A Rising Tide: Today

What is changing along the Hudson?

Industries that once propelled development along the river no longer drive the economy. Hudson River cities and towns are reimagining themselves in order to stay viable. One of their

biggest assets is the appeal of the landscape itself.

The river is now clean enough for kayakers and healthy enough for some species of fish to begin their return. Its banks are largely free of trash, and special vistas mostly cleared of obstructions. These improvements owe much to the environmental activism of the 1960s and ‘70s. But the task of reclaiming the Hudson from the legacy of pollution continues.

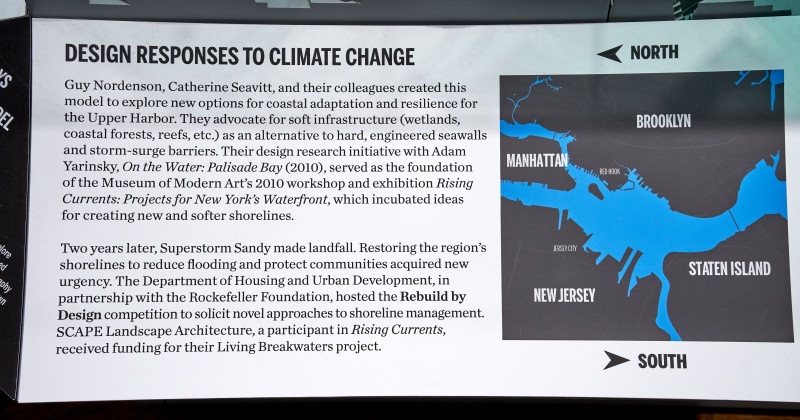

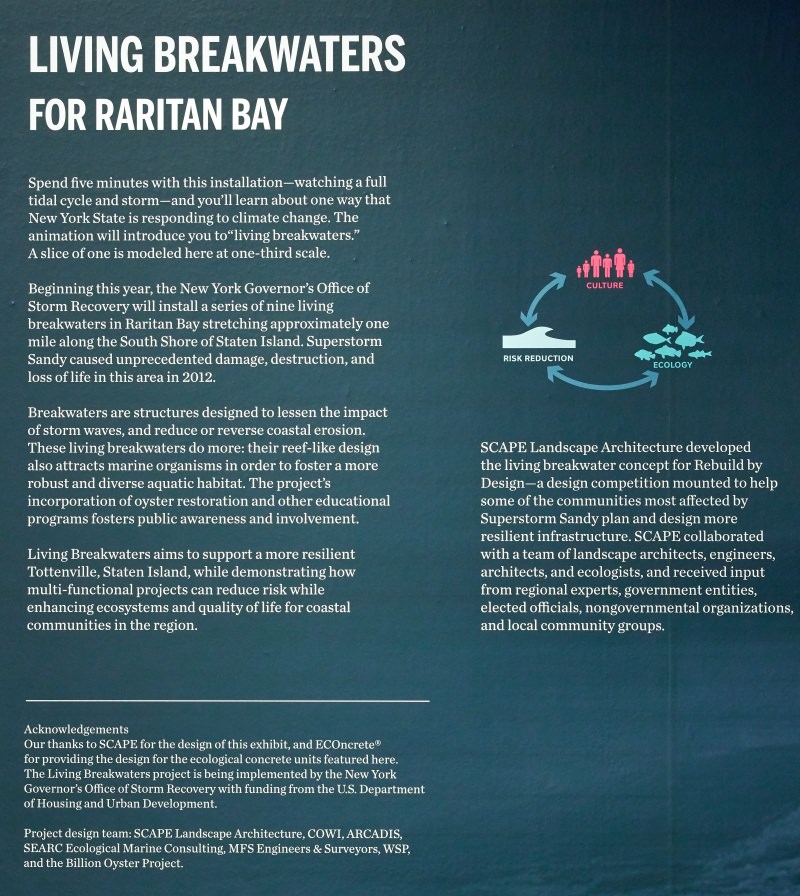

As part of adapting to climate change, professionals in many fields are restoring the river’s shallows and reengineering its marshlands. These areas are the nurseries for aquatic life. They also improve water quality and lessen the impact of storm surges and flooding.

Two hundred years ago, Hudson River steamboats helped initiate an industrial, fossil fuel-driven age. We all now live with its impacts both positive and negative. What climate change portends for the Hudson is still unfolding, but if history is any guide, it’s a landscape worth protecting.

Reimagining

The steady departure of riverfront industries since the 1960s has propelled Hudson Valley towns to reimagine how the landscape’s beauty and history can foster prosperity once again.

Riverfronts to Waterfronts

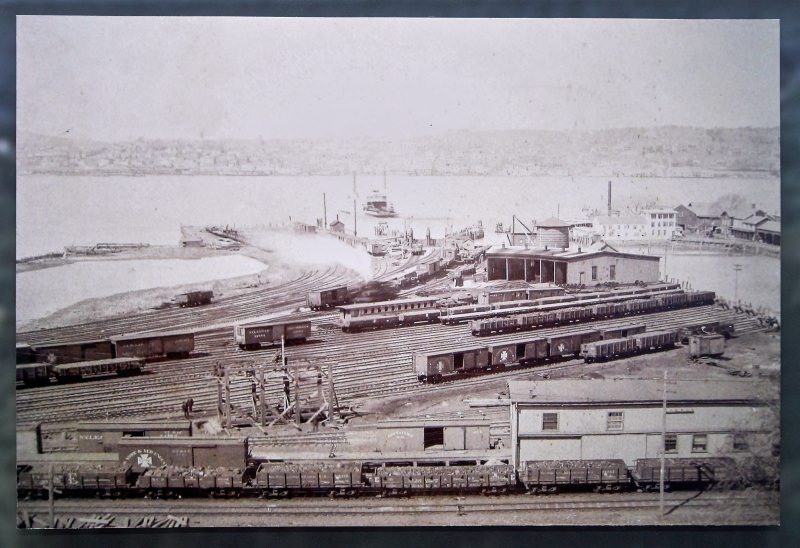

The cities and towns of the Hudson estuary, from New York City to Troy, maintained their prosperous industrial riverfronts well into the 1960s. Then came the one-two punch: the decline of manufacturing and port-related activities, along with the loss of downtowns to shopping malls and urban renewal. Municipal finances collapsed. Elected officials struggled to cope with abandoned structures and land poisoned by toxic wastes.

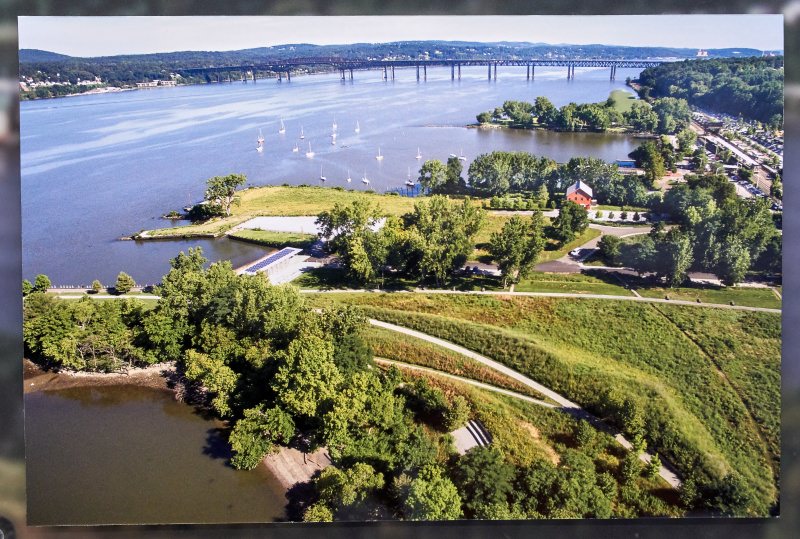

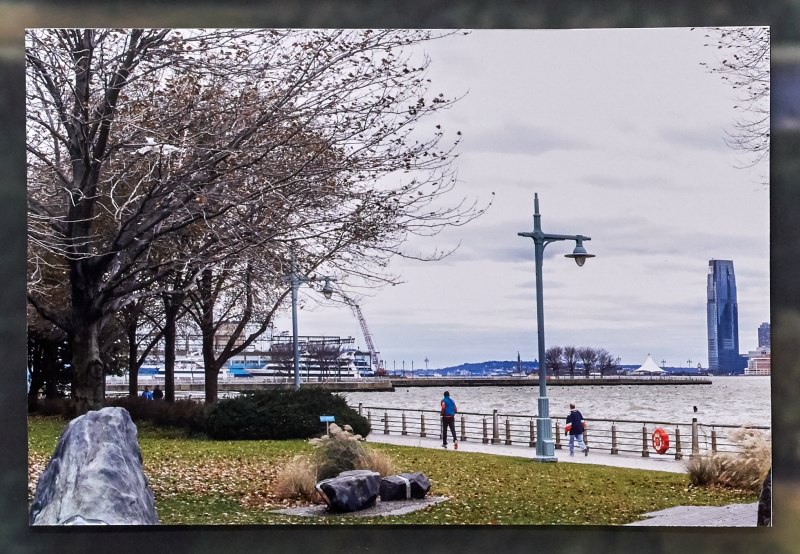

The recovery has been long and hard. These before-and-after images of New York City and Beacon show approaches to waterfront revitalization that offer more than meets the eye. What you see are lovely parks and amenities. What you get are landscapes that also reintroduce floodplains, restore healthy aquatic habitats, rebuild local economies, and reignite citizen interest in the river.

Long Dock Park in Beacon and Hudson River Park in New York City are part of a region-wide greenway initiative that is conserving recreational and natural areas along both sides of the river as part of the federally designated Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area.

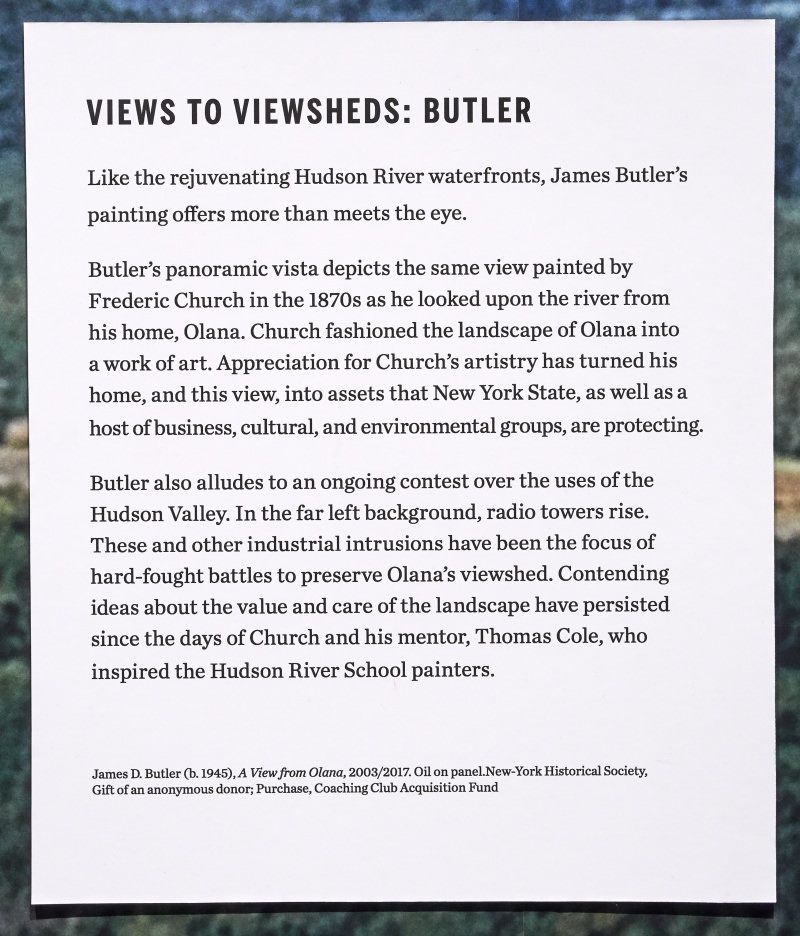

Views to Viewsheds: Butler

Like the rejuvenating Hudson River waterfronts, James Butler’s painting offers more than meets the eye.

Butler’s panoramic vista depicts the same view painted by Frederic Church in the 1870s as he looked upon the river from his home, Olana. Church fashioned the landscape of Olana into a work of art. Appreciation for Church’s artistry has turned his home, and this view, into assets that New York State, as well as a host of business, cultural, and environmental groups, are protecting.

Butler also alludes to an ongoing contest over the uses of the Hudson Valley. In the far left background, radio towers rise. These and other industrial intrusions have been the focus of hard-fought battles to preserve Olana’s viewshed. Contending ideas about the value and care of the landscape have persisted since the days of Church and his mentor, Thomas Cole, who inspired the Hudson River School painters.

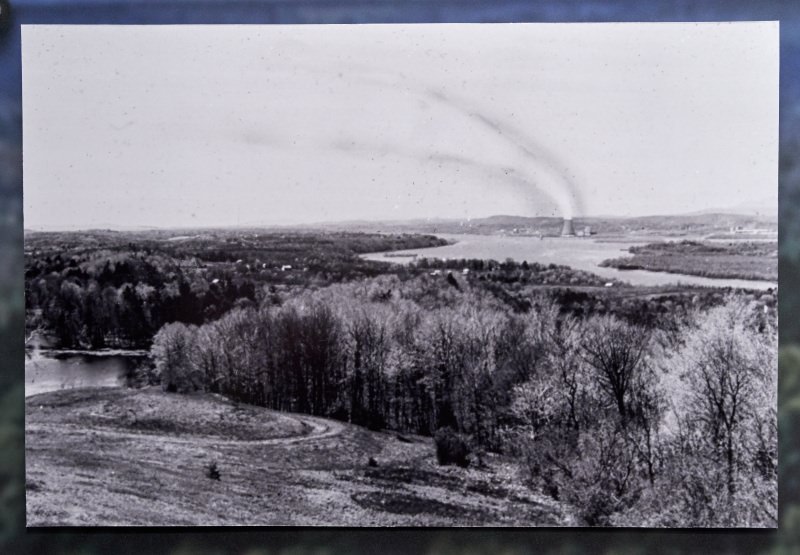

Views to Viewsheds: Church

In the 19th century, Frederic Church frequently painted this view from his home, Olana. Church’s passion for the view, and his fame as an artist, made this scenic landscape an icon of the Hudson River School of art. When a nuclear power plant promised to intrude upon the view in the early 1970s, citizen-led groups protested.

The National Environmental Policy Act, passed in 1969, required consideration of the plant’s impact on the environment. But how to determine the value of a view? You see it here. Consultants prepared versions of the view with the plant’s cooling tower obviously drawn in. Then they showed the mock-ups to local residents and had them record their responses in a survey. This method of viewshed analysis produced data that could be measured and used as evidence.

The survey responses and this very painting by Church helped to convince the government reviewers that the power plant would have an unacceptable negative impact on the scenic and historic character of Olana—a place determined to be of national significance. No license for the plant was issued.

Reclaiming

Hard work and strong laws halted the Hudson’s downward spiral. But reclaiming the river from the scourge of PCBs has put the dream of clean, safe water to its toughest test.

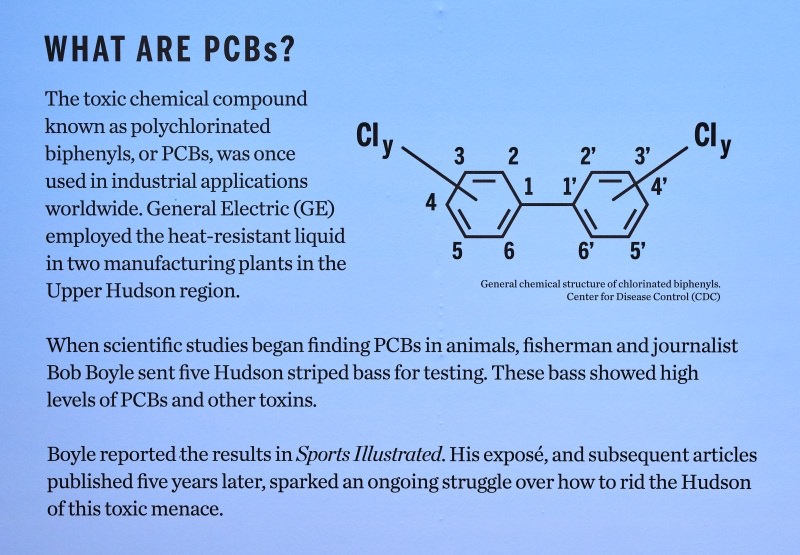

What Are PCBs?

The toxic chemical compound known as polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, was once used in industrial applications worldwide. General Electric (GE) employed the heat- resistant liquid in two manufacturing plants in the Upper Hudson region.

When scientific studies began finding PCBs in animals, fisherman and journalist Bob Boyle sent five Hudson striped bass for testing. These bass showed high levels of PCBs and other toxins.

Boyle reported the results in Sports Illustrated. His exposé, and subsequent articles published five years later, sparked an ongoing struggle over how to rid the Hudson of this toxic menace

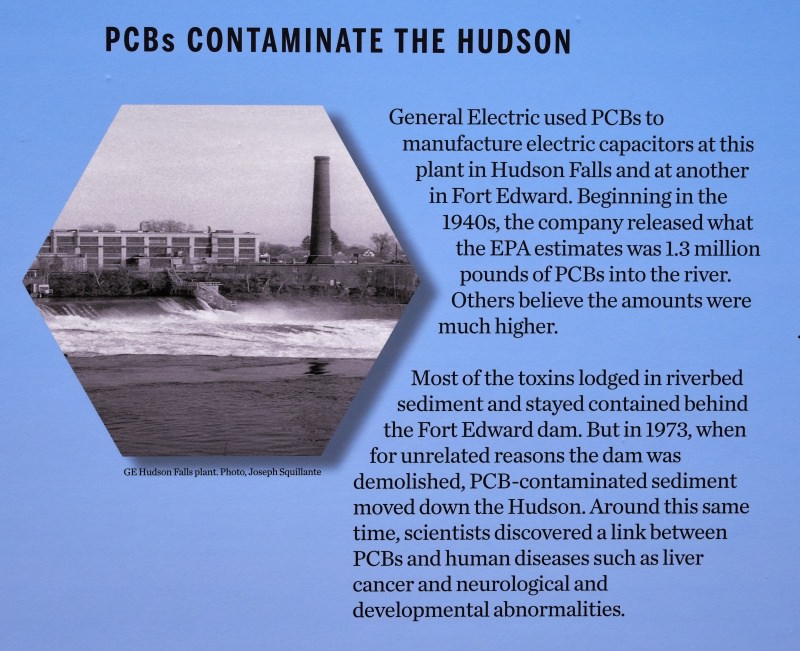

PCBs Contaminate the Hudson

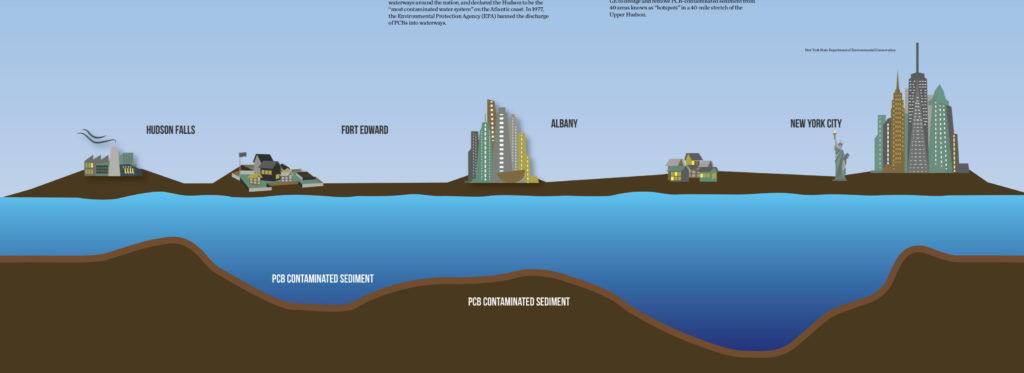

General Electric used PCBs to manufacture electric capacitors at this plant in Hudson Falls and at another in Fort Edward. Beginning in the 1940s, the company released what the EPA estimates was 1.3 million pounds of PCBs into the river. Others believe the amounts were much higher.

Most of the toxins lodged in riverbed sediment and stayed contained behind the Fort Edward dam. But in 1973, when for unrelated reasons the dam was demolished, PCB-contaminated sediment moved down the Hudson. Around this same time, scientists discovered a link between PCBs and human diseases such as liver cancer and neurological and developmental abnormalities.

Sounding the Alarm

Additional mishaps worsened the river-wide PCB contamination. State officials issued warnings against eating striped bass and certain other Hudson River fish.

Still, GE denied responsibility, and federal agencies took little action. Bob Boyle reported on both. Two 1975 Sports Illustrated articles galvanized national attention. Government authorities found severe contamination in waterways around the nation and declared the Hudson to be the “most contaminated water system” on the Atlantic coast. In 1977, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned the discharge of PCBs into waterways.

Becoming a Superfund Site

The Hudson was one of many places around the country contaminated with hazardous wastes. In 1980, Congress passed the Superfund Act. This law empowers the government to designate hazardous sites and requires polluters to pay cleanup costs.

Four years later, the EPA designated a 200-mile stretch of the river, from Hudson Falls to Manhattan’s Battery, as a Superfund site—the largest in the nation. The ensuing struggle to identify the scope of PCB contamination, compel GE to take responsibility, and decide on corrective measures lasted for 25 years. Eventually, government agencies directed GE to dredge and remove PCB-contaminated sediment from 40 areas known as “hot spots” in a 40-mile stretch of the Upper Hudson.

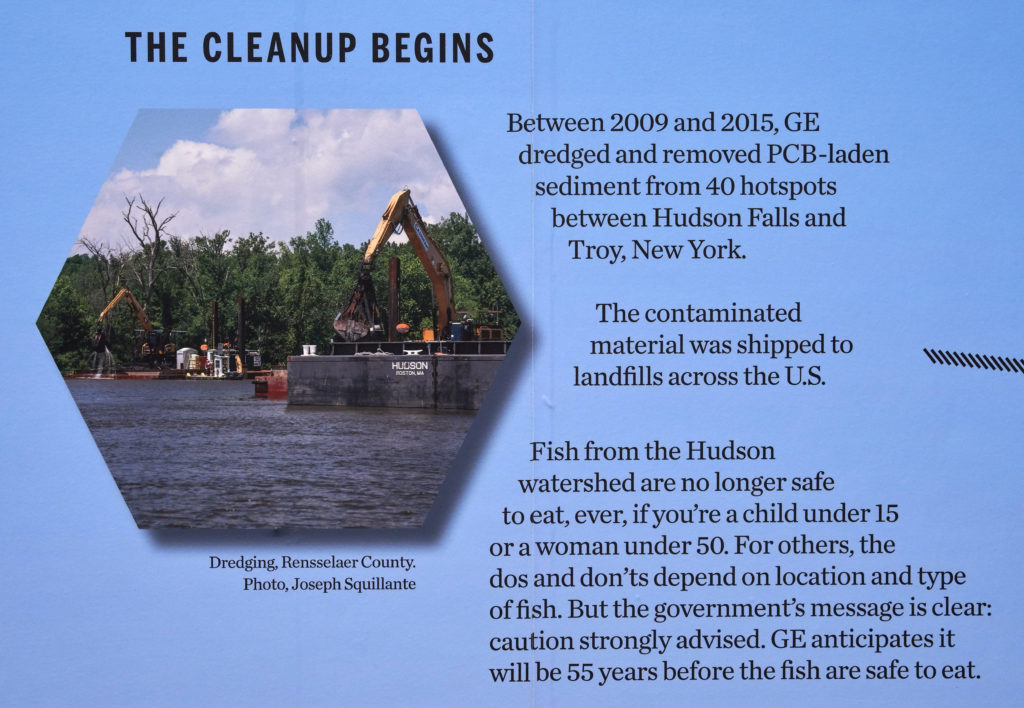

The Cleanup Begins

Between 2009 and 2015, GE dredged and removed PCB-laden sediment from 40 hot spots between Hudson Falls and Troy, New York. The contaminated material was shipped to landfills across the United States.

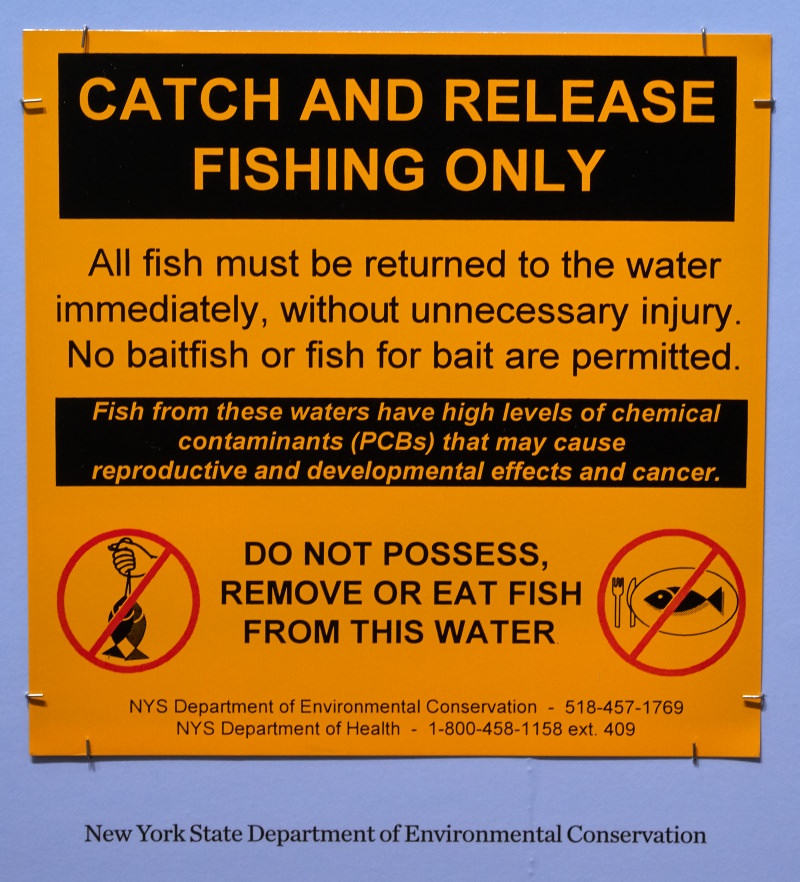

Fish from the Hudson watershed are no longer safe to eat, ever, if you’re a child under 15 or a woman under 50. For others, the dos and don’ts depend on location and type of fish. But the government’s message is clear: caution strongly advised. GE anticipates it will be 55 years before the fish are safe to eat.

The Cleanup Continues

Today, GE is monitoring the impact of the dredging and conducting mandated testing in Upper Hudson floodplains to check for contamination on land.

GE says they’ve done enough. Environmental groups and the responsible government agencies disagree—their viewpoint was bolstered by a 2014 Albany Times Union investigation using internal GE documents. Tests of river water have shown far more contamination than previously believed. PCBs continue to leak into the water from difficult-to-reach deposits. In December 2018, Governor Cuomo and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation released a new study showing continuing, harmful PCB contamination.

Restoring Resiliency

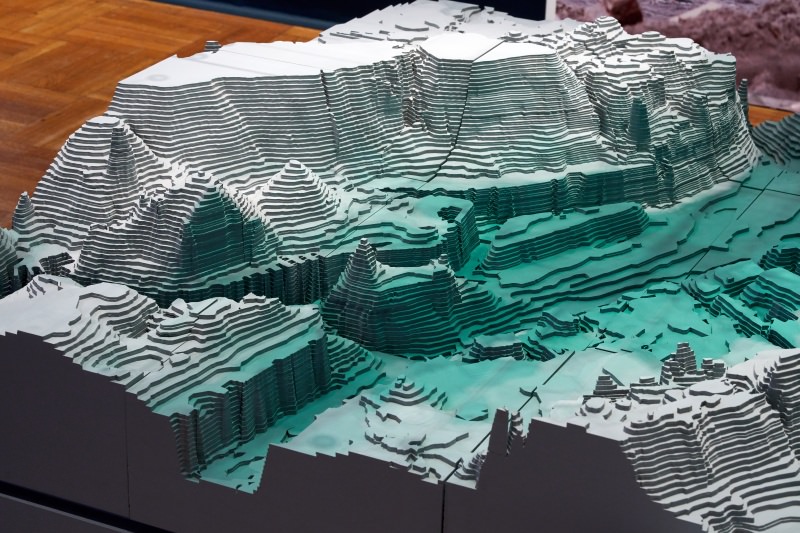

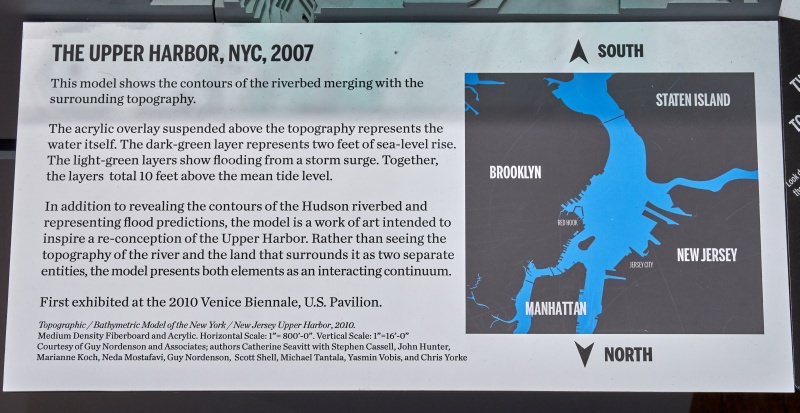

Two centuries of engineering and development have left waterfront areas vulnerable to extreme storms and rising seas. Now shorelines are being re-engineered to restore nature’s own protections.

Climate Change along the Hudson

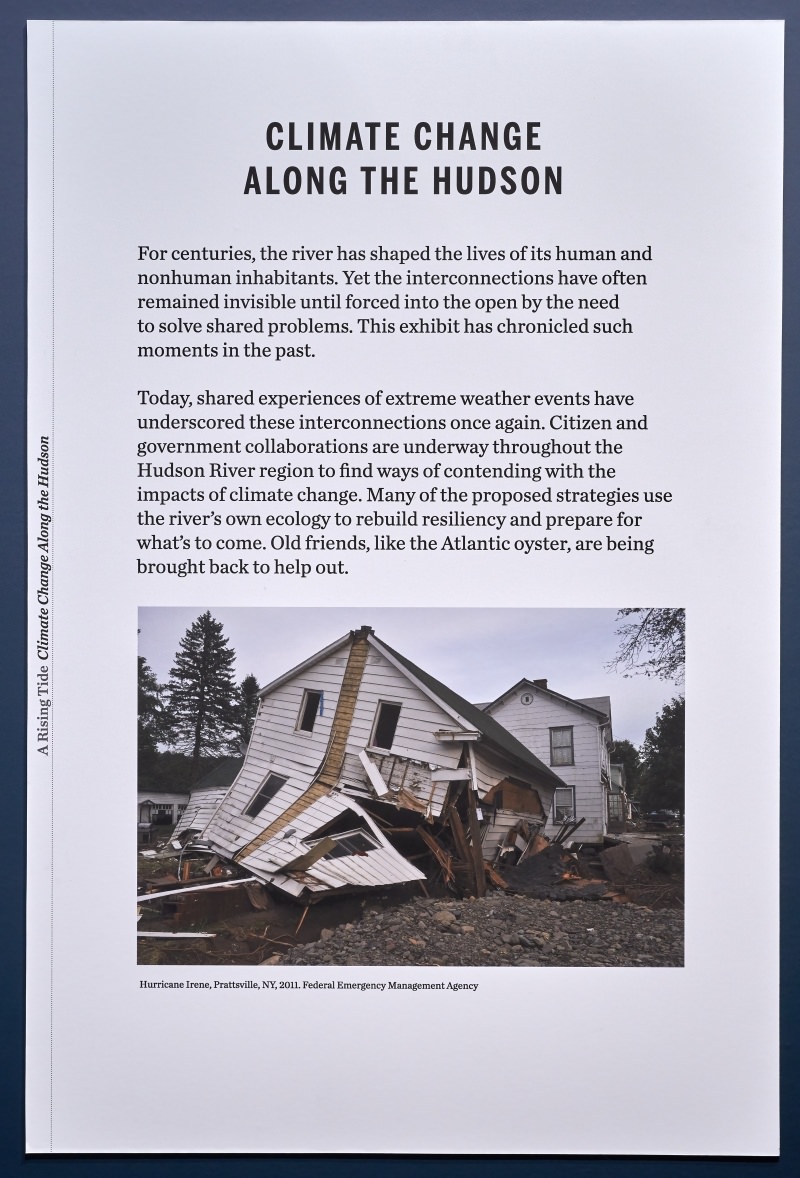

For centuries, the river has shaped the lives of its human and nonhuman inhabitants. Yet the interconnections have often remained invisible until forced into the open by the need to solve shared problems. This exhibit has chronicled such moments in the past.

Today, shared experiences of extreme weather events have underscored these interconnections once again. Citizen and government collaborations are underway throughout the Hudson River region to find ways of contending with the impacts of climate change. Many of the proposed strategies use the river’s own ecology to rebuild resiliency and prepare for what’s to come. Old friends, like the Atlantic oyster, are being brought back to help out.

To learn about a river plan that will guide the next decade of restoration along the Hudson, see the “Hudson River Comprehensive Restoration Plan.” The plan was released in 2018 by Partners Restoring the Hudson, a group of more than 30 organizations convened by The Nature Conservancy and dedicated to protecting the river. www.thehudsonweshare.org

Generous support for this exhibition provided by First Republic Bank, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Lily Auchincloss Foundation, William T. Morris Foundation, Inc., Shaiza Rizavi and Jonathan Friedland, The Hart Charitable Trust, and Dr. Charlotte K. Frank in memory of Pete Seeger.

Exhibitions at New-York Historical are made possible by Dr. Agnes Hsu-Tang and Oscar Tang, the Saunders Trust for American History, the Seymour Neuman Endowed Fund, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. WNET is the media sponsor.