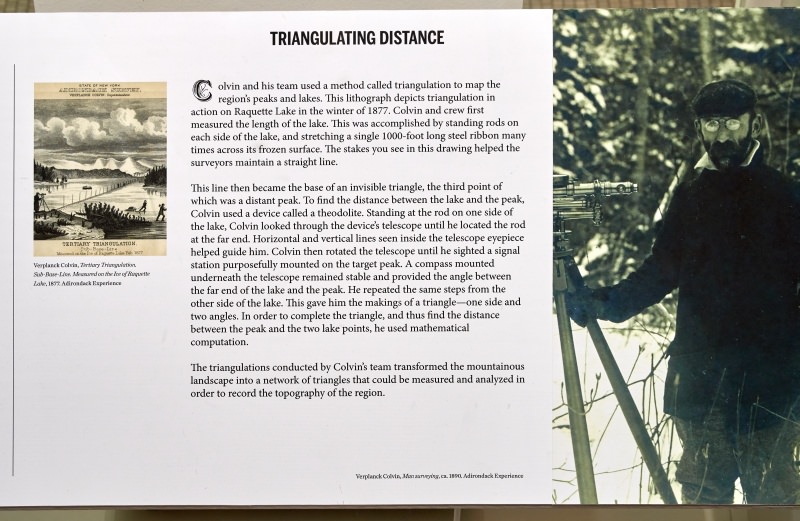

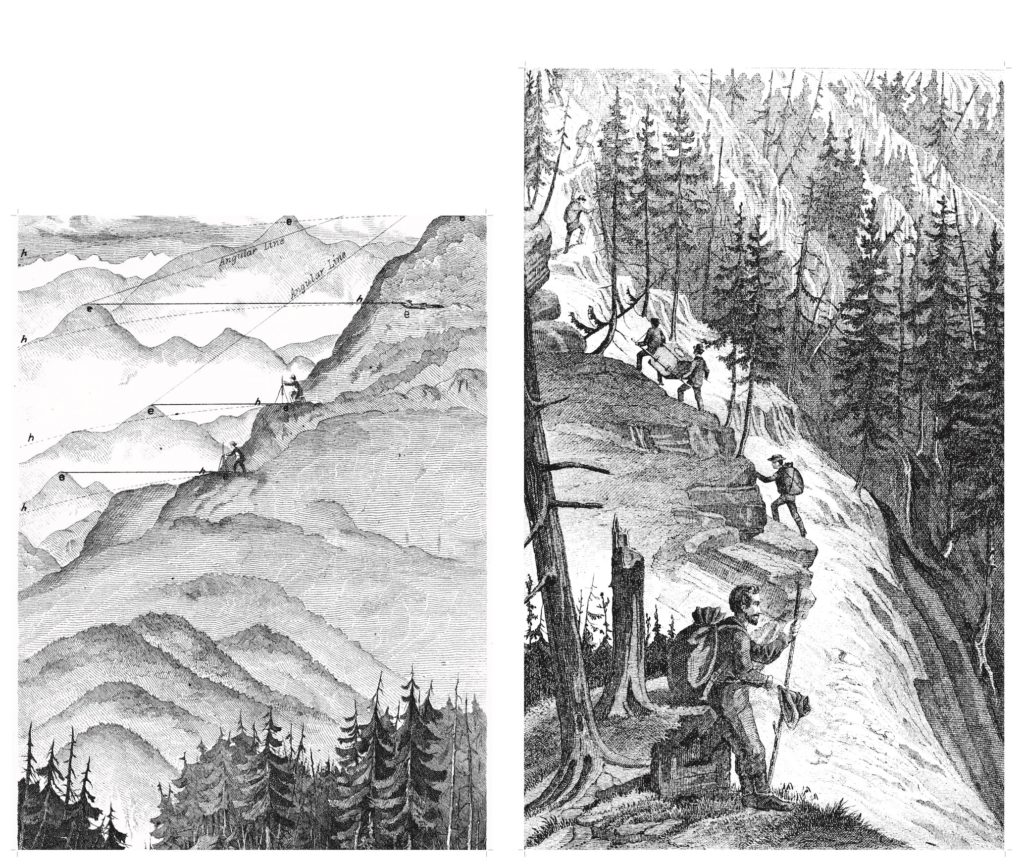

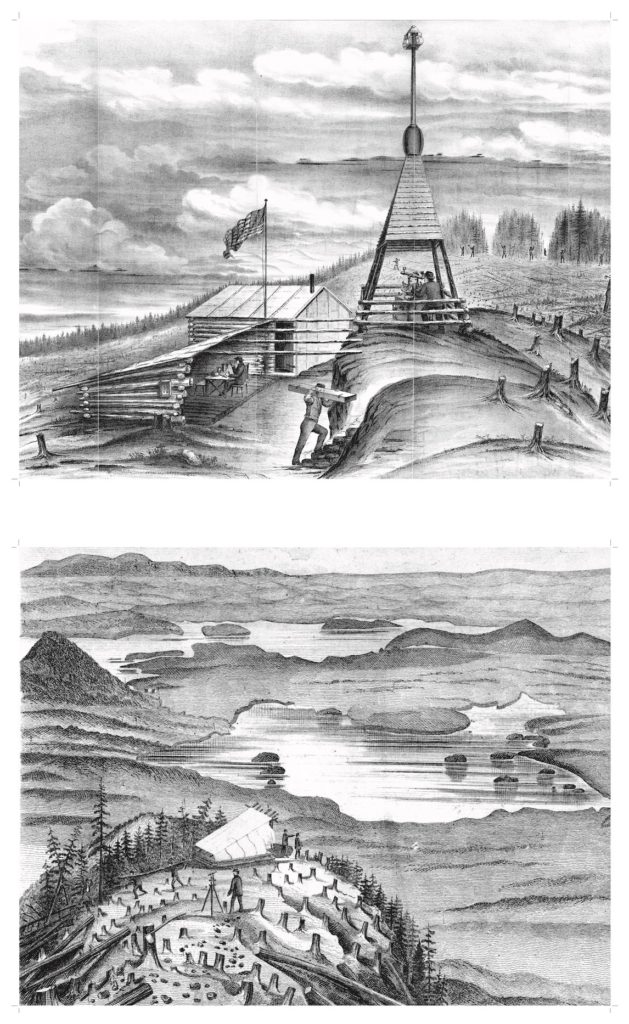

Surveyor Verplanck Colvin combined Marsh’s scientific insights and Durand’s reverence for nature with a deep commitment to creating a public park in the Adirondack wilderness. As superintendent of the Adirondack Survey, Colvin mapped the area’s high peaks and lakes. He identified the most elevated source of the Hudson as a lake atop Mount Marcy. Colvin called it Summit Water, but the name adopted was Lake Tear of the Clouds.

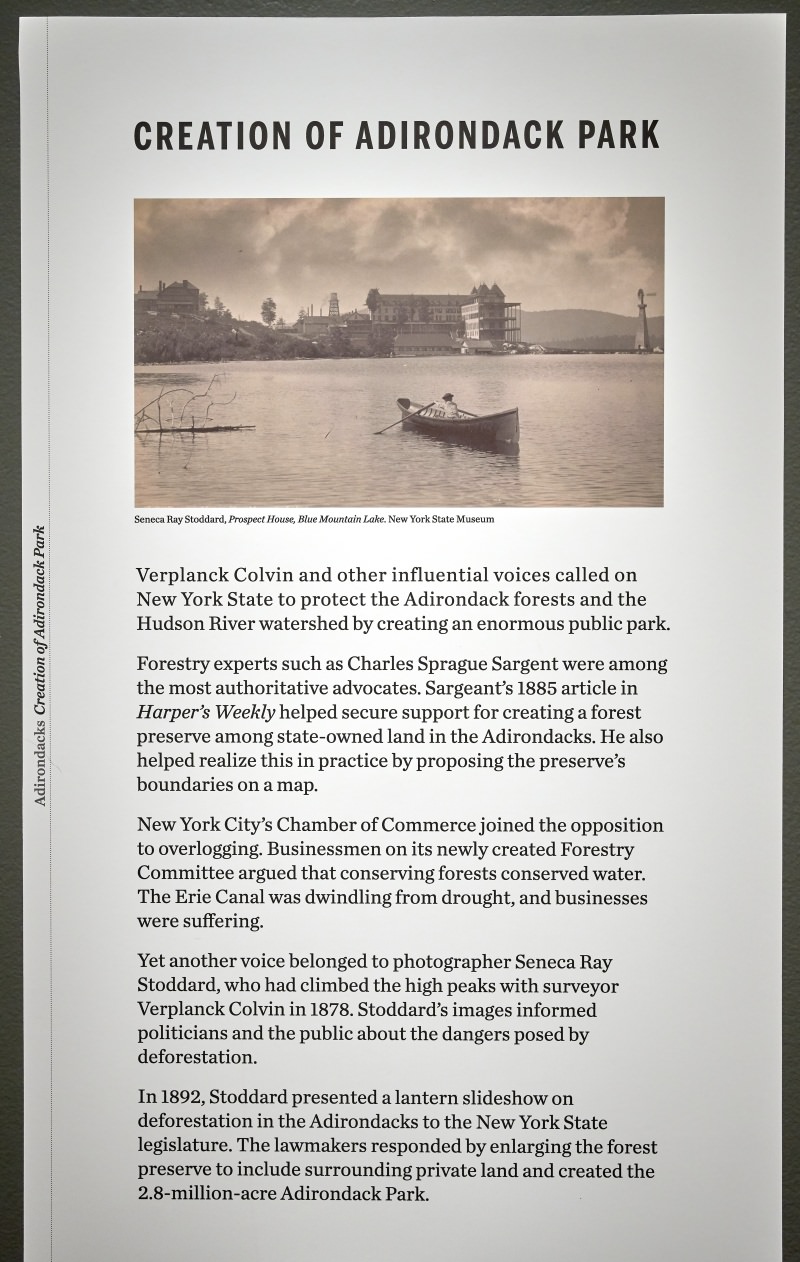

Creation of Adirondack Park

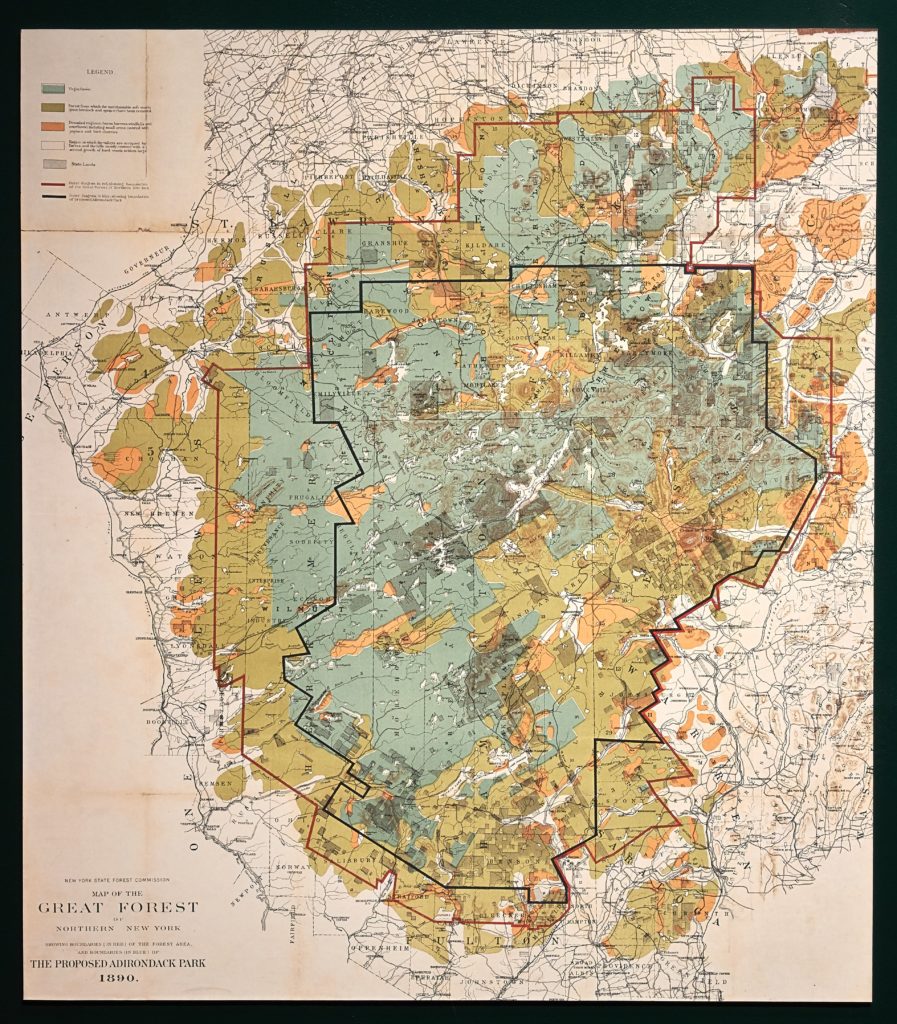

Verplanck Colvin and other influential voices called on New York State to protect the Adirondack forests and the Hudson River watershed by creating an enormous public park.

Forestry experts such as Charles Sprague Sargent were among the most authoritative advocates. Sargeant’s 1885 article in Harper’s Weekly helped secure support for creating a forest preserve among state-owned land in the Adirondacks. He also helped realize this in practice by proposing the preserve’s boundaries on a map.

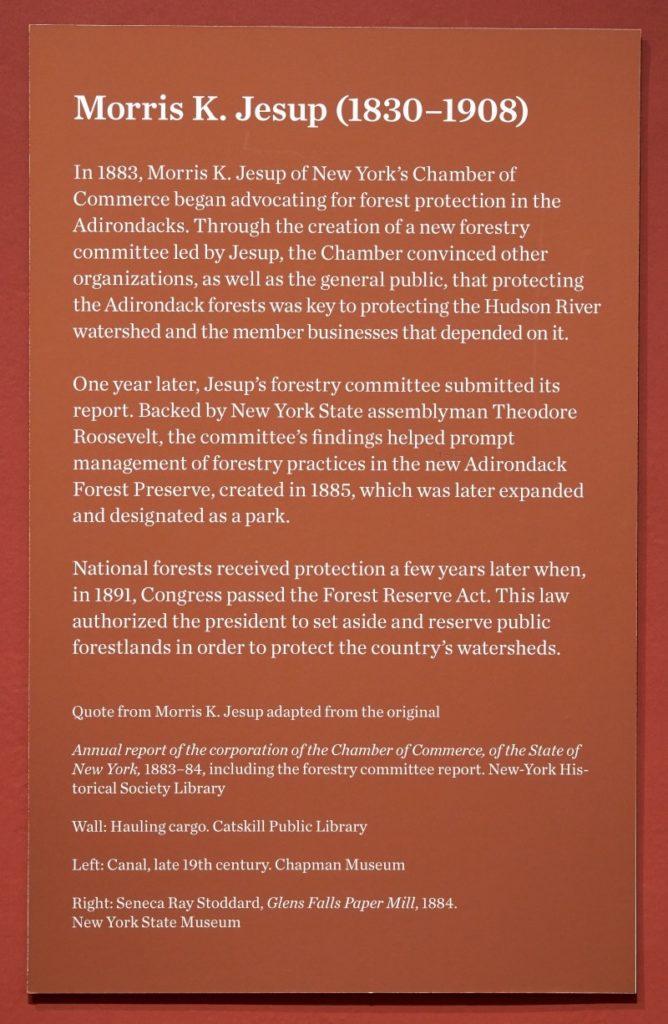

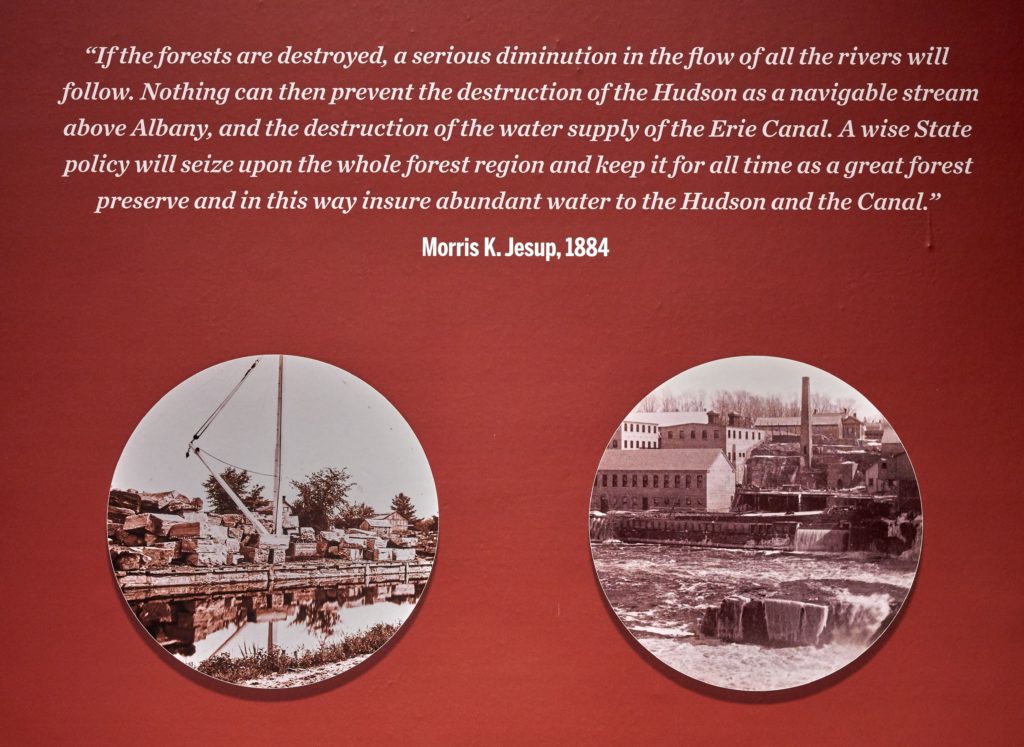

New York City’s Chamber of Commerce joined the opposition to overlogging. Businessmen on its newly created Forestry Committee argued that conserving forests conserved water. The Erie Canal was dwindling from drought, and businesses were suffering.

Yet another voice belonged to photographer Seneca Ray Stoddard, who had climbed the high peaks with surveyor Verplanck Colvin in 1878. Stoddard’s images informed politicians and the public about the dangers posed by deforestation.

In 1892, Stoddard presented a lantern slideshow on deforestation in the Adirondacks to the New York State legislature. The lawmakers responded by enlarging the forest preserve to include surrounding private land and created the 2.8-million-acre Adirondack Park.

Reclaimed live-edge slab of Red Oak (Quercus rubra) obtained from the Lower Hudson Valley and live-edge slab of Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) obtained from the Adirondacks by artist/woodworker Timothy Englert

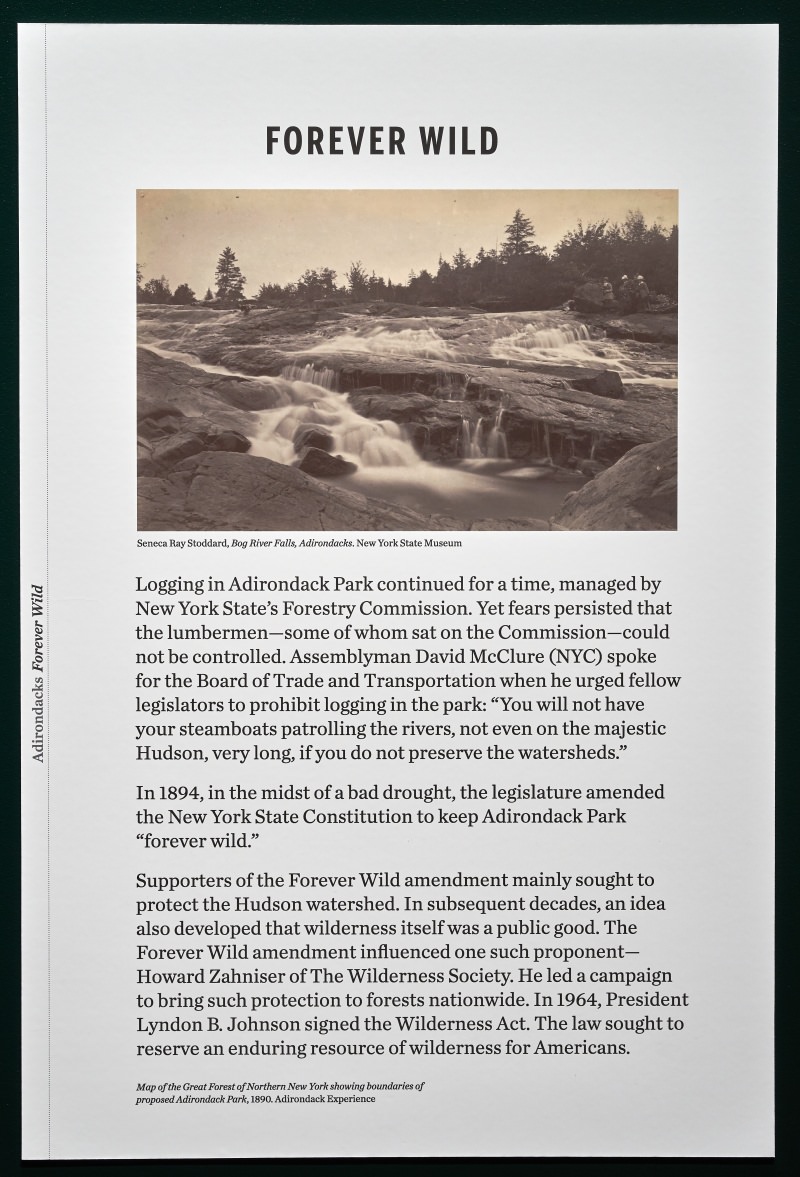

Forever Wild

Logging in Adirondack Park continued for a time, managed by New York State’s Forestry Commission. Yet fears persisted that the lumbermen—some of whom sat on the Commission—could not be controlled. Assemblyman David McClure (NYC) spoke for the Board of Trade and Transportation when he urged fellow legislators to prohibit logging in the park: “You will not have your steamboats patrolling the rivers, not even on the majestic Hudson, very long, if you do not preserve the watersheds.”

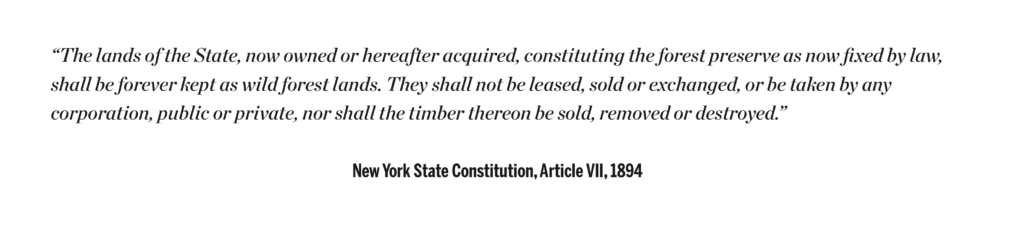

In 1894, in the midst of a bad drought, the legislature amended the New York State Constitution to keep Adirondack Park “forever wild.”

Supporters of the Forever Wild amendment mainly sought to protect the Hudson watershed. In subsequent decades, an idea also developed that wilderness itself was a public good. The Forever Wild amendment influenced one such proponent—Howard Zahniser of The Wilderness Society. He led a campaign to bring such protection to forests nationwide. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act. The law sought to reserve an enduring resource of wilderness for Americans.