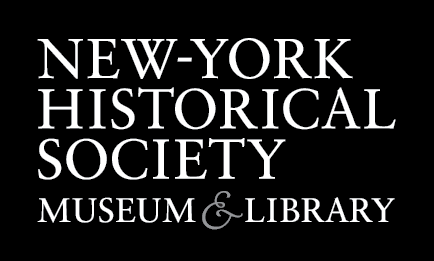

The Hudson Highlands: 1960s–1980s

A sudden narrowing of the river and the rise of steep mountains on both its sides, from Haverstraw Bay to Newburgh Bay, signal the Hudson Highlands. No stretch of the Hudson has earned more praise for its beauty and history. Few campaigns to save the environment have had greater impact than the one conducted in the Highlands.

By the early 1960s, power plants were rising along the Hudson to support the region’s booming economy and sprawling population. When Consolidated Edison announced plans to build a plant on Storm King Mountain, citizen activists drew the line. They fought the plant for 17 years, in the end preventing its construction. New legal tools for protecting the environment emerged from their campaign.

Meanwhile, all along the Hudson, ecological awareness was growing. Citizens and government officials began challenging the status quo around pollution. The Hudson had become a cesspool.

By the 1980s, dramatic change had occurred. Citizens could legally intervene to stop projects that put treasured natural resources at risk. New laws regulated the ability to pollute and the handling of raw sewage. Organizations to protect the environment sprang up along the Hudson and throughout the country.

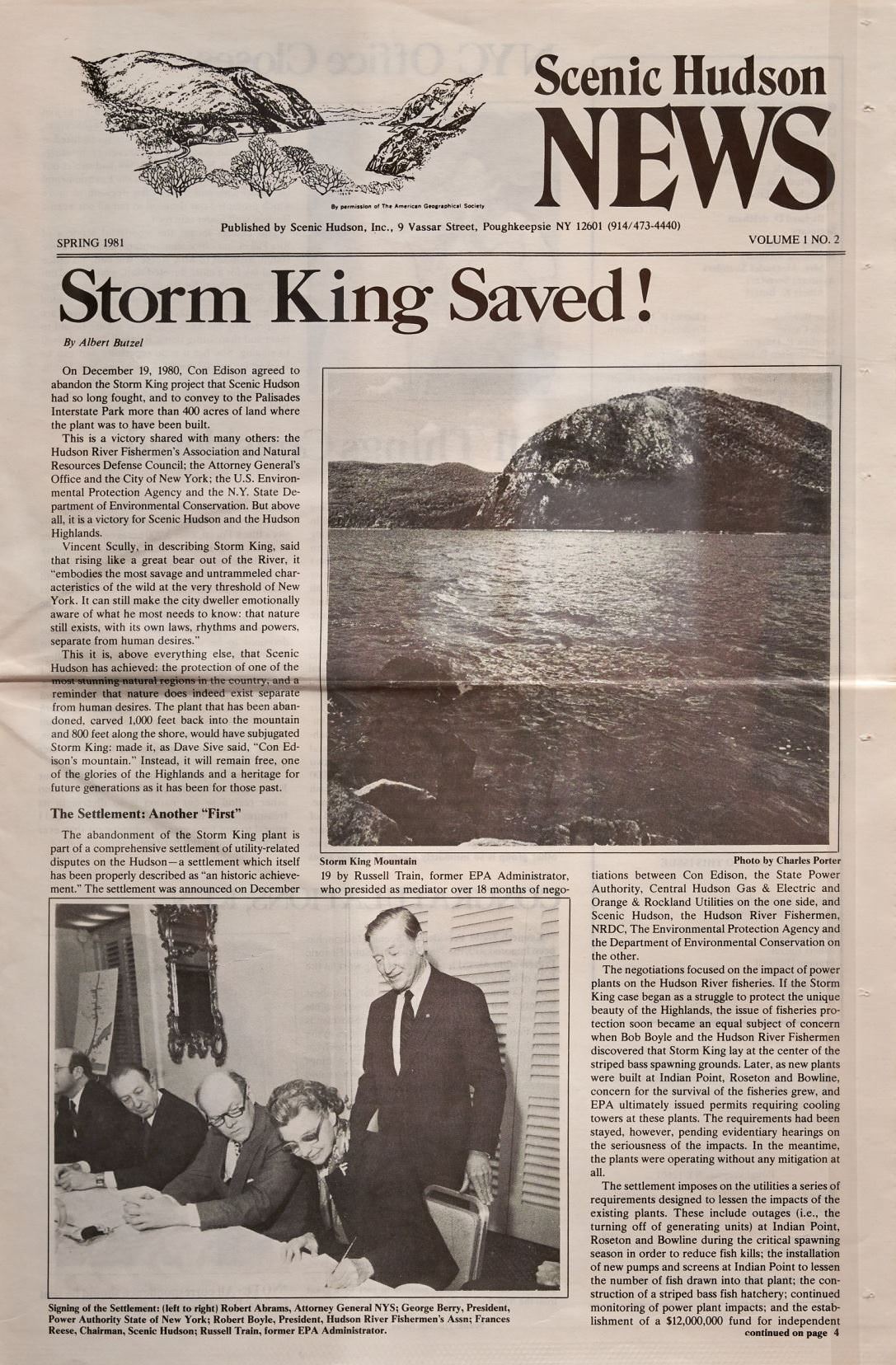

The Storm King Controversy

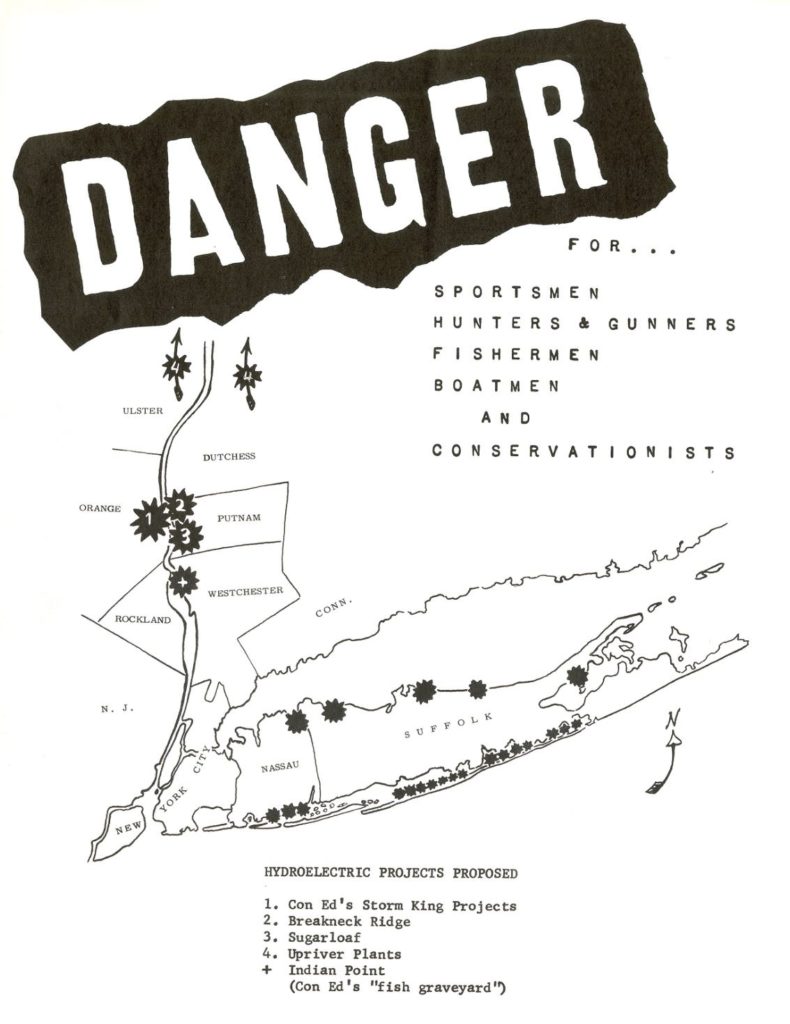

In September 1962, Con Edison announced plans to build a hydroelectric plant on Storm King Mountain. Opposition soon emerged from fishermen, environmental activists, and local residents on both sides of the river. These opponents formed coalitions and fought Con Edison in the courts of law and public opinion for the next 17 years.

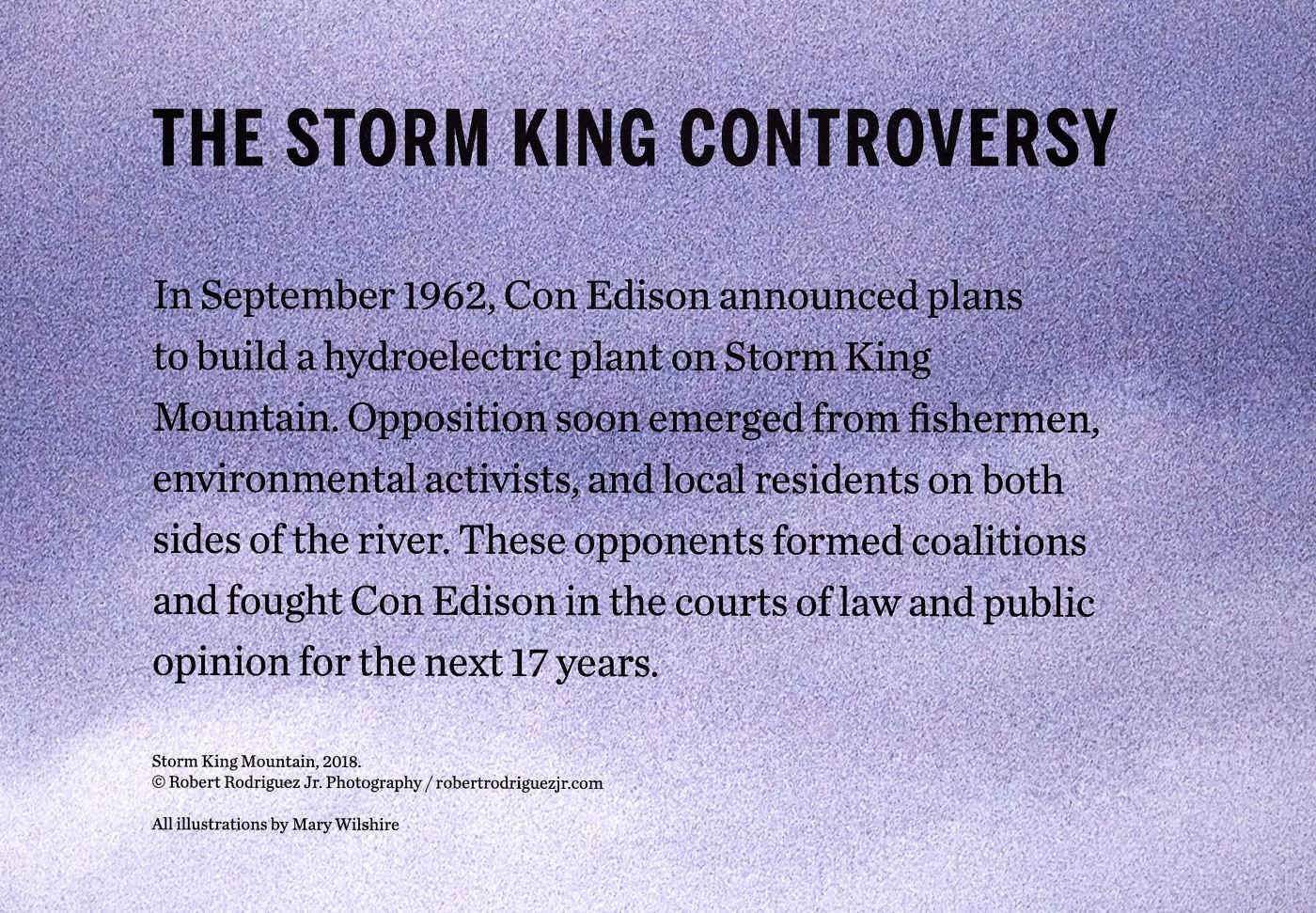

Con Edison Proposes a Hydroelectric Plant

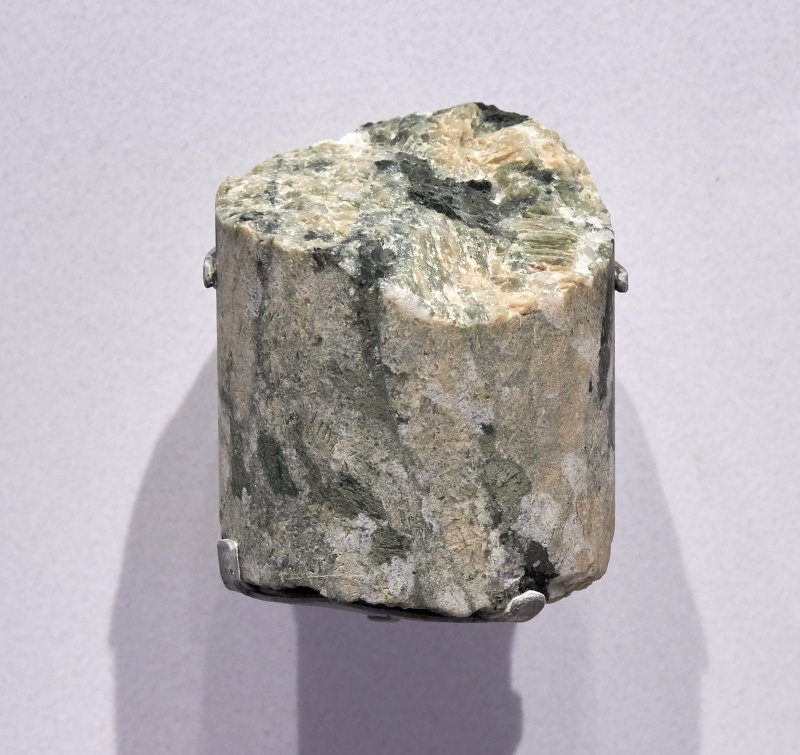

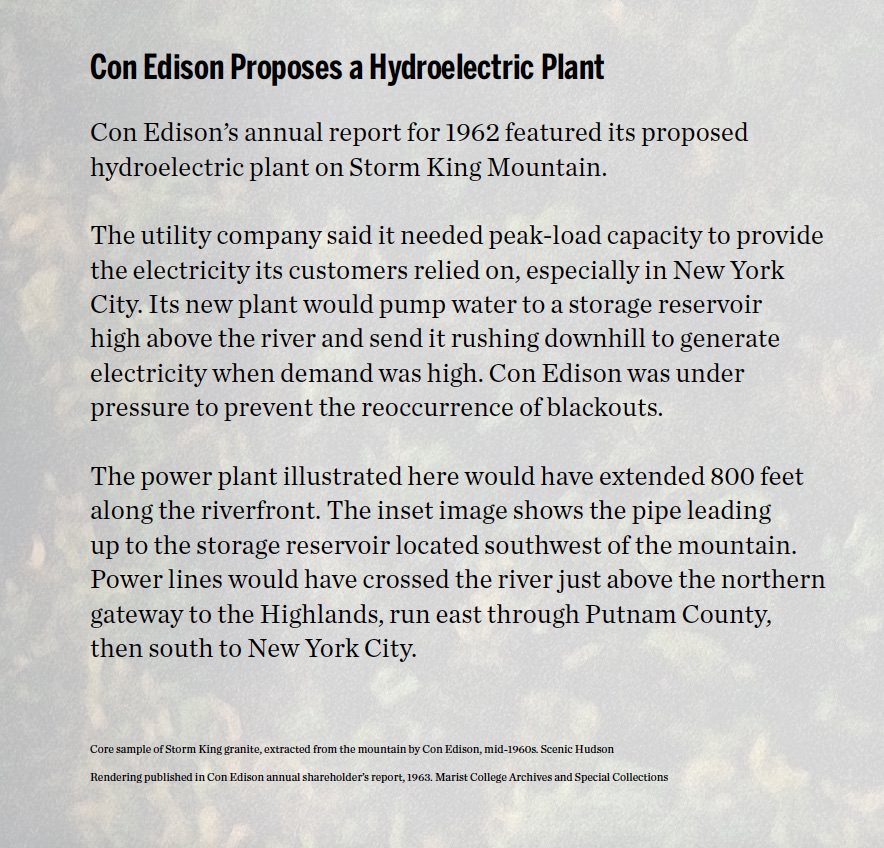

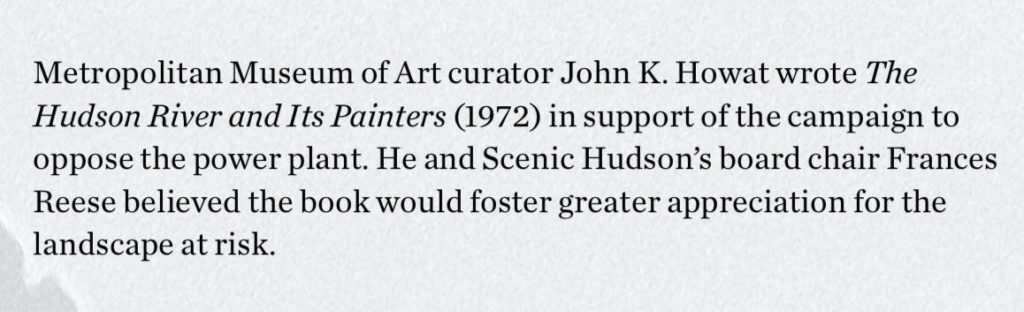

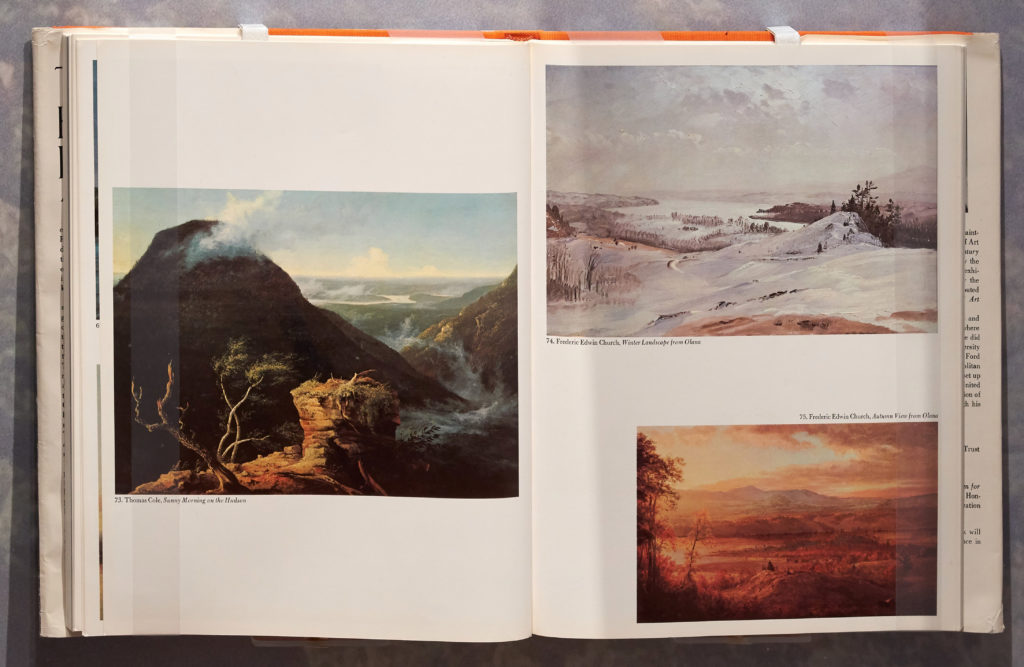

Con Edison’s annual report for 1962 featured its proposed hydroelectric plant on Storm King Mountain.

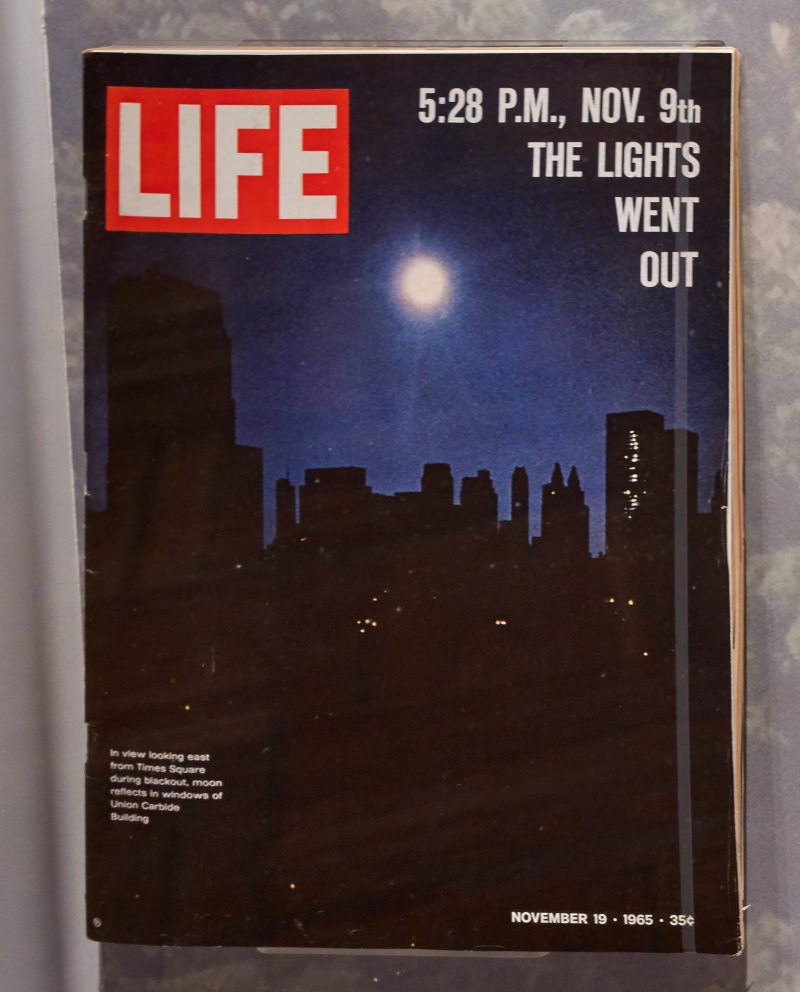

The utility company said it needed peak-load capacity to provide the electricity its customers relied on, especially in New York City. Its new plant would pump water to a storage reservoir high above the river and send it rushing downhill to generate electricity when demand was high. Con Edison was under pressure to prevent the reoccurrence of blackouts.

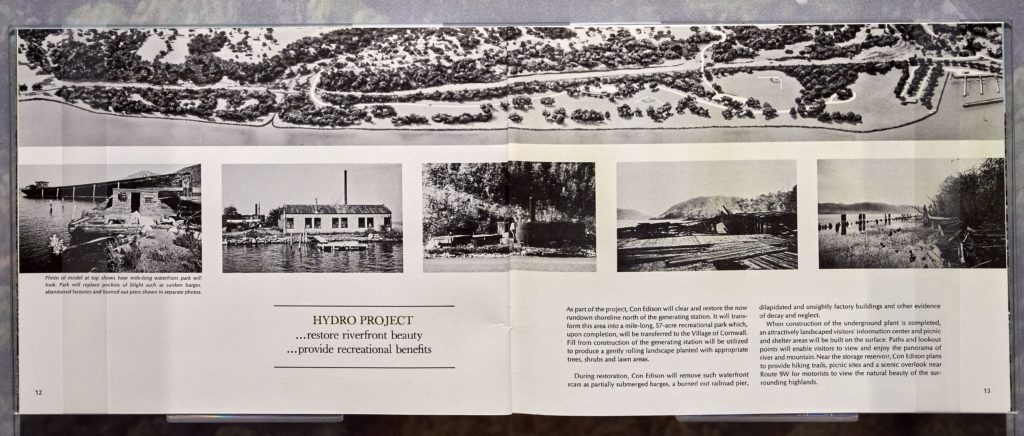

The power plant illustrated here would have extended 800 feet along the riverfront. The inset image shows the pipe leading up to the storage reservoir located southwest of the mountain. Power lines would have crossed the river just above the northern gateway to the Highlands, run east through Putnam County, then south to New York City.

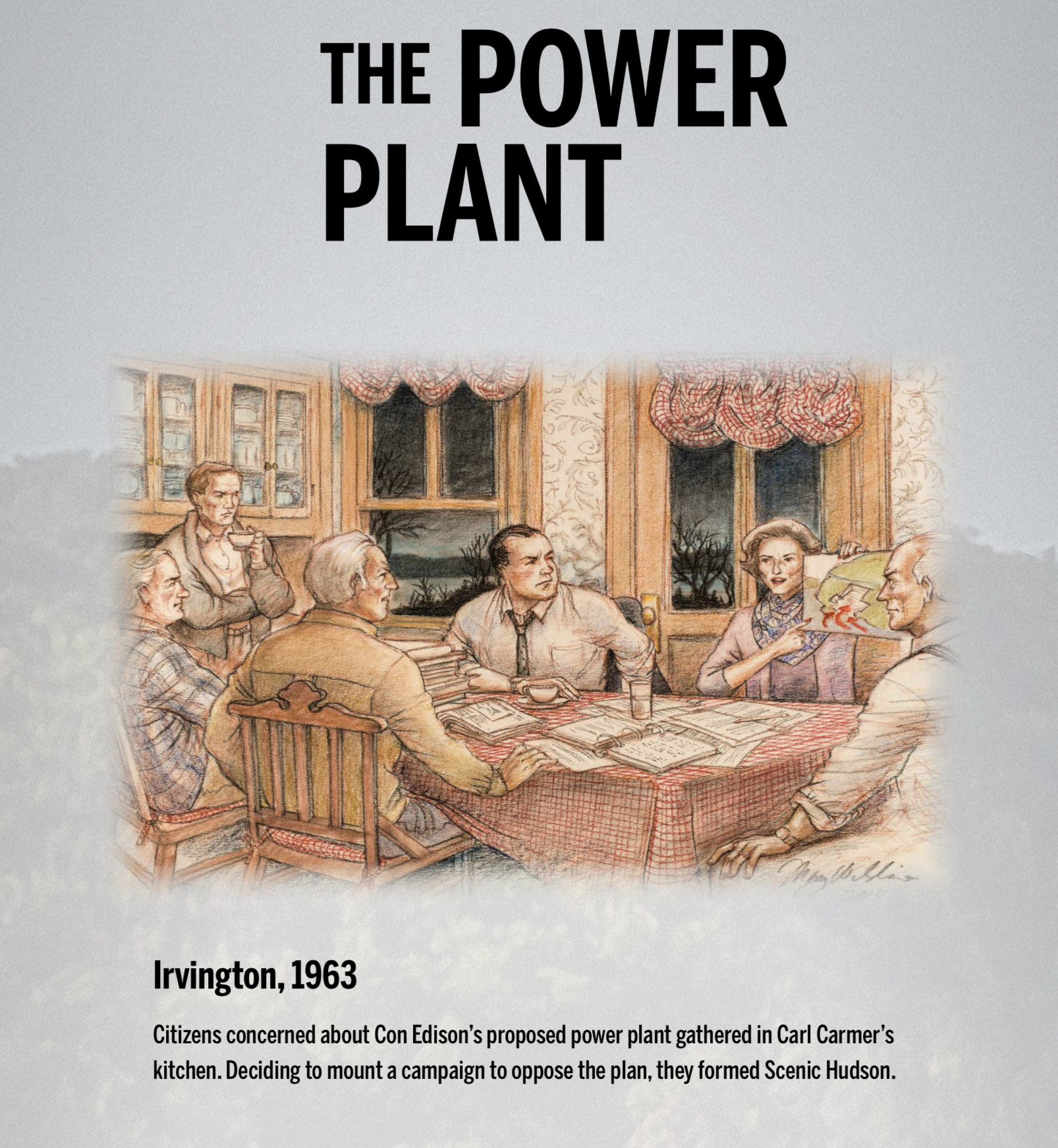

Citizens Mobilize Against the Plant

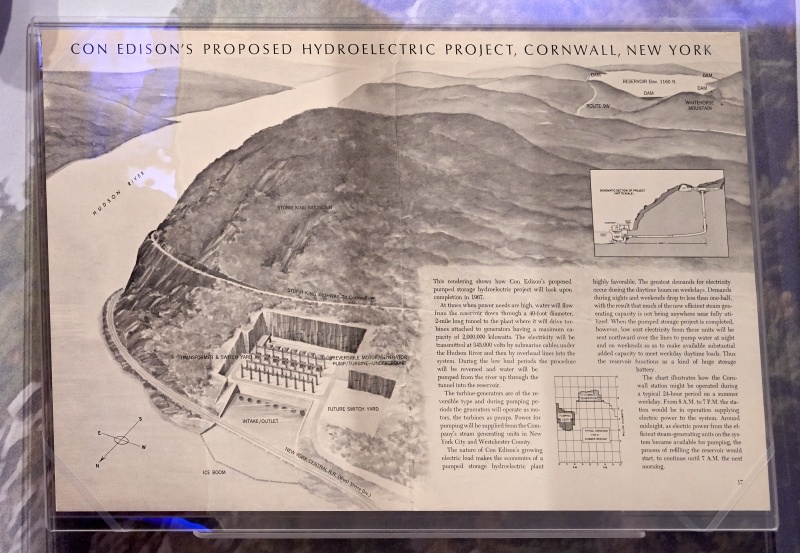

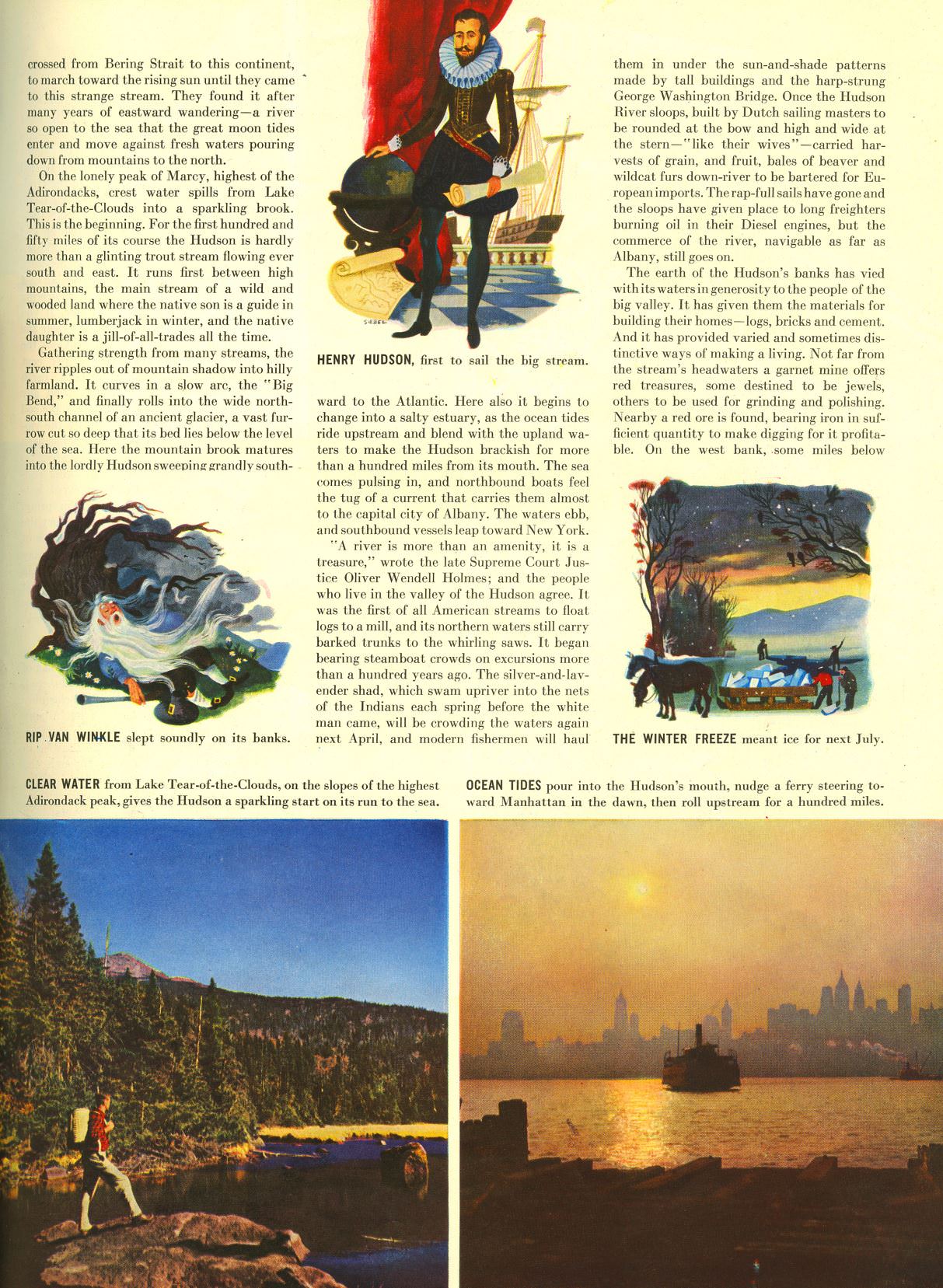

Author Carl Carmer had been writing about New York City’s history and lore for decades before cofounding the campaign against Con Edison’s power plant. “A river is more than an amenity,” he wrote here, quoting former Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. “It is a treasure.”

To Carmer and the Hudson Valley residents who gathered with him in 1963, Con Edison’s annual report showed what was wrong with its plan. This massive plant was sitting astride majestic Storm King Mountain, along the river’s most beautiful stretch. The group formed the Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference to oppose the power plant.

The plant’s opponents first drew attention to Storm King’s beauty, history, and recreational offerings. Once fishermen joined in, the river’s habitat and ecology became an important focus.

Pro and Con Arguments

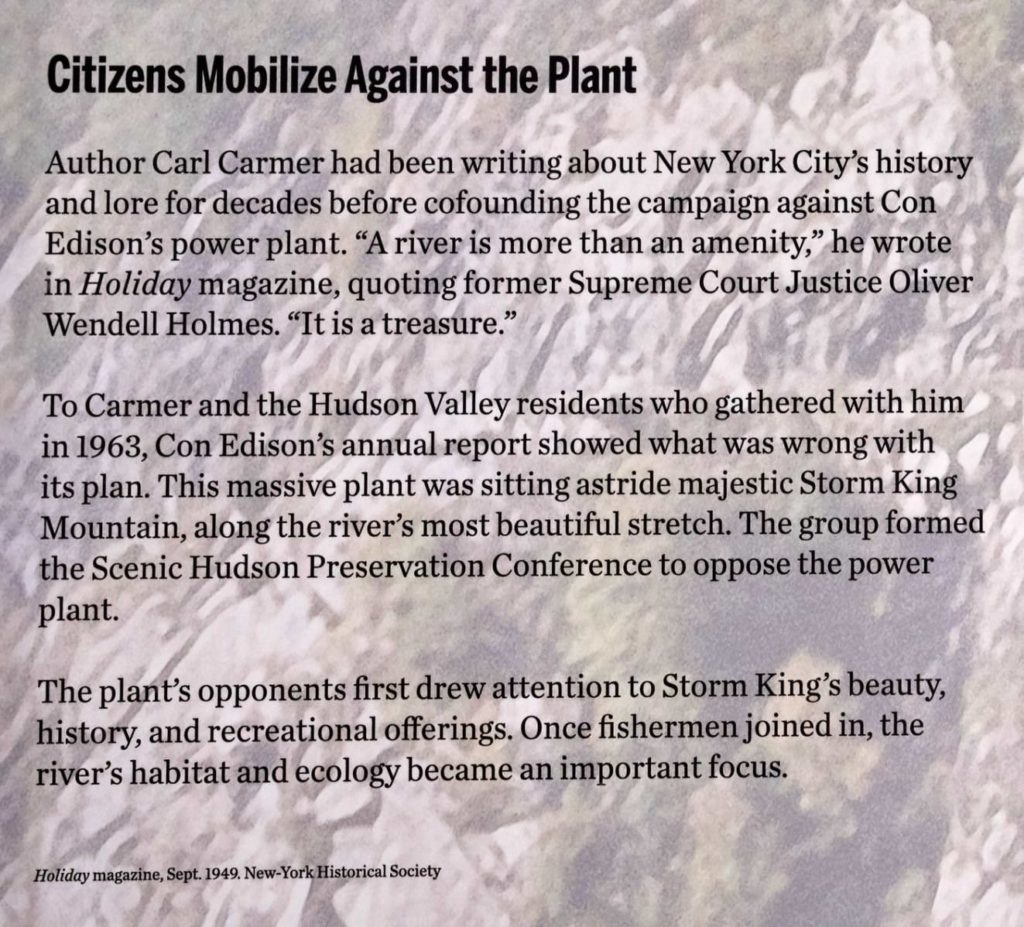

In July 1964, Con Edison’s plant received preliminary approval from the Federal Power Commission (FPC). That November, New York’s Joint Legislative Committee on Natural Resources held a public hearing at Bear Mountain Inn where they heard pro and con arguments from the public. Dutchess County Republican R. Watson Pomeroy presided.

Supporters of the power plant lauded Con Edison for promising to make aesthetic improvements to an already highly industrialized riverfront landscape. Opponents argued that the Storm King plant would further destroy what remained of the Hudson’s natural beauty and historic places.

Speakers for the opposition also stated that the river’s fish and fisheries were at mortal risk. The sport fisherman and journalist Bob Boyle had reported in Sports Illustrated that Con Edison’s Indian Point nuclear power plant was already killing millions of Hudson River fish. He testified at the hearing that Con Edison had not told the FPC that crucial striped bass spawning grounds lay adjacent to Storm King Mountain.

The legislators voted 5-0 to oppose the Storm King plant, but early the next year, the FPC granted Con Edison a license to build it.

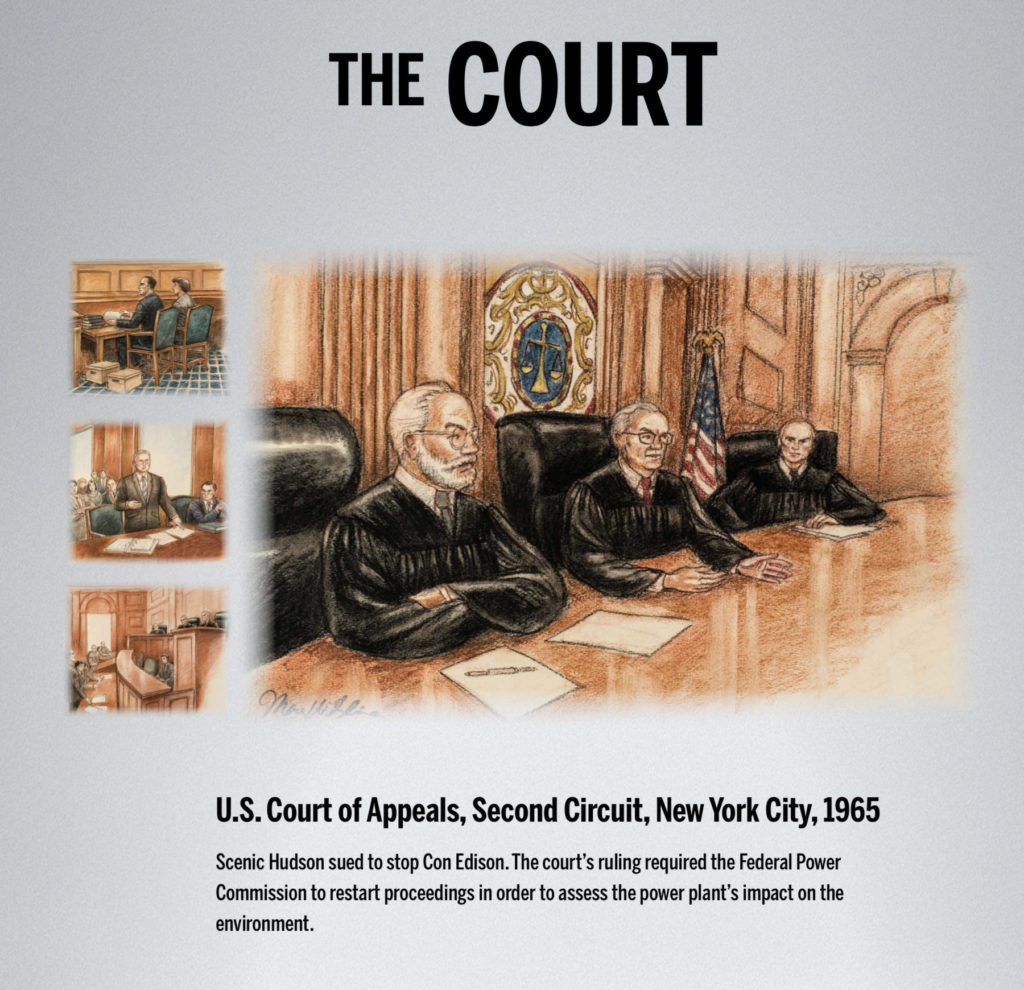

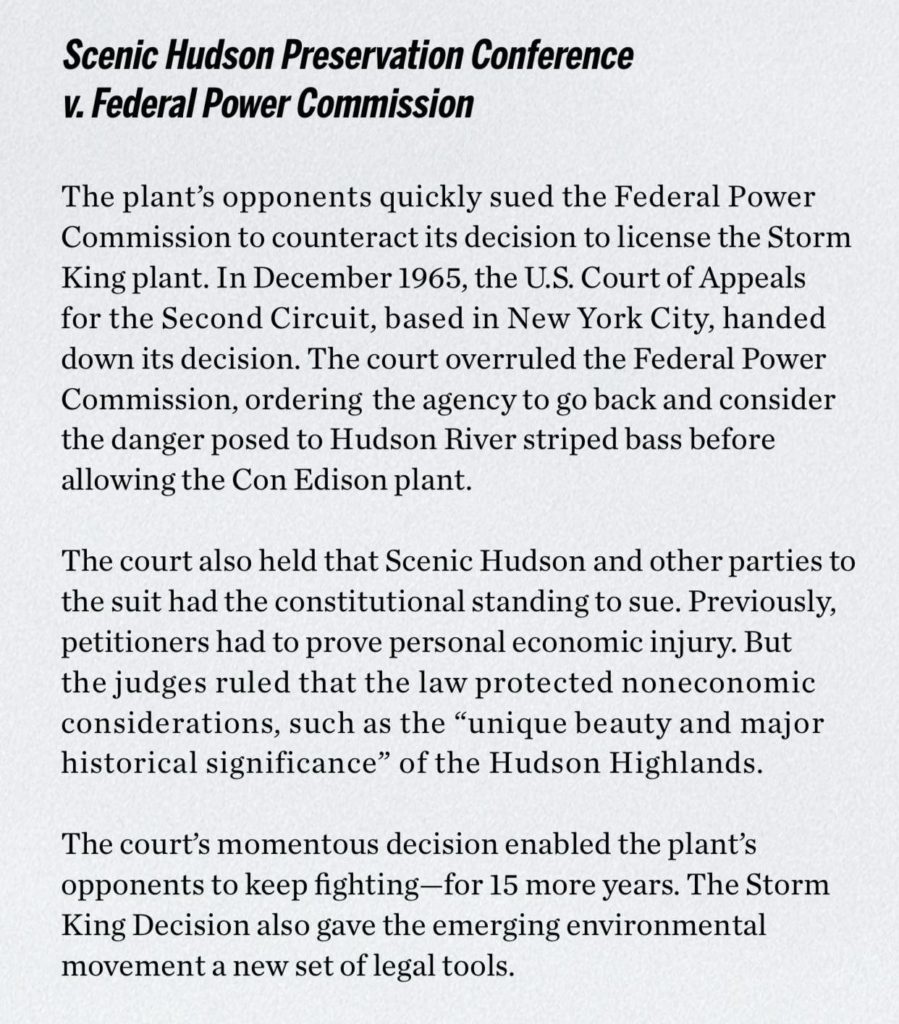

Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission

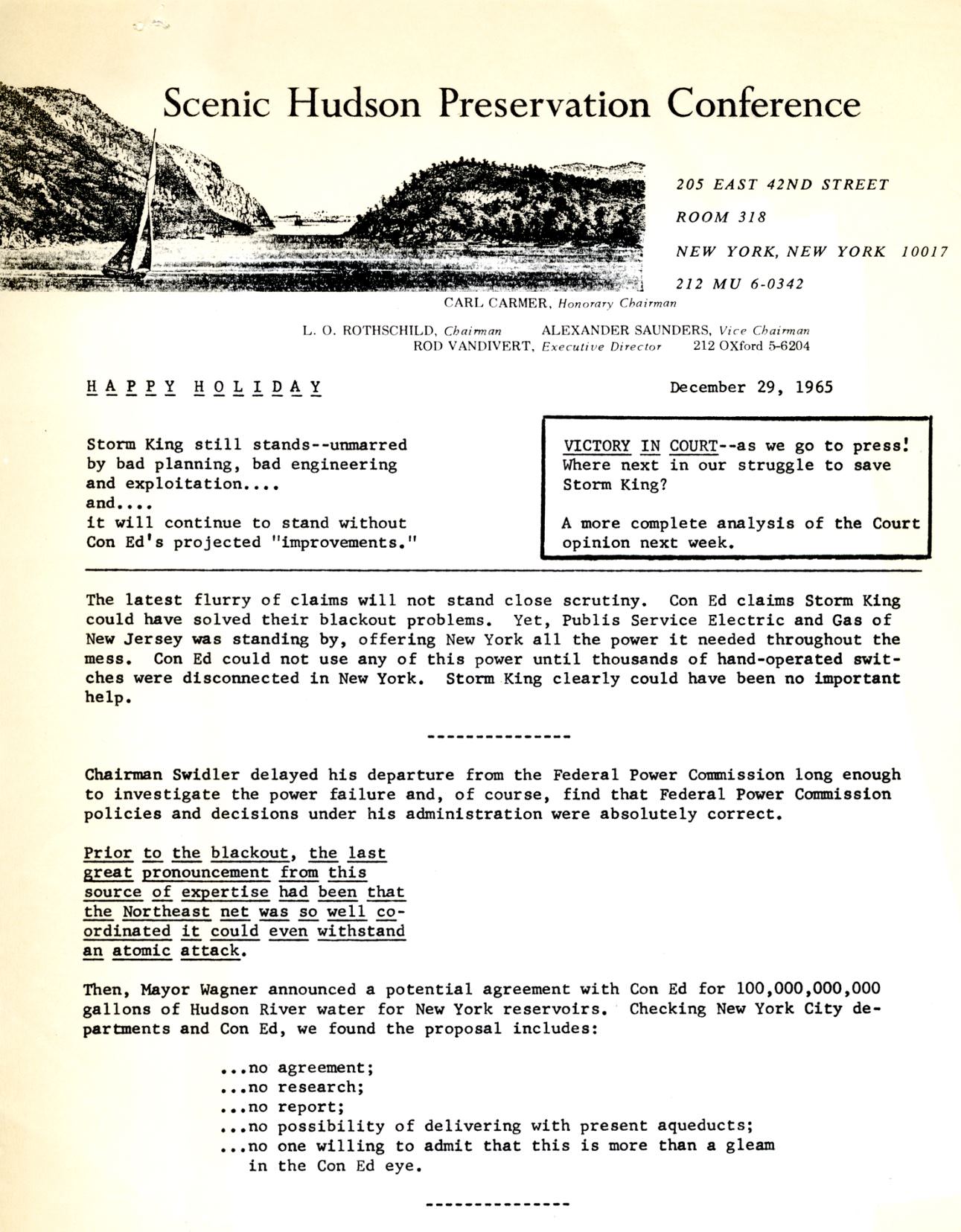

The plant’s opponents quickly sued the Federal Power Commission to counteract its decision to license the Storm King plant. In December 1965, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, based in New York City, handed down its decision. The court reversed the Federal Power Commission’s ruling, ordering the agency to go back and consider the danger posed to Hudson River striped bass before allowing the Con Edison plant.

The court also held that Scenic Hudson and other parties to the suit had the constitutional standing to sue. Previously, petitioners had to prove personal economic injury. But the judges ruled that the law protected noneconomic considerations, such as the “unique beauty and major historical significance” of the Hudson Highlands.

The court’s momentous decision enabled the plant’s opponents to keep fighting—for 15 more years. The Storm King Decision also gave the emerging environmental movement a new set of legal tools.

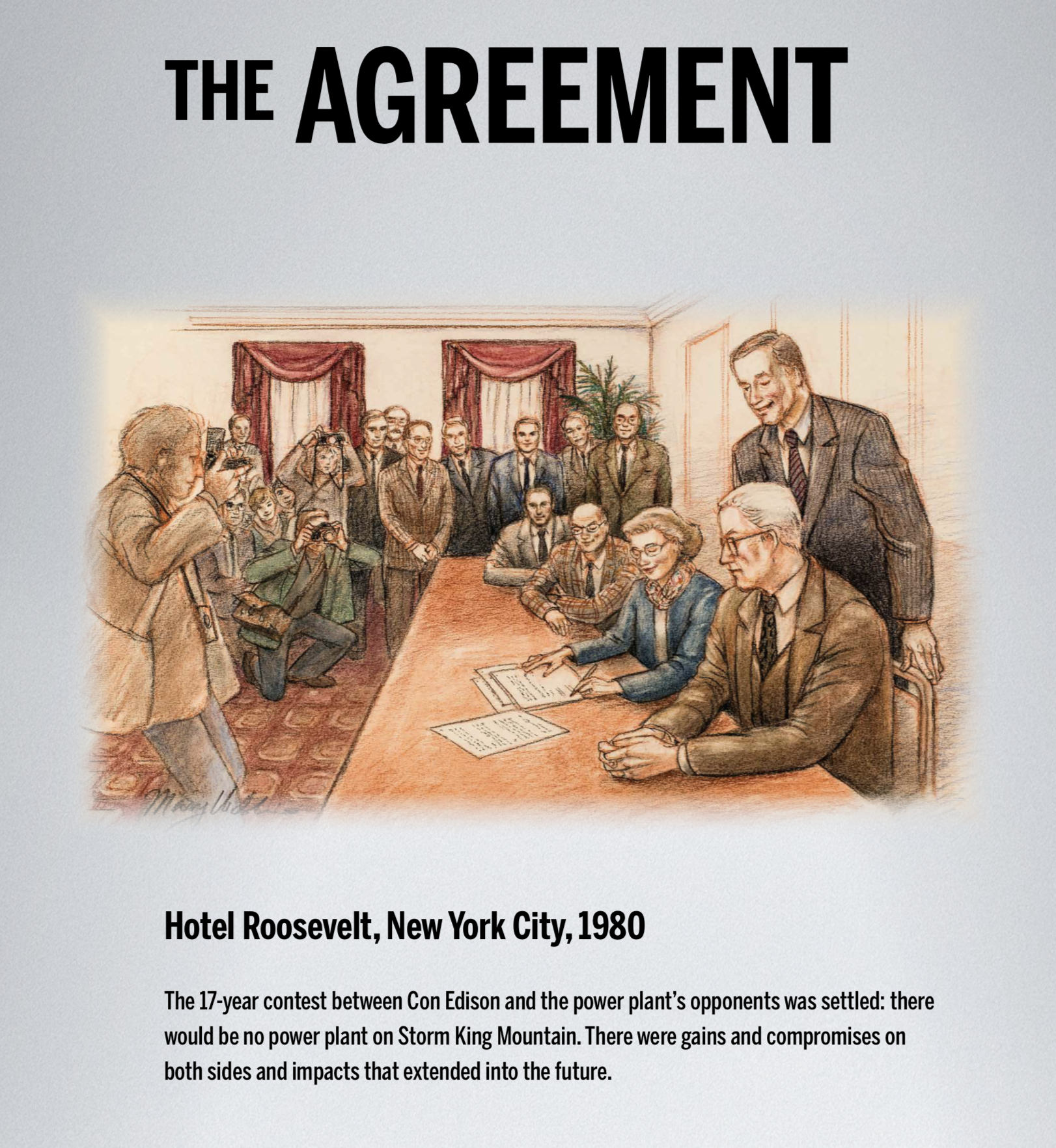

The Hudson River Peace Treaty

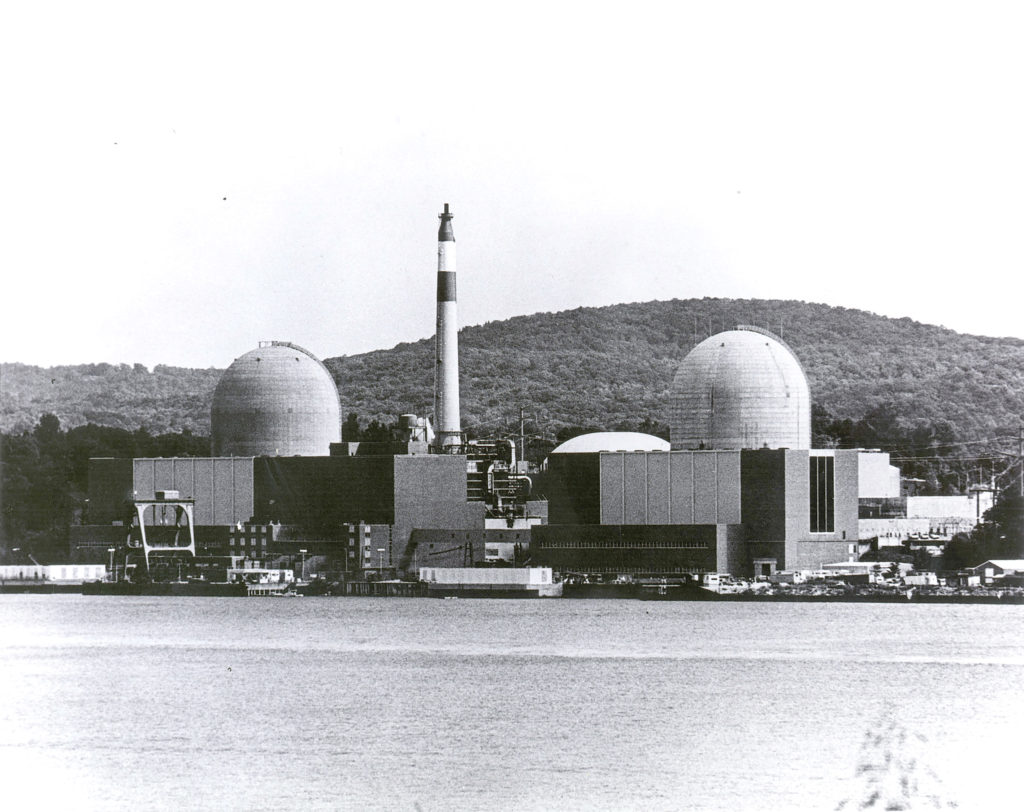

Finally, in 1980, the contest over Con Edison’s Storm King plant was settled. The parties compromised. Con Edison surrendered its Federal Power Commission license and donated the land it had assembled to the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. The utility agreed to modify its nearby Indian Point nuclear power plant to reduce fish kills, and to take the plant off-line during striped bass spawning season. Con Edison also established a $12 million endowment for ecological research on the Hudson.

Frances Reese, chairwoman of Scenic Hudson, and Bob Boyle, of the Fishermen’s Association, signed the agreement with Con Edison and government officials.

In return, the agreement stipulated that Con Edison would not have to build enormous and expensive cooling towers at the Indian Point nuclear power plant. The towers had been mandated by the Environmental Protection Agency in order to prevent the fish from being sucked into the giant water cooling system.

Legacy of the Storm King Contest

What resulted from the Storm King struggle? Citizens around the country now had standing to sue in court on behalf of environmental concerns. Federal agencies were now required to investigate all relevant facts before granting approvals. The scenic, historic, and recreational character of places could now be protected under the law.

Plus, important environmental organizations had been born. Scenic Hudson, the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association (now Riverkeeper), Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, and the Natural Resources Defense Council changed the nature of environmental stewardship in the Hudson region and beyond. And using the settlement funds received from Con Edison, the Hudson River Foundation began the first-ever sustained research on the complex ecology of the Hudson.

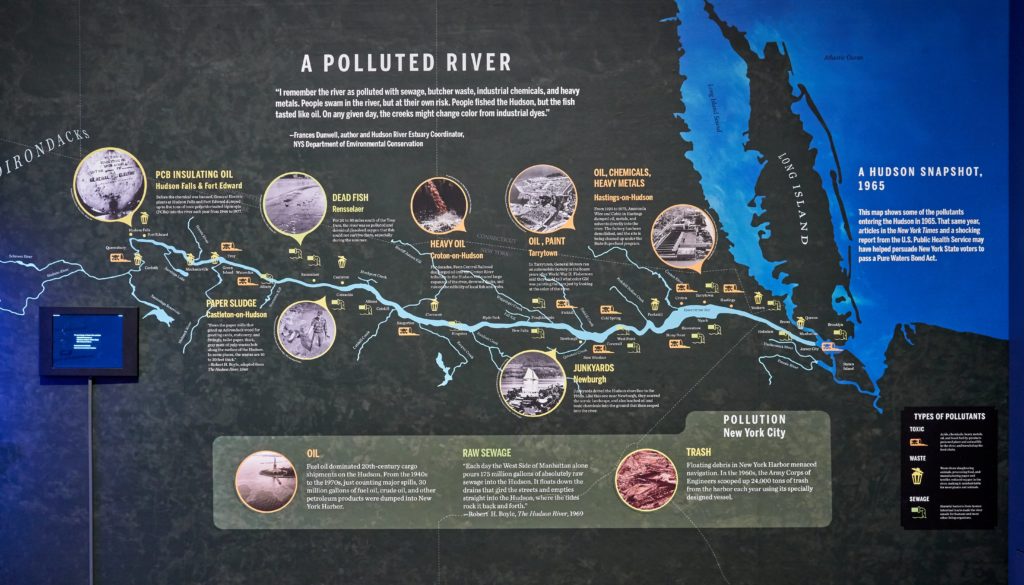

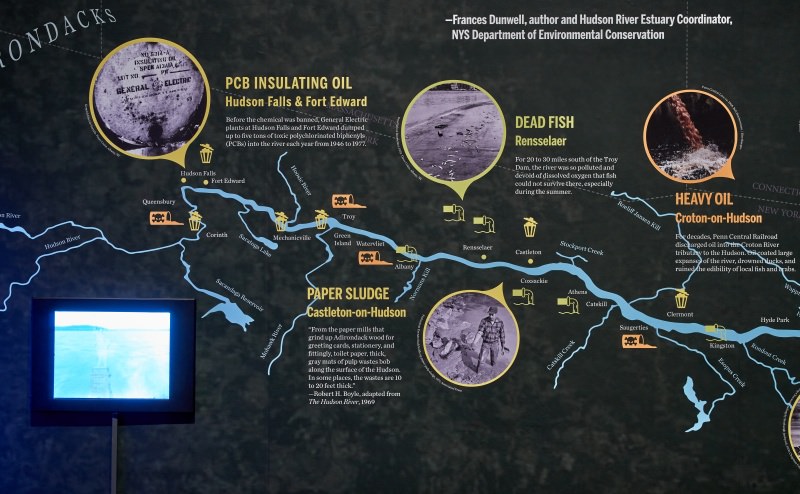

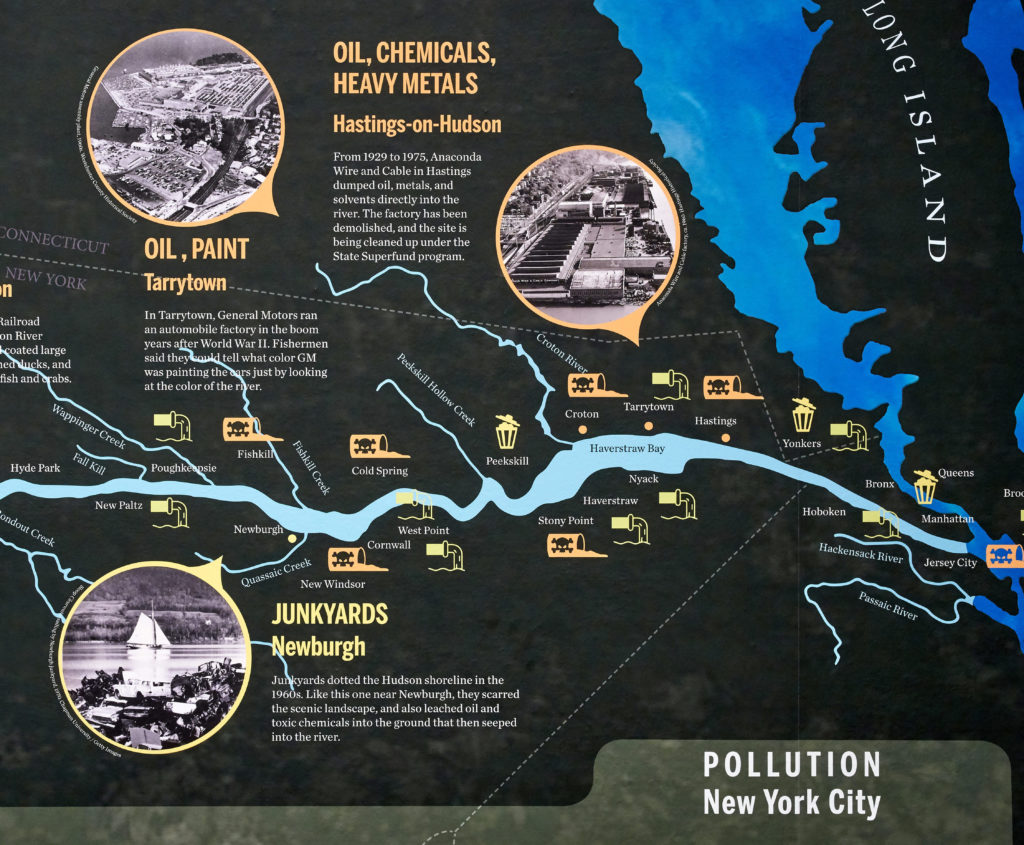

A Hudson Snapshot, 1965

This map shows some of the pollutants entering the Hudson in 1965. That same year, articles in the New York Times and a shocking report from the U.S. Public Health Service may have helped persuade New York State voters to pass a Pure Waters Bond Act.

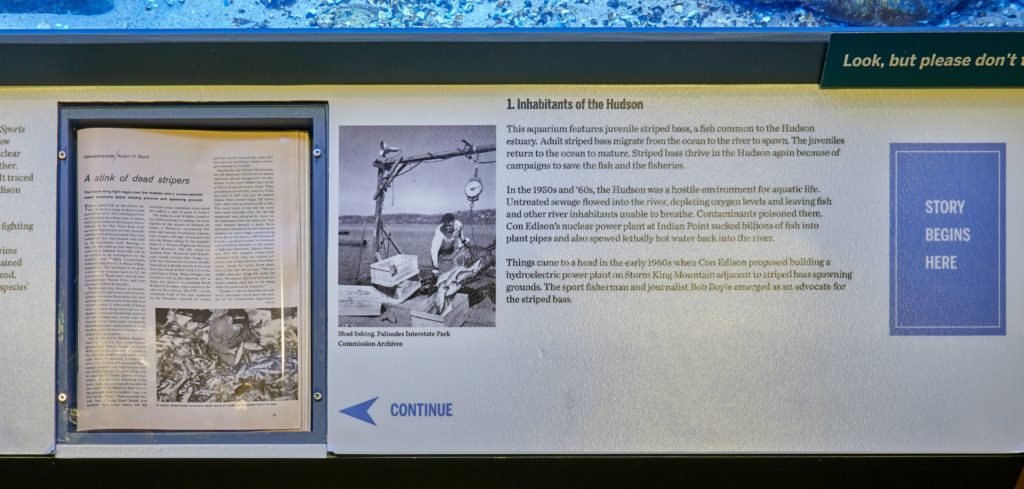

Inhabitants of the Hudson

This aquarium features juvenile striped bass, a fish common to the Hudson estuary. Adult striped bass migrate from the ocean to the river to spawn. The juveniles return to the ocean to mature. Striped bass thrive in the Hudson again because of campaigns to save the fish and the fisheries.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the Hudson was a hostile environment for aquatic life. Untreated sewage flowed into the river, depleting oxygen levels and leaving fish and other river inhabitants unable to breathe. Contaminants poisoned them. Con Edison’s nuclear power plant at Indian Point sucked billions of fish into plant pipes and also spewed lethally hot water back into the river.

Things came to a head in the early 1960s when Con Edison proposed building a hydroelectric power plant on Storm King Mountain, adjacent to striped bass spawning grounds. The sport fisherman and journalist Bob Boyle emerged as an advocate for the striped bass.

Bob Boyle

Bob Boyle was a recreational fly fisherman who wrote for Sports Illustrated. When he and other Hudson River fishermen saw evidence of massive, daily fish kills at the Indian Point nuclear power plant in Westchester County, they investigated further. In 1965, Boyle published this article in Sports Illustrated. It traced the problem to the plant’s operations, and charged Con Edison and government officials with orchestrating a cover-up.

Boyle shared his concerns with Scenic Hudson, the group fighting another Con Edison power plant proposed for Storm King Mountain, in Cornwall, New York. Storm King sat next to prime spawning grounds for Atlantic coast striped bass. Boyle explained that the impact of two plants would be doubly lethal. In the end, the likelihood that the Storm King plant might threaten the species’ survival played a role in defeating Con Edison’s proposal.

The Hudson River Fishermen’s Association

In 1966, commercial and recreational fishermen gathered around Bob Boyle’s aquarium and formed a new organization. They would be aided by two nearly forgotten laws. The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1888 and the Refuse Act of 1899 forbade pollution of American waters and provided cash bounties for those who reported violations. The new Hudson River Fishermen’s Association used these laws to save the Hudson’s fish.

The group’s first bounty of $2,000 was collected from Penn Central Railroad. Bounties from other polluters followed, including Standard Brands, Ciba-Geigy, Westchester County, and Anaconda Wire and Cable.

Beginning in 1972, the Fishermen’s Association began a“Riverkeeper” program to patrol the river. Ten years later, Riverkeeper John Cronin and his boat were monitoring the river full-time. In 1986, the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association merged with its Riverkeeper program to form one group to protect the river.