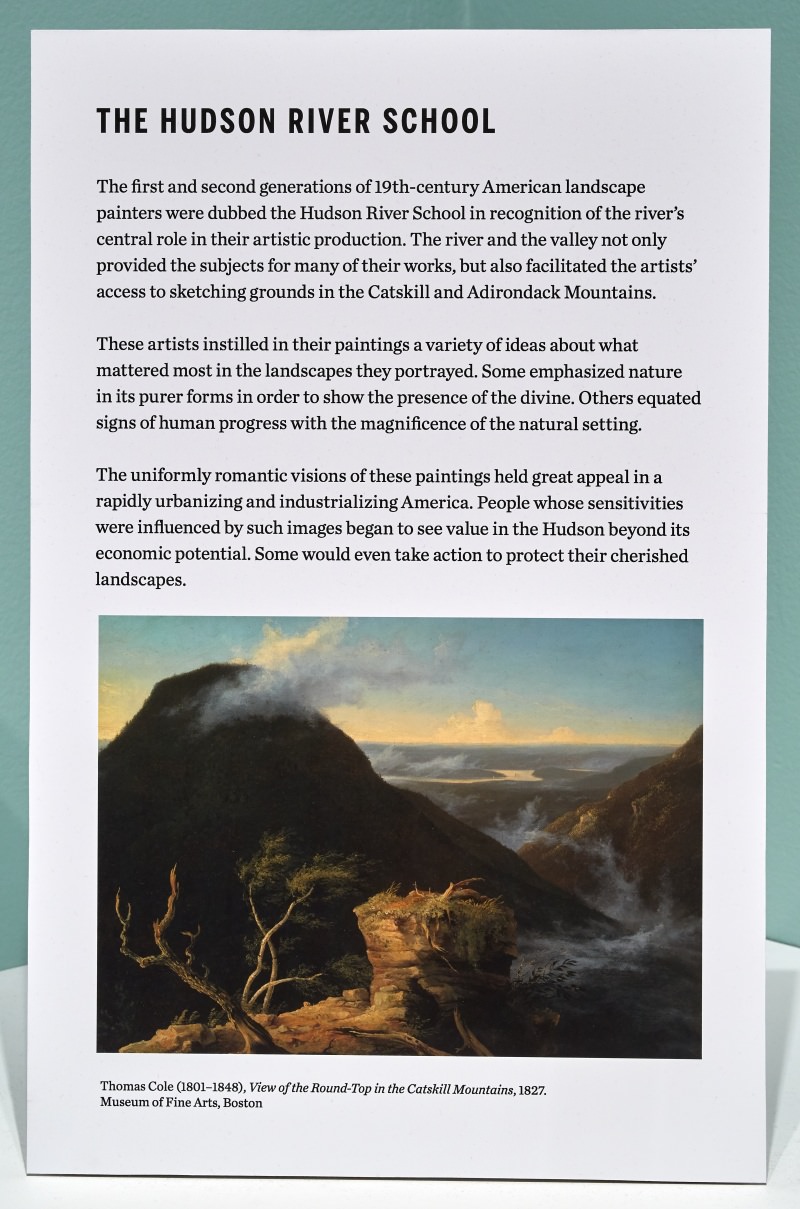

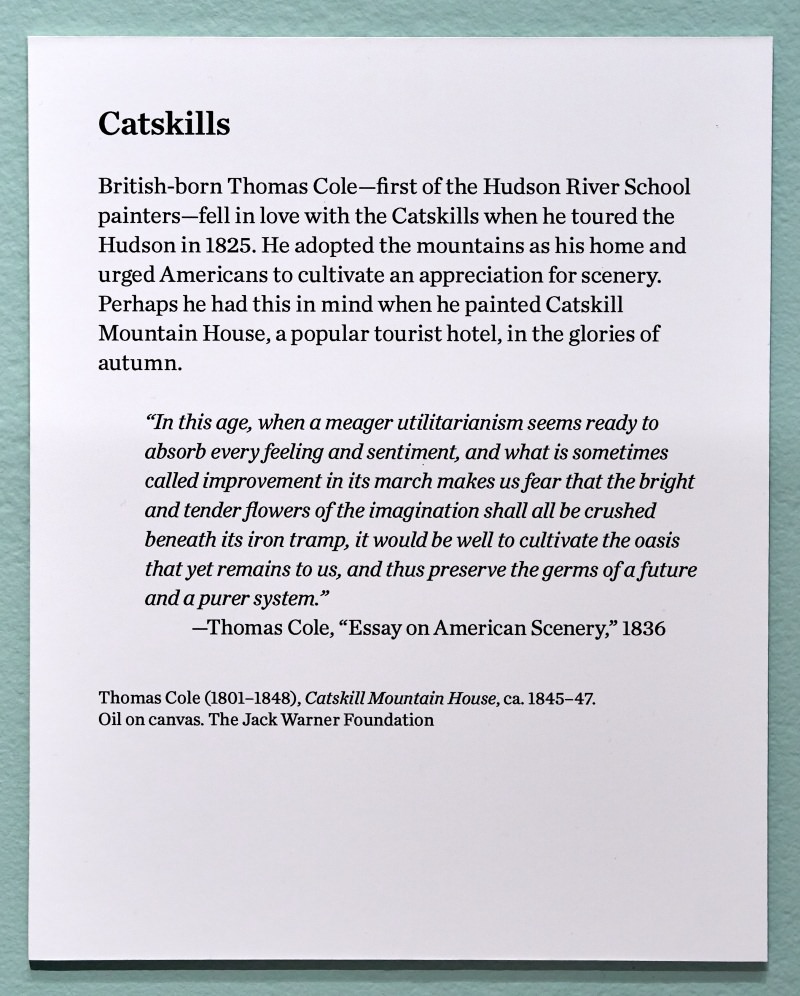

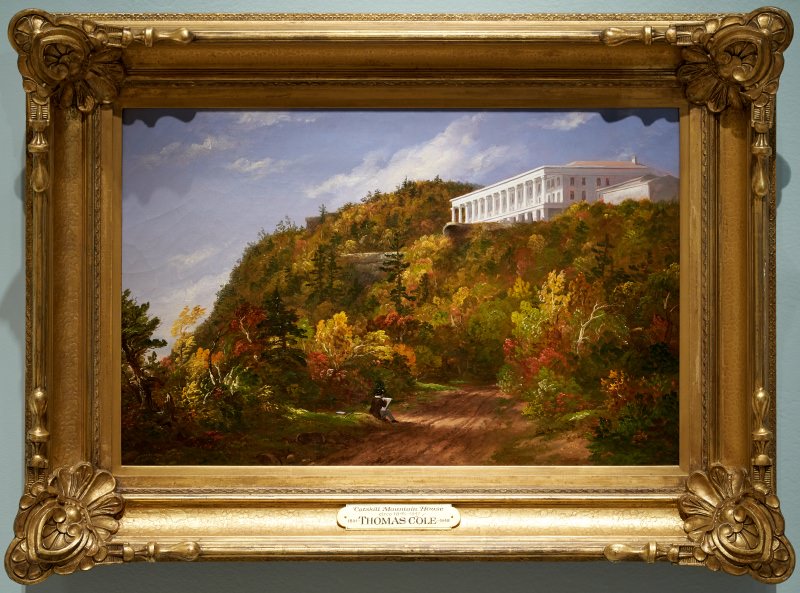

The Hudson River School

The first and second generations of 19th-century American landscape painters were dubbed the Hudson River School in recognition of the river’s central role in their artistic production. The river and the valley not only provided the subjects for many of their works, but also facilitated the artists’ access to sketching grounds in the Catskill and Adirondack Mountains.

These artists instilled in their paintings a variety of ideas about what mattered most in the landscapes they portrayed. Some emphasized nature in its purer forms in order to show the presence of the divine. Others equated signs of human progress with the magnificence of the natural setting.

The uniformly romantic visions of these paintings held great appeal in a rapidly urbanizing and industrializing America. People whose sensitivities were influenced by such images began to see value in the Hudson beyond its economic potential. Some would even take action to protect their cherished landscapes.

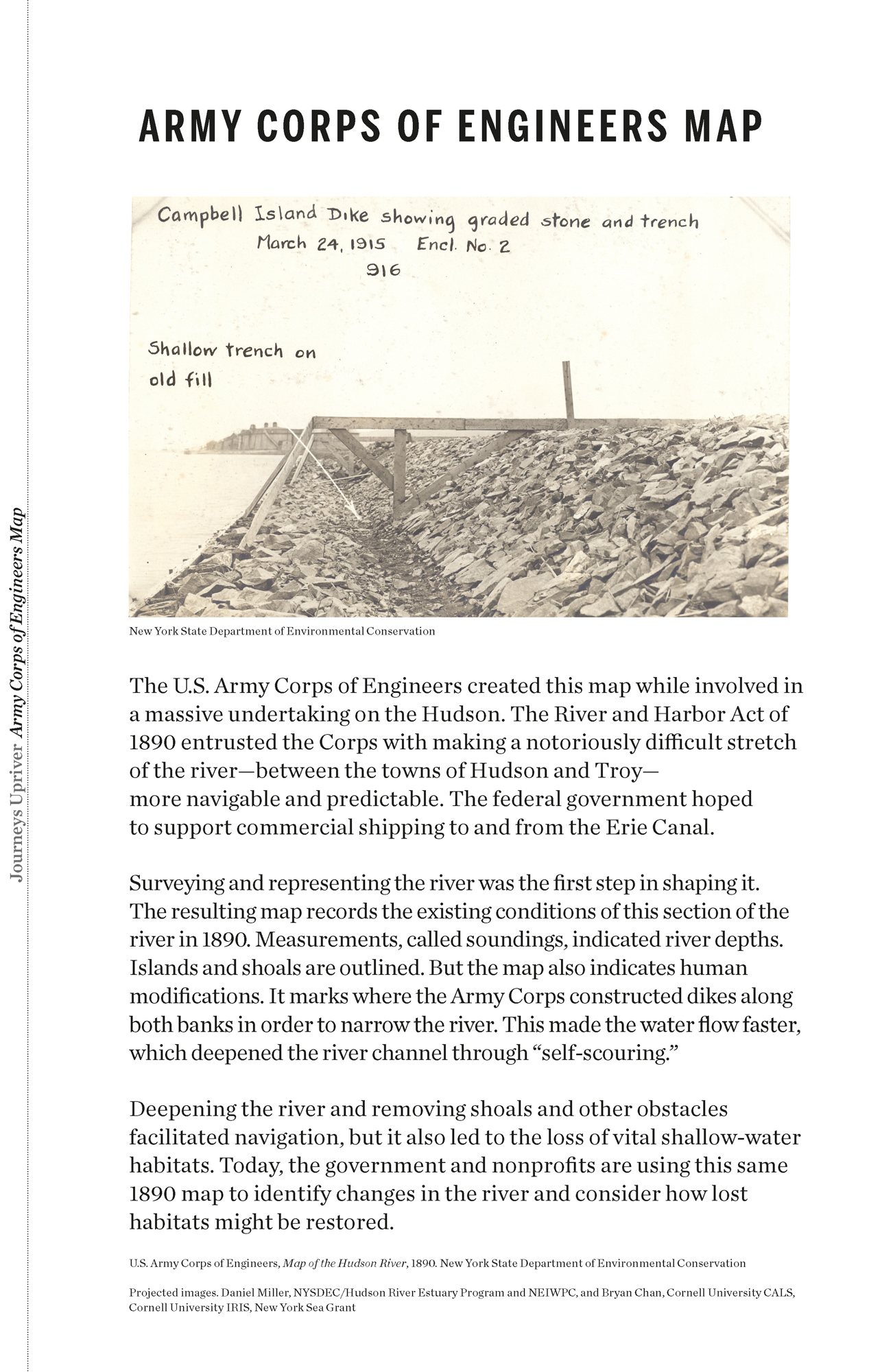

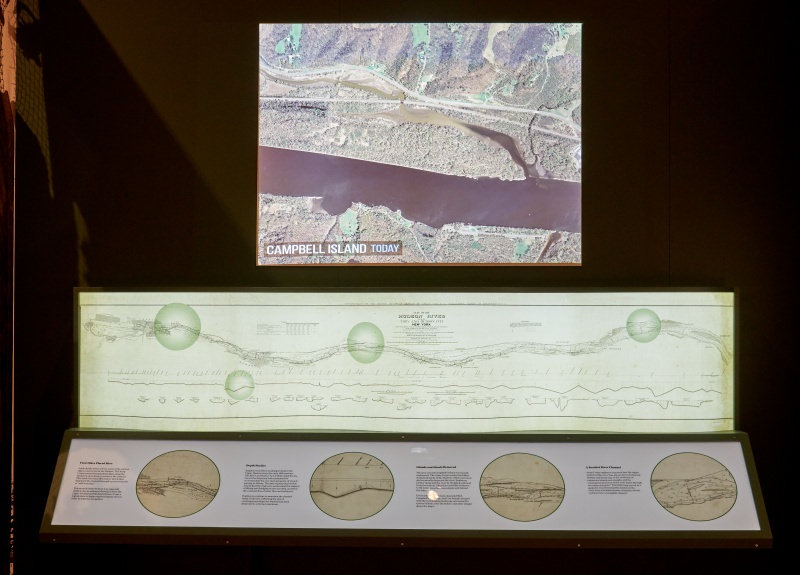

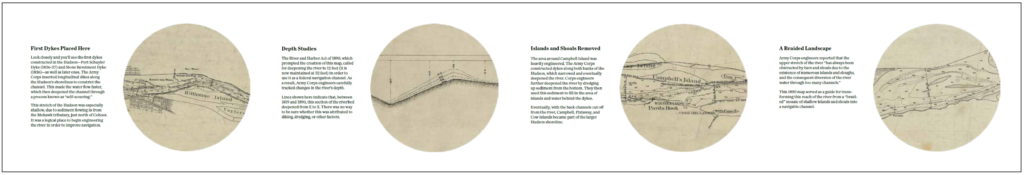

Army Corps of Engineers Map

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers created this map while involved in a massive undertaking on the Hudson. The River and Harbor Act of 1890 entrusted the Corps with making a notoriously difficult stretch of the river—between the towns of Hudson and Troy—more navigable and predictable. The federal government hoped to support commercial shipping to and from the Erie Canal.

Surveying and representing the river was the first step in shaping it. The resulting map records the existing conditions of this section of the river in 1890. Measurements, called soundings, indicated river depths. Islands and shoals are outlined. But the map also indicates human modifications. It marks where the Army Corps constructed dikes along both banks in order to narrow the river. This made the water flow faster, which deepened the river channel through “self-scouring.”

Deepening the river and removing shoals and other obstacles facilitated navigation, but it also led to the loss of vital shallow-water habitats. Today, the government and nonprofits are using this same 1890 map to identify changes in the river and consider how lost habitats might be restored.