The Palisades: 1890s–1950s

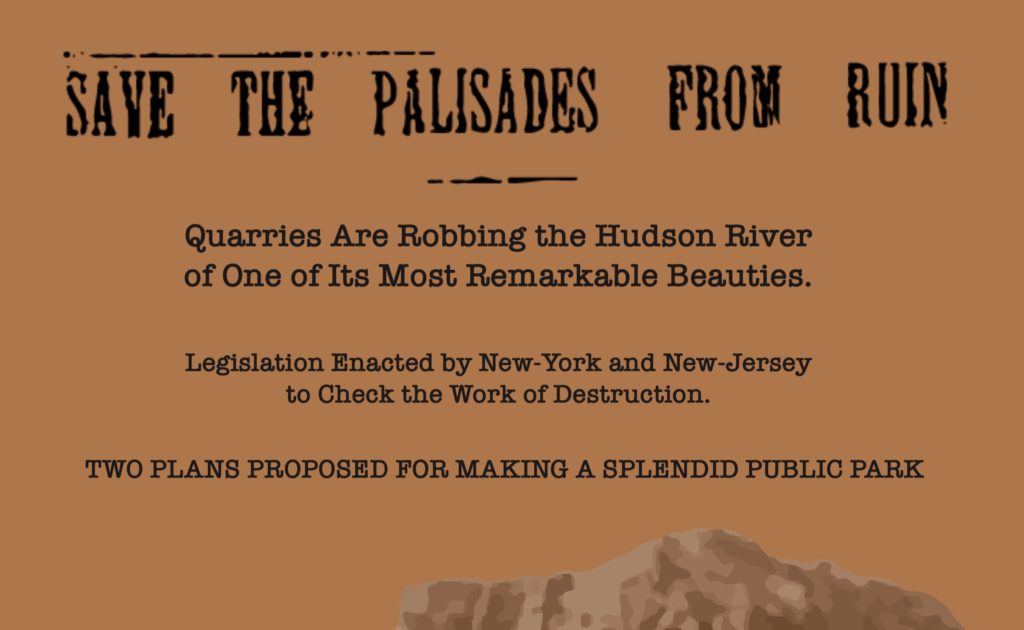

The ancient cliffs of the Palisades line the west side of the Hudson in New Jersey and New York. While the natural beauty of the cliffs has been extolled for centuries, in the 1800s, builders of docks and roads prized rock from the Palisades. By the 1890s, the builders were blasting the forested cliffs to bits.

Such massive destruction spurred a struggle for the future of the Palisades. In the end, the opponents of the blasting won. They acquired the land and put the cliffs under the protection of an innovative interstate commission.

In 1909, Palisades Interstate Park emerged. The park preserved the magnificent sight of the cliffs and provided a place for city dwellers to experience nature firsthand.

Previously, it had been artists and writers who recognized and most powerfully expressed the experience of the Hudson and its surroundings. With the creation of a park in the Palisades, a government agency now set the stage for millions of ordinary Americans to create their own experiences. The result was a heightened awareness of nature and growing support for conservation.

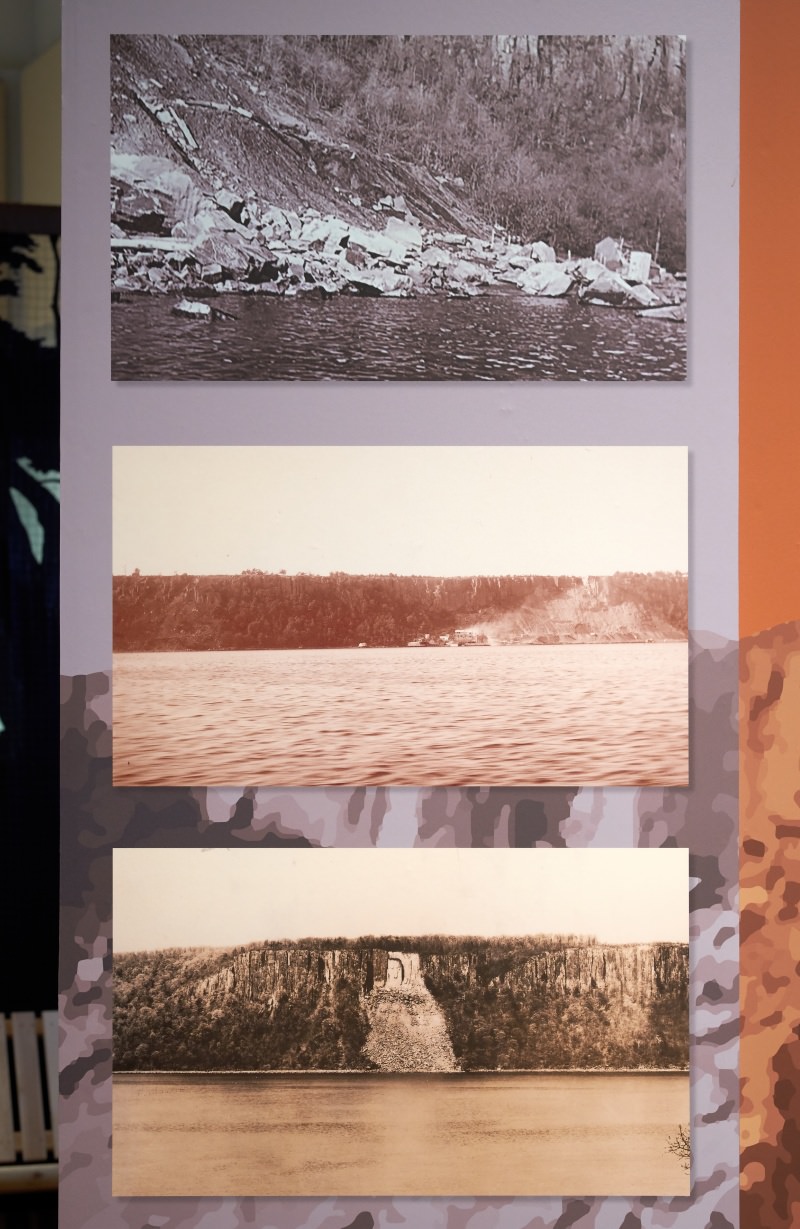

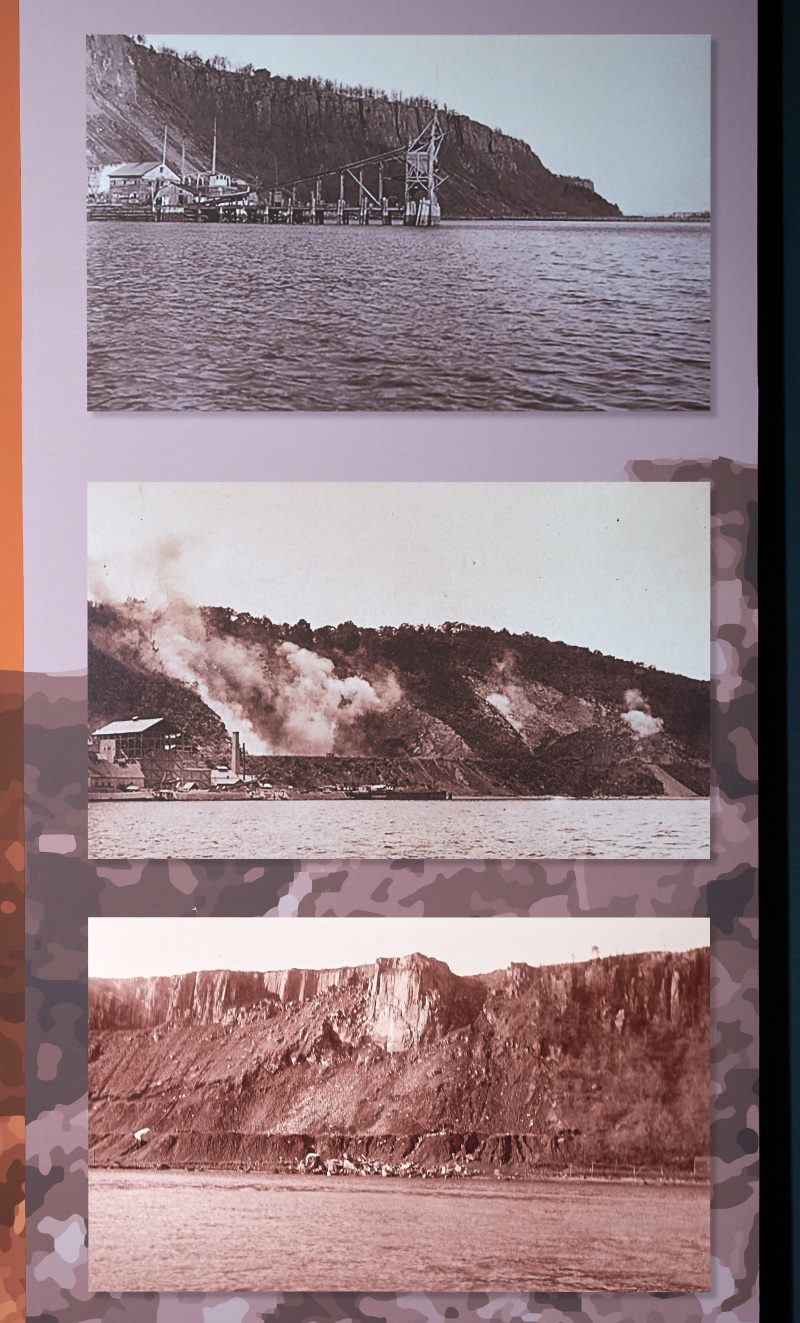

Blasting the Palisades

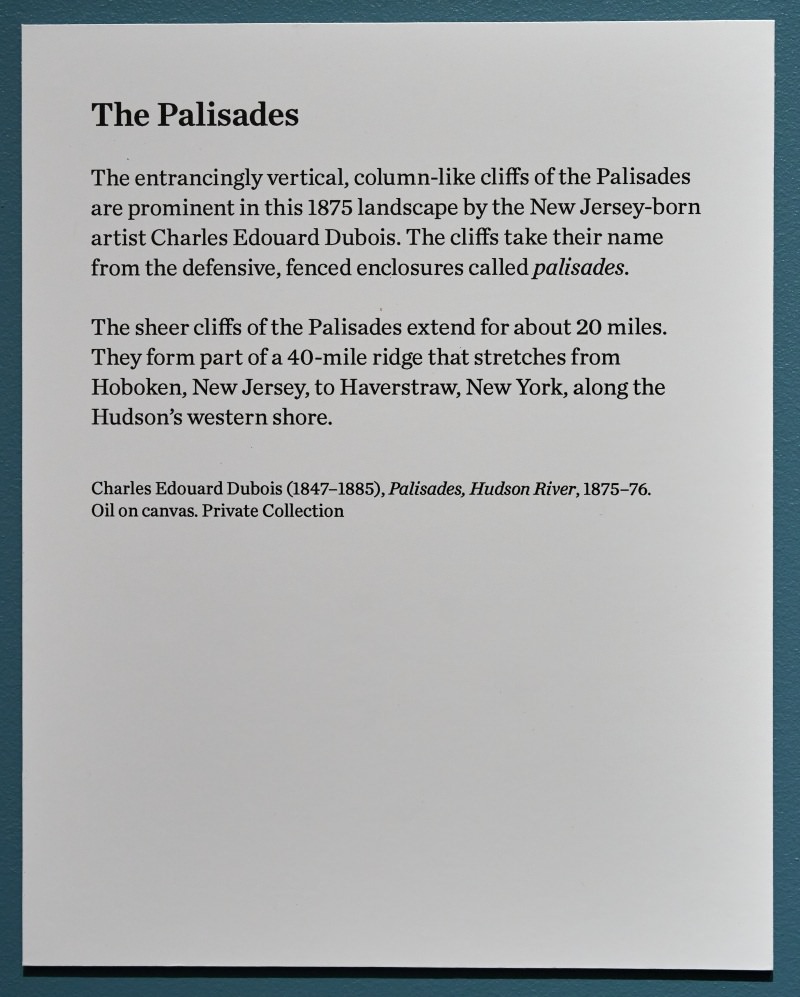

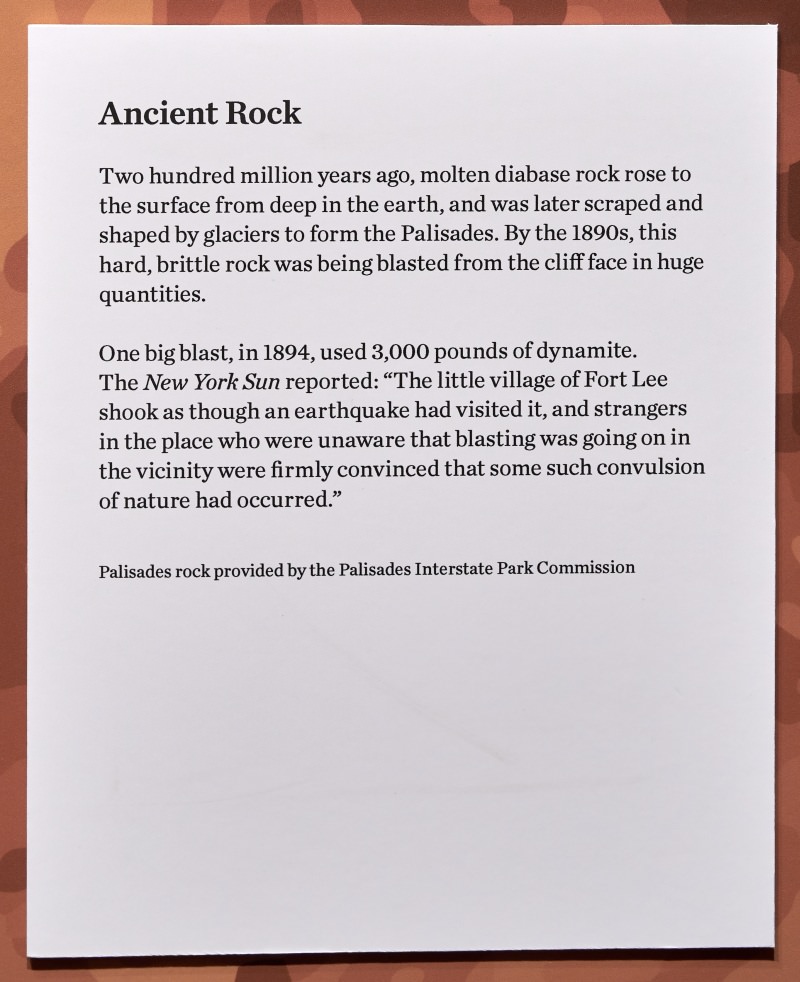

The hard rock of the Palisades lent itself perfectly to the construction of docks, roads, and concrete foundations that New York City needed as it grew. At first, entrepreneurs collected the rock that had fallen to the cliff base. In the 1890s, spurred by growing demand and improved dynamiting technology, they blasted the Palisades to obtain the rock.

The roar of dynamite shattered the nerves of residents on both sides of the river. Exploding rock flew through the windows of local homes. The famous forested cliffs of the Hudson began to disappear.

The destruction of the cliffs and forests troubled many, including a number of wealthy neighbors whose mansions across the river overlooked the Palisades.

The question was: How could they stop the blasting?

Saving the Palisades

The New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs took up the cause. The loss of the Palisades forest, which threatened the watershed, concerned them. The year was 1896, and women could not yet vote. So the members organized a grassroots lobbying campaign to stop companies from destroying the Palisades.

The American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society joined the battle in the interests of scenic beauty and local history. They, too, lobbied, and were heard by New York’s conservationist governor Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1899, Governor Roosevelt and New Jersey governor Foster Voorhees asked the advocates to propose a solution. The result? The Palisades Interstate Park Commission was formed, authorized to acquire the cliffs and turn the Palisades into a park.

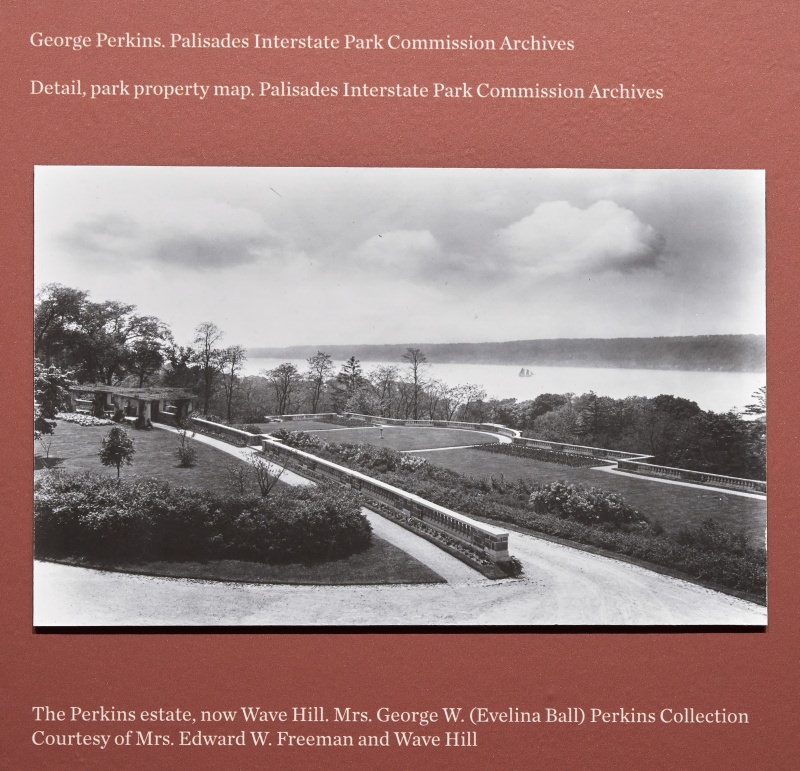

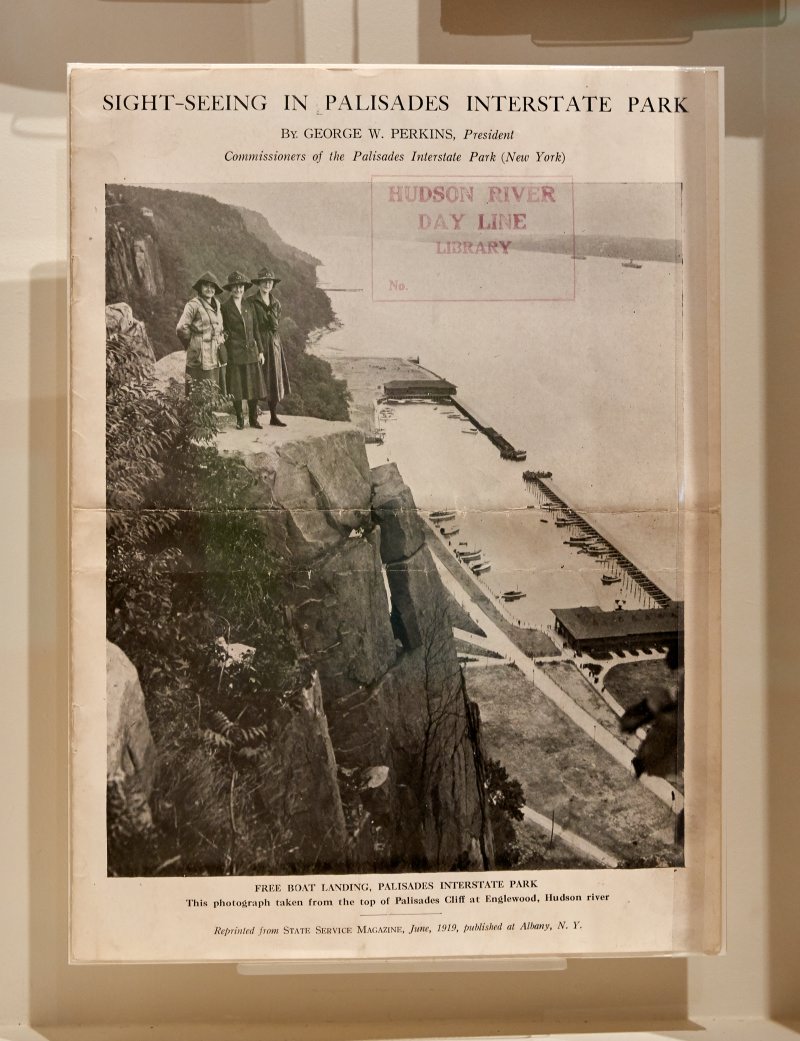

In 1900, the Commission began its work. Its leader, George Perkins, whose Riverdale mansion faced the Palisades, used public and private funds to buy up the land. By the time Palisades Interstate Park officially opened in 1909, it was already a destination.

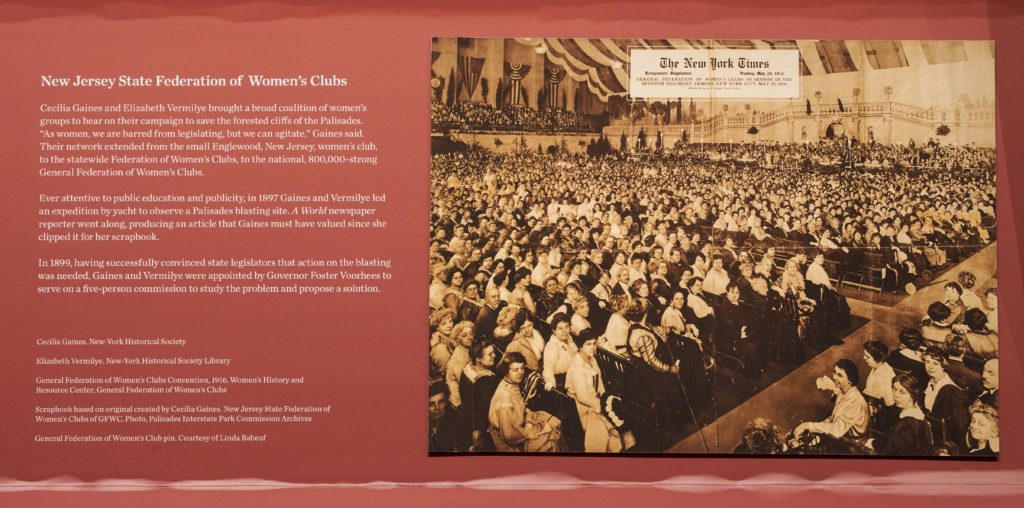

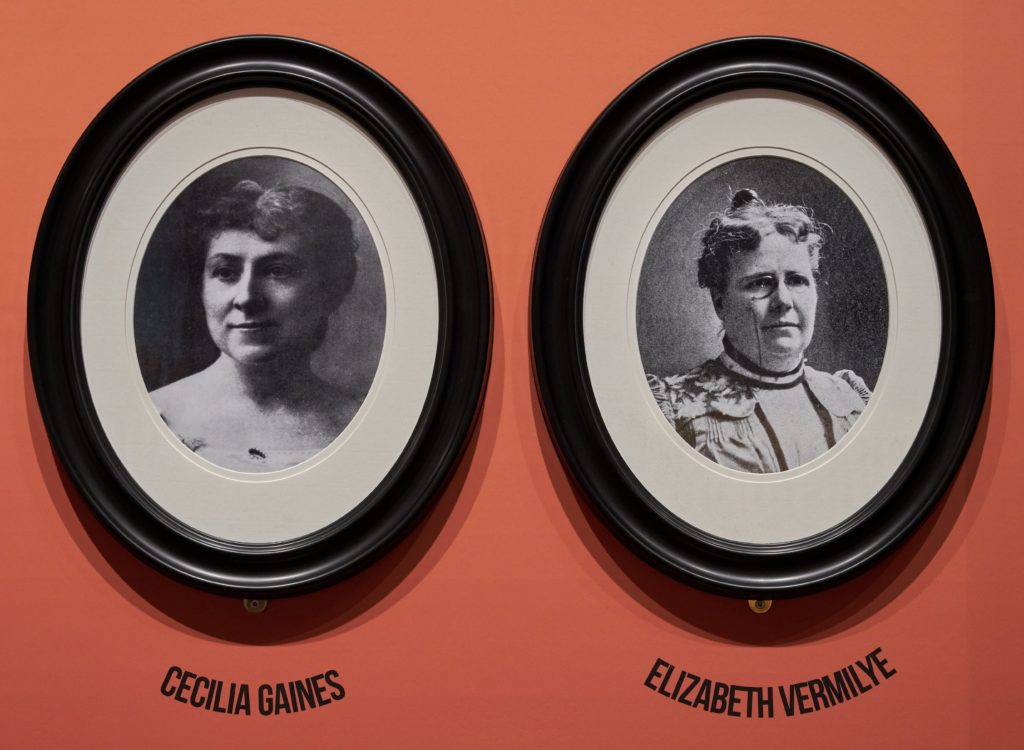

New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs

Cecilia Gaines and Elizabeth Vermilye brought a broad coalition of women’s groups to bear on their campaign to save the forested cliffs of the Palisades. “As women, we are barred from legislating, but we can agitate,” Gaines said. Their network extended from the small Englewood, New Jersey, women’s club, to the statewide Federation of Women’s Clubs, to the national, 800,000-strong General Federation of Women’s Clubs.

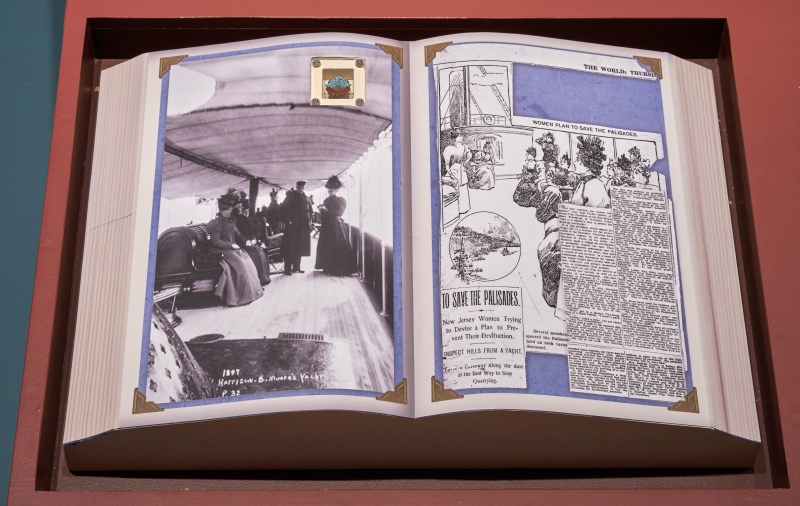

Ever attentive to public education and publicity, in 1897 Gaines and Vermilye led an expedition by yacht to observe a Palisades blasting site. A World newspaper reporter went along, producing an article that Gaines must have valued since she clipped it for her scrapbook.

In 1899, having successfully convinced state legislators that action on the blasting was needed, Gaines and Vermilye were appointed by Governor Foster Voorhees to serve on a five-person commission to study the problem and propose a solution.

Environmental Advocacy

Concern for forests and watersheds ranked high among the clubwomen, just as it did for advocates in the Adirondacks. While assembled at a convention in 1896, the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs presented maps, photos, and pamphlets to argue for the importance of scientific forestry and protection for the Palisades. The General Federation followed suit, pledging to combat the “wicked and wasteful destruction of our forest cover.”

In 1897, the New Jersey clubwomen’s Committee on Forestry and Protection of the Palisades set up a traveling forestry library for schools and libraries. Encased in oak shelving, the books and reports addressed a sophisticated range of topics in order to inform the public about the newest scholarship and government action.

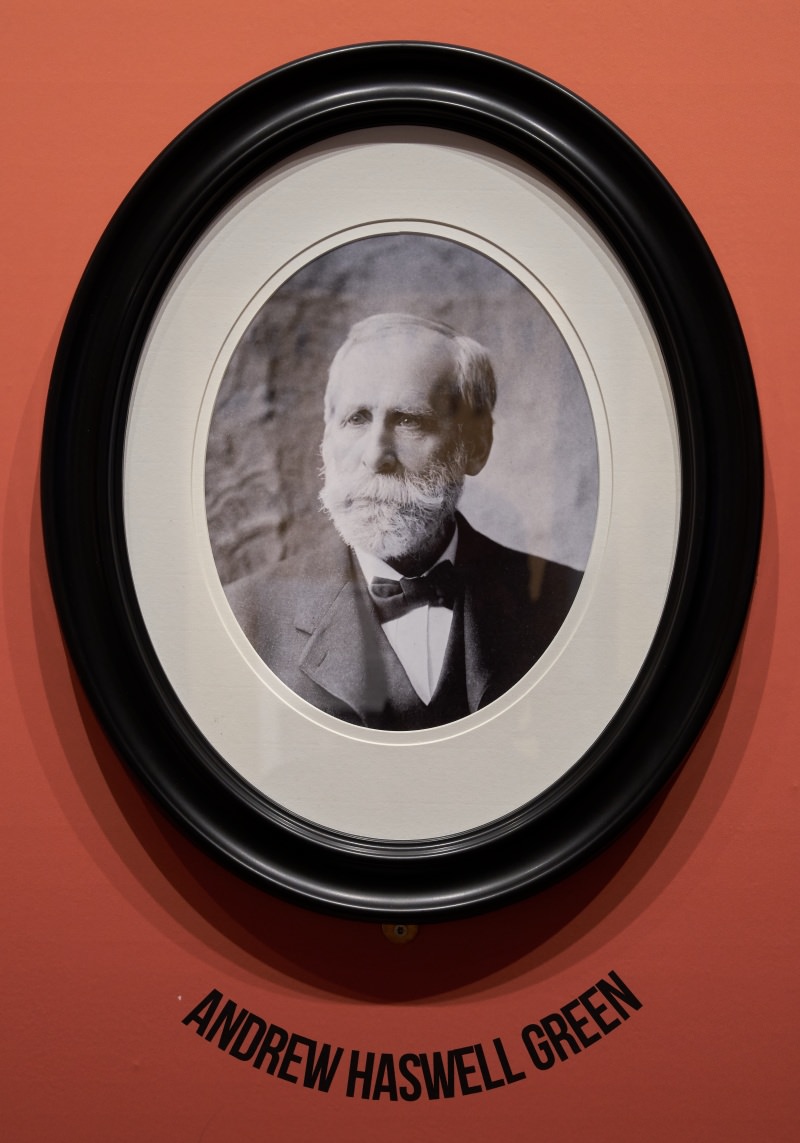

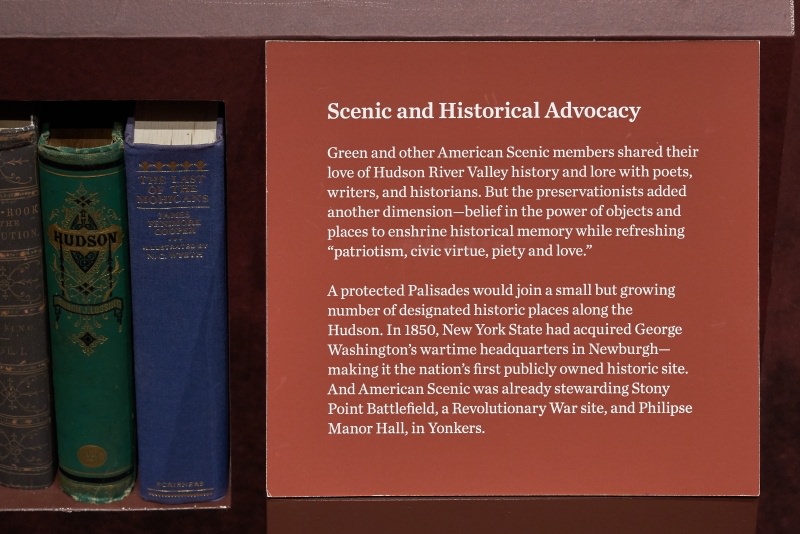

American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society

Civic leader Andrew Haswell Green brought the experience of long term public service to his involvement in the Palisades. As head of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (est. 1895), Green and his fellow preservationists sought to “preserve from disfigurement beautiful features of the natural landscape” and save historic places and objects from destruction. The Palisades became their cause.

While the women’s clubs pressed for action in New Jersey, Green’s American Scenic did so in New York. Then, in 1898, conservationist Theodore Roosevelt won the governorship. Roosevelt endorsed Green’s idea of establishing a New York study commission to work in tandem with the New Jerseyans and propose a solution.

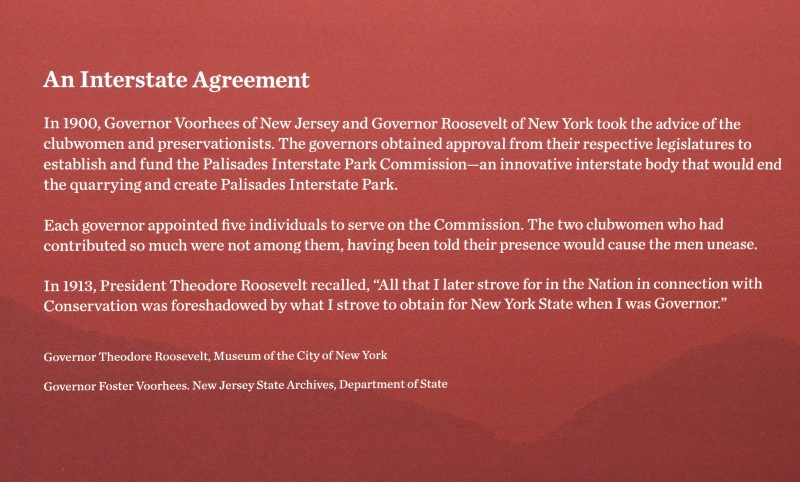

An Interstate Agreement

In 1900, Governor Voorhees of New Jersey and Governor Roosevelt of New York took the advice of the clubwomen and preservationists. The governors obtained approval from their respective legislatures to establish and fund the Palisades Interstate Park Commission—an innovative interstate body that would end the quarrying and create Palisades Interstate Park.

Each governor appointed five individuals to serve on the Commission. The two clubwomen who had contributed so much were not among them, having been told their presence would cause the men unease.

In 1913, President Theodore Roosevelt recalled, “All that I later strove for in the Nation in connection with Conservation was foreshadowed by what I strove to obtain for New York State when I was Governor.”

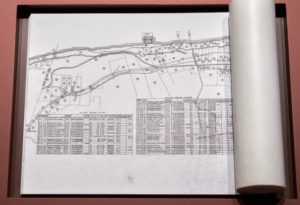

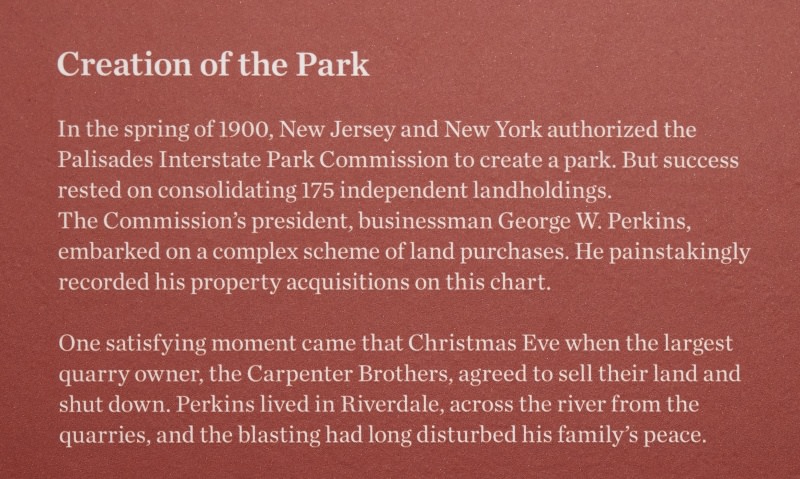

Creation of the Park

In the spring of 1900, New Jersey and New York authorized the Palisades Interstate Park Commission to create a park. But success rested on consolidating 175 independent landholdings.

The Commission’s president, businessman George W. Perkins, embarked on a complex scheme of land purchases. He painstakingly recorded his property acquisitions on this chart.

One satisfying moment came that Christmas Eve when the largest quarry owner, the Carpenter Brothers, agreed to sell their land and shut down. Perkins lived in Riverdale, across the river from the quarries, and the blasting had long disturbed his family’s peace.

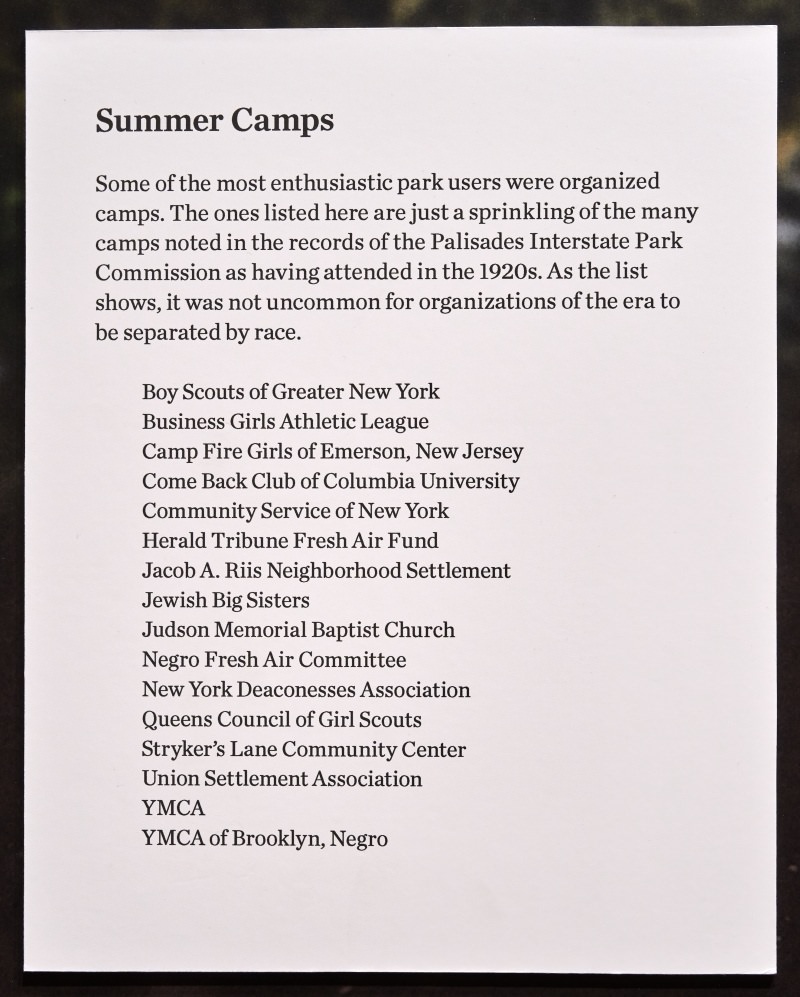

A Park for the People

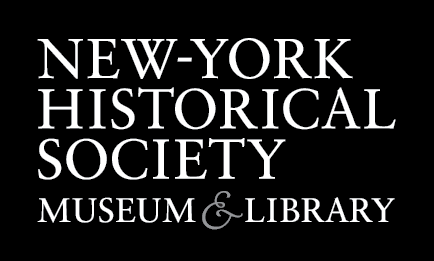

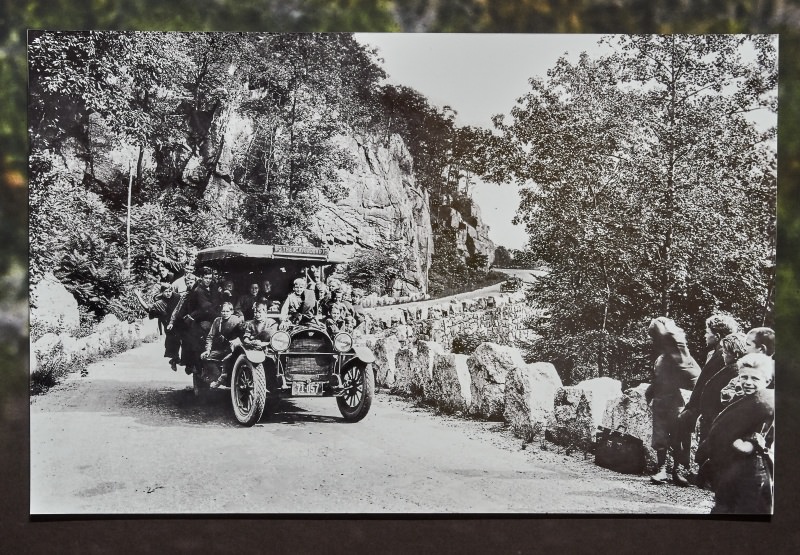

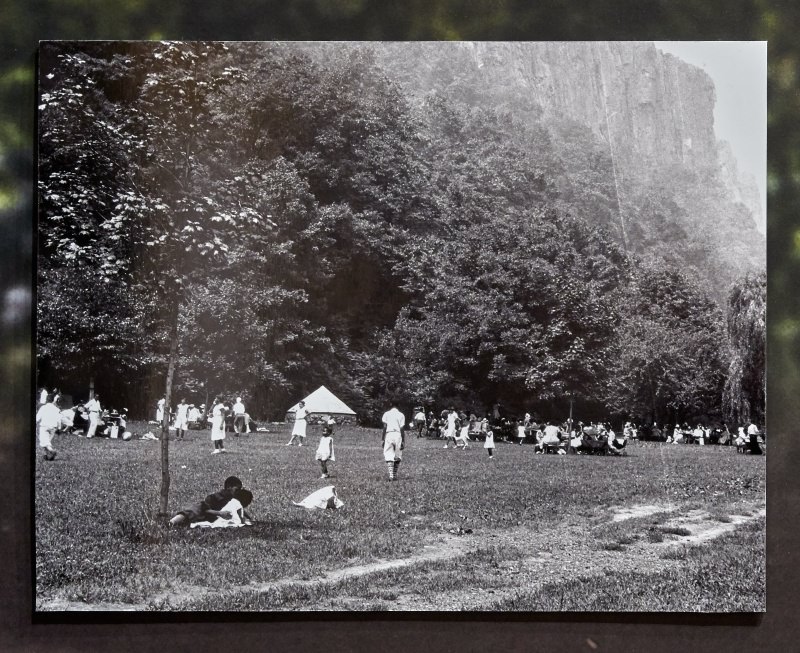

Residents of New York and New Jersey thronged to Palisades Interstate Park, arriving by foot, ferry, train, nand car. Over two million visited in 1920 alone.

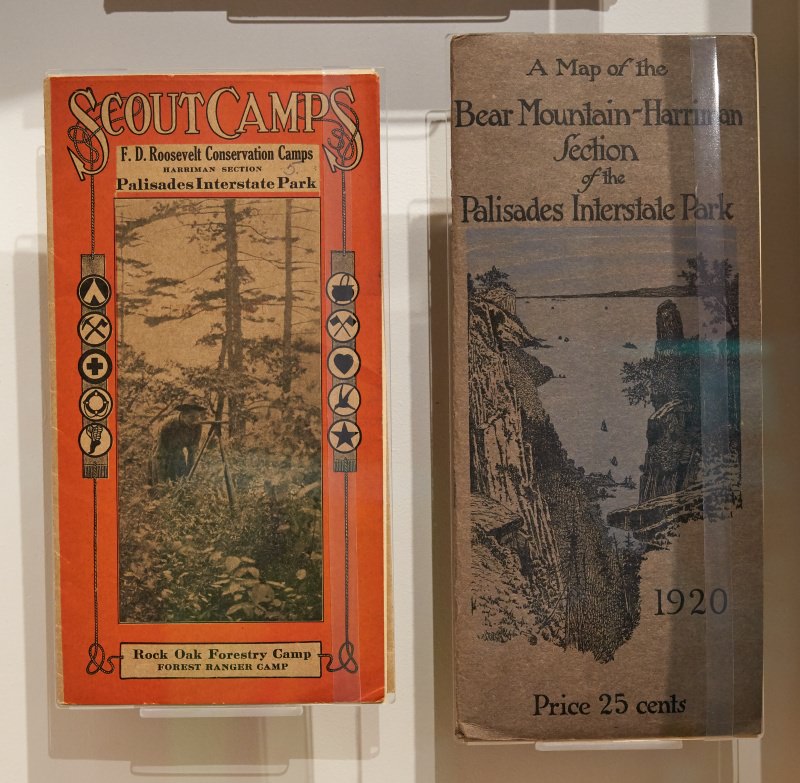

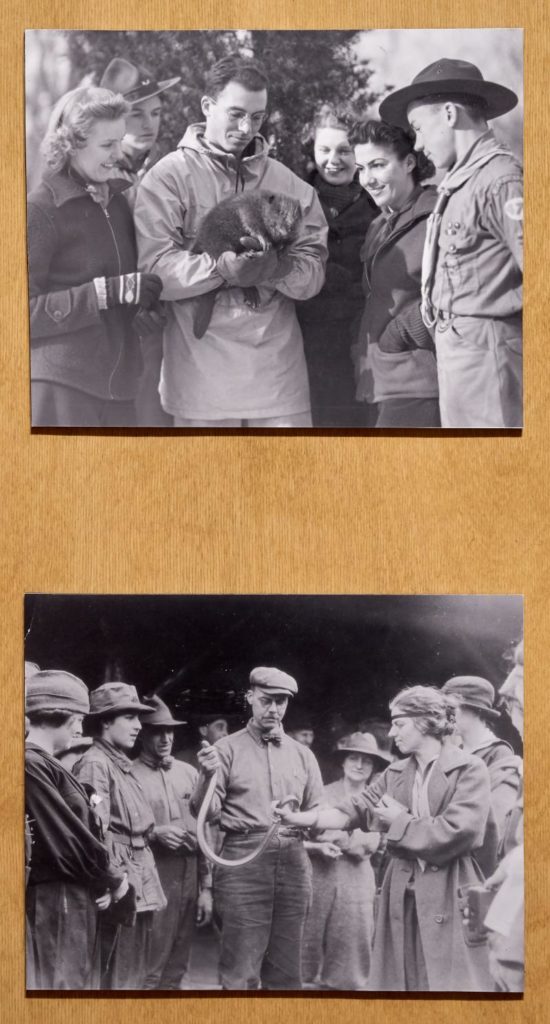

What a contrast the Palisades made to the dirty, crowded streets of the Lower East Side. Franklin D. Roosevelt, while holding the position of New York Boy Scouts president, was among the many civic leaders who nrecognized the park’s usefulness in improving public health and teaching good citizenship, especially among immigrants arriving at Ellis Island by the hundreds of thousands.

One set of young working women found refuge in the park when garment-factory jobs dried up. Camping in the open, replenished by “fresh air, sunshine and the lovely Hudson,” the friends returned to the city ready to mobilize for social justice. They soon spearheaded the largest rent strike New York City had yet seen.

The park started with the riverfront. It expanded inland, in 1910, after Edward and Mary Harriman donated 10,000 acres, spurring the creation of Harriman and Bear Mountain State Parks. The Palisades Interstate Park Commission operated these additions, along with other parks added later. The ambitious construction of camps, trails, beaches, and boathouses, along with new roads and bridges, made the Palisades parks the most popular in the country.

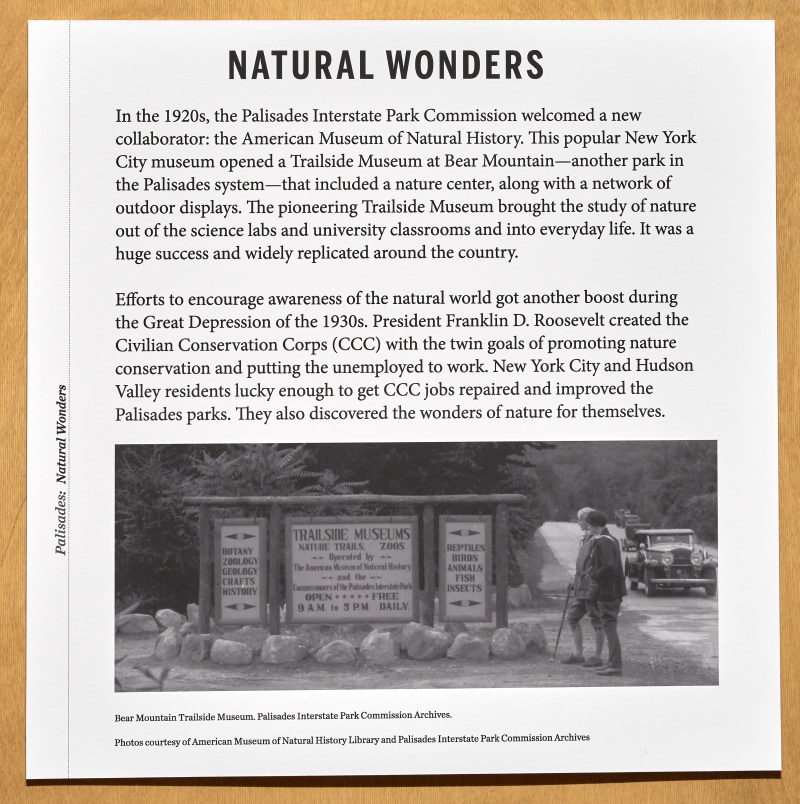

Natural Wonders

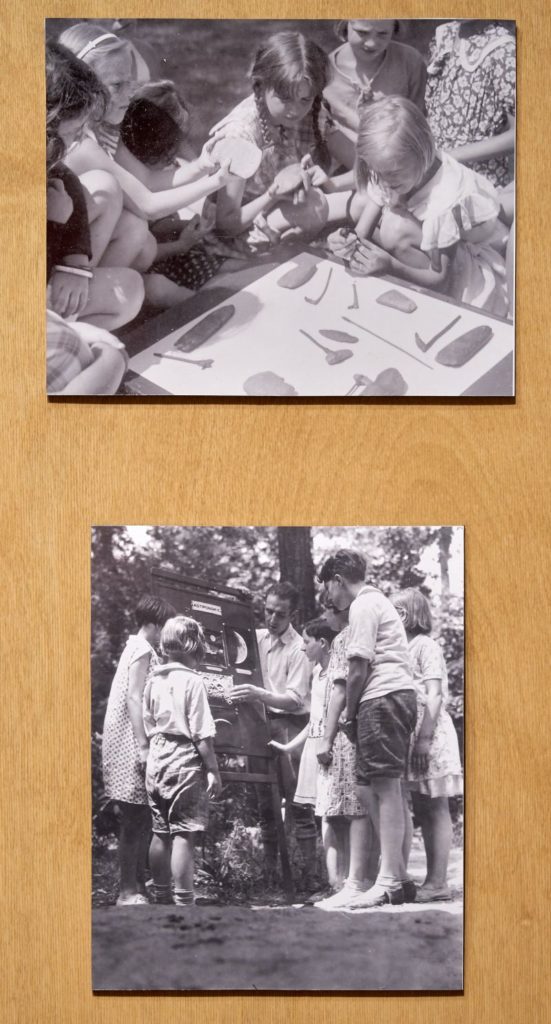

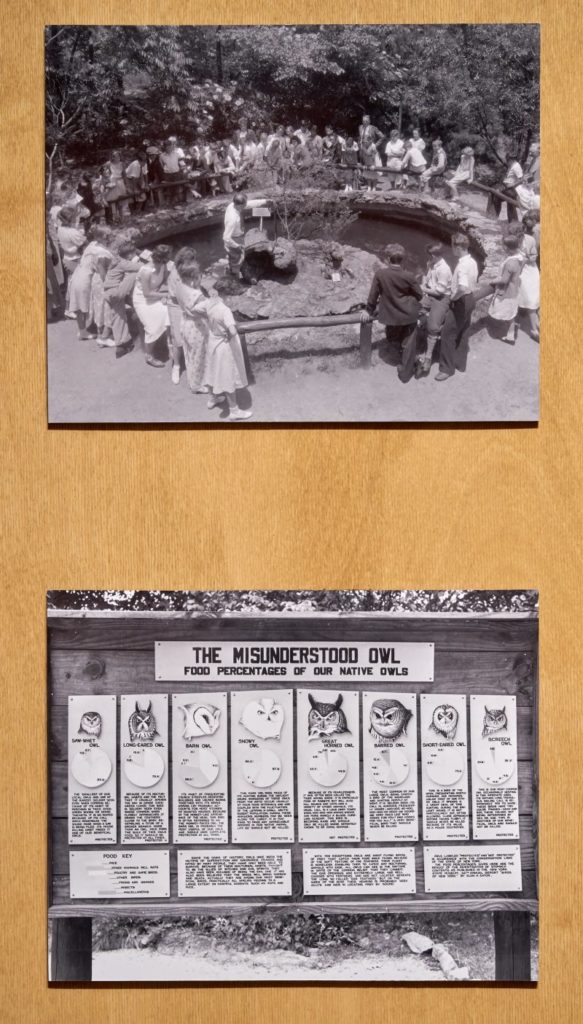

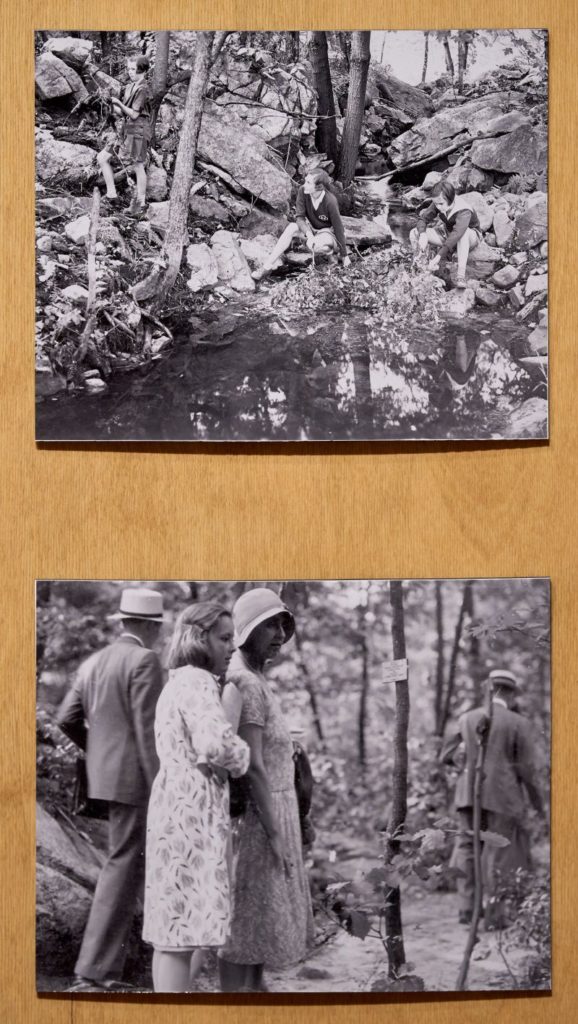

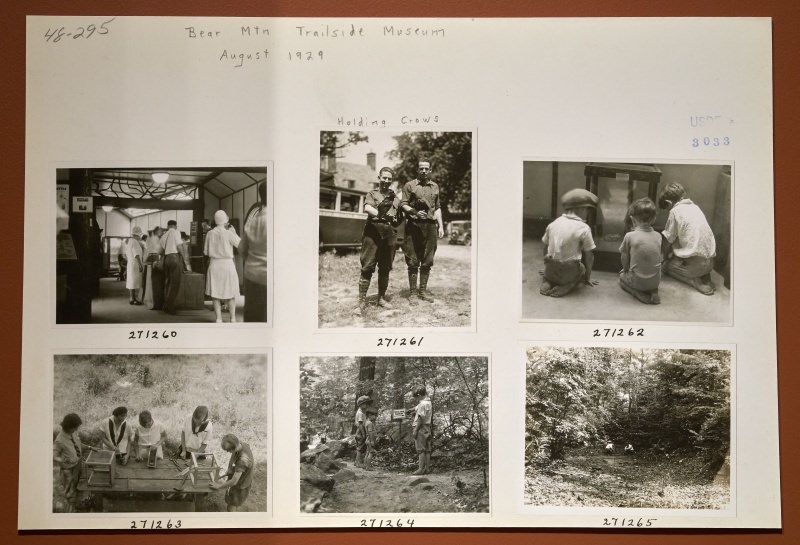

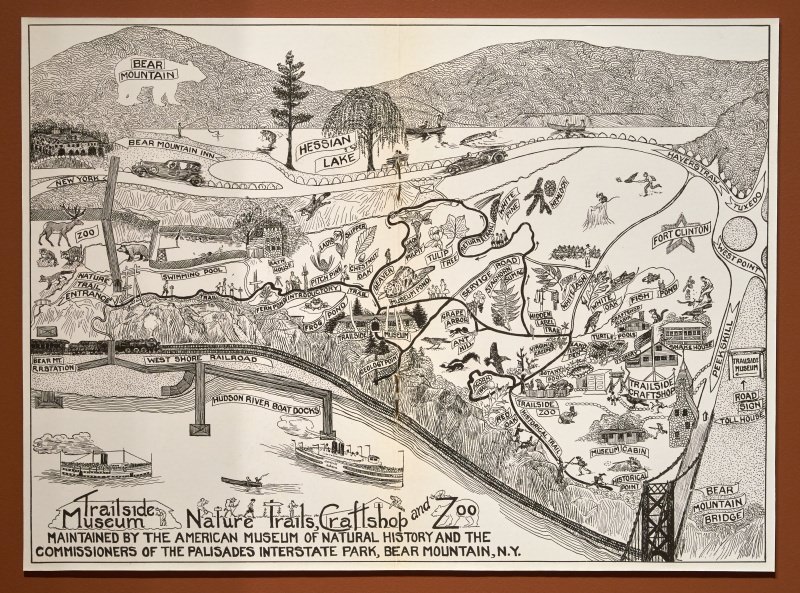

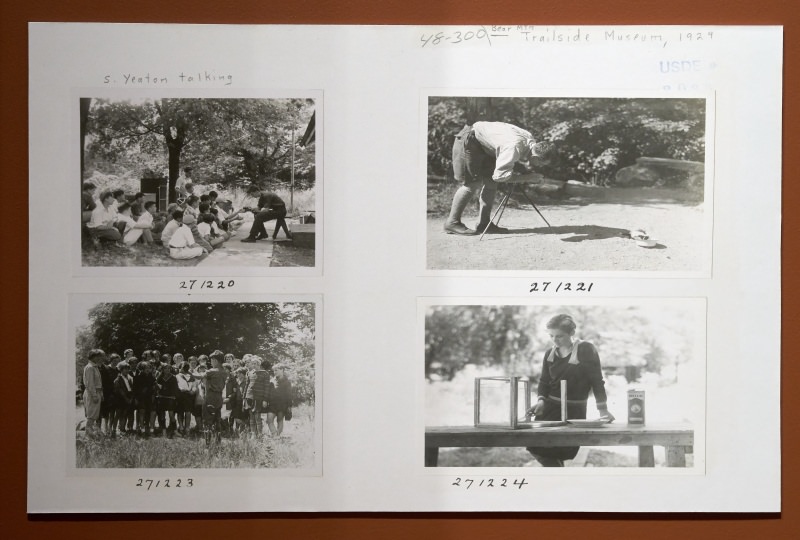

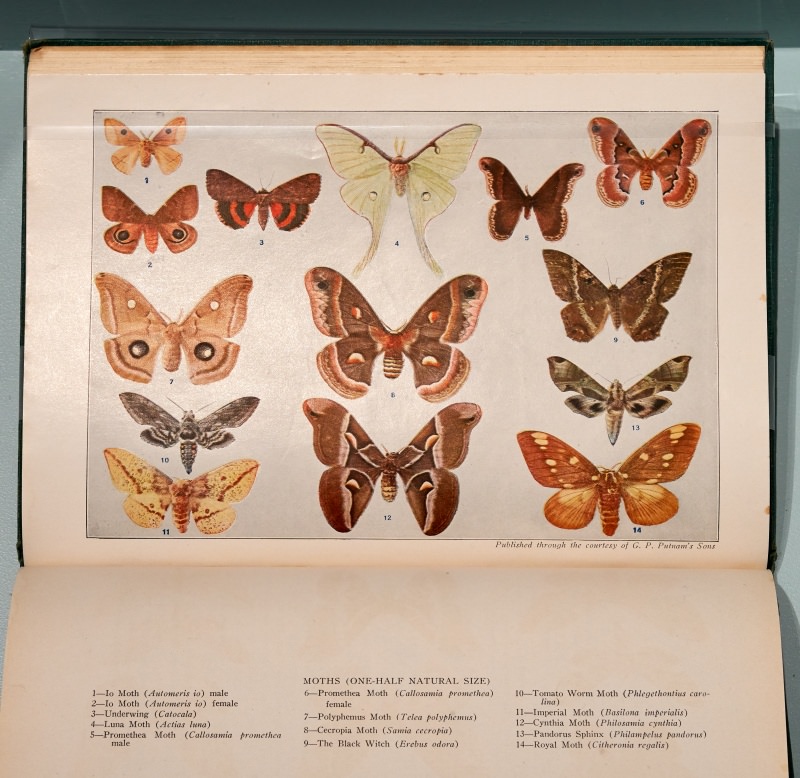

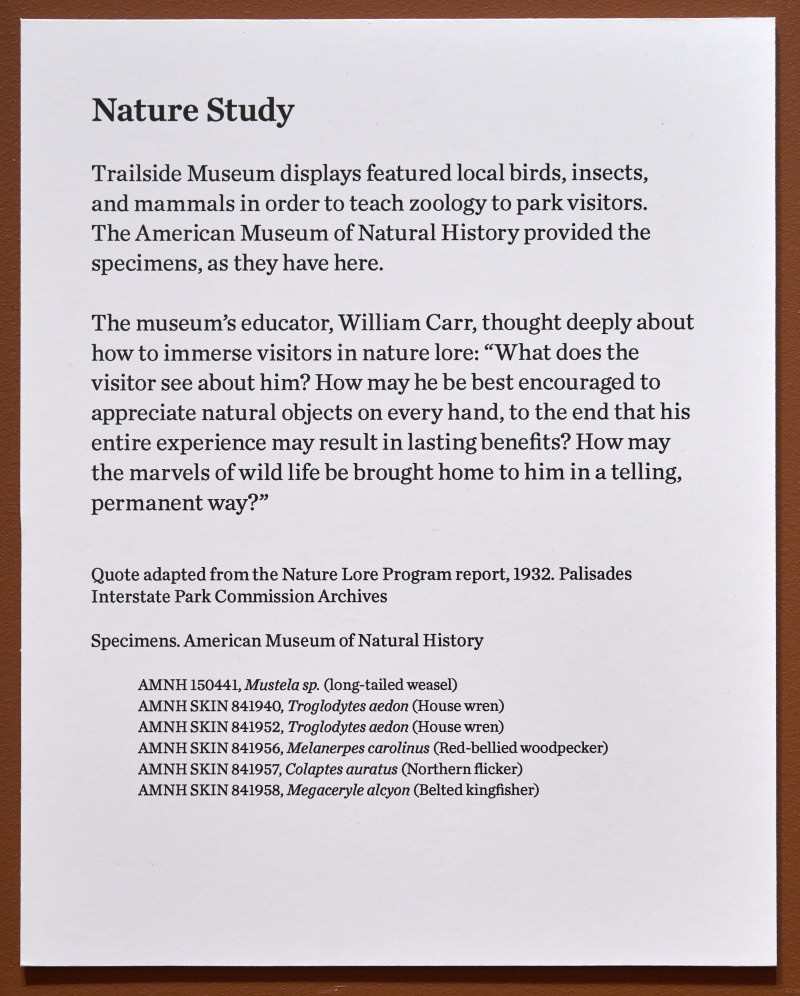

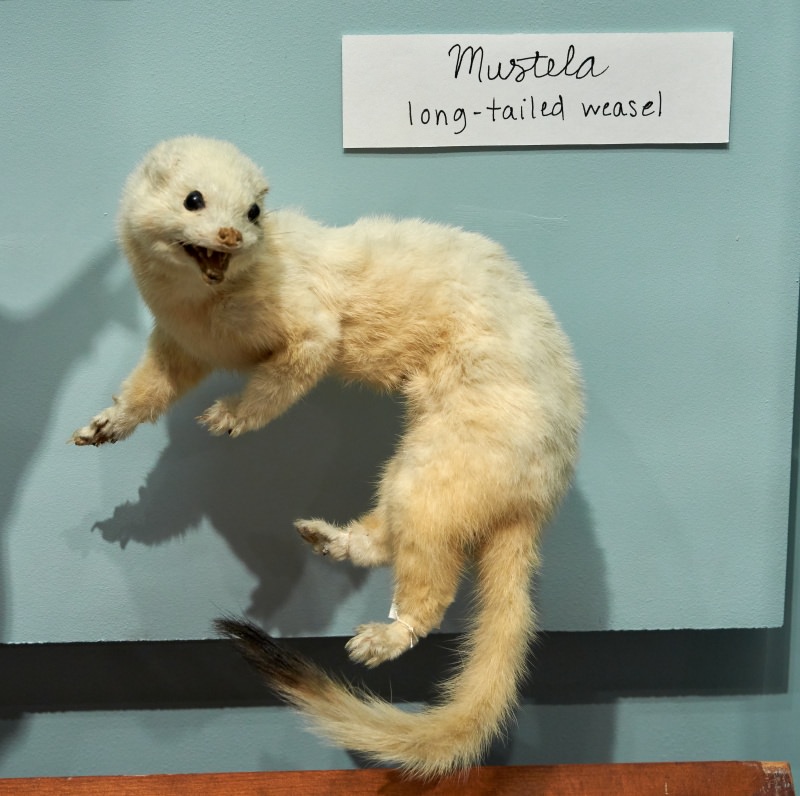

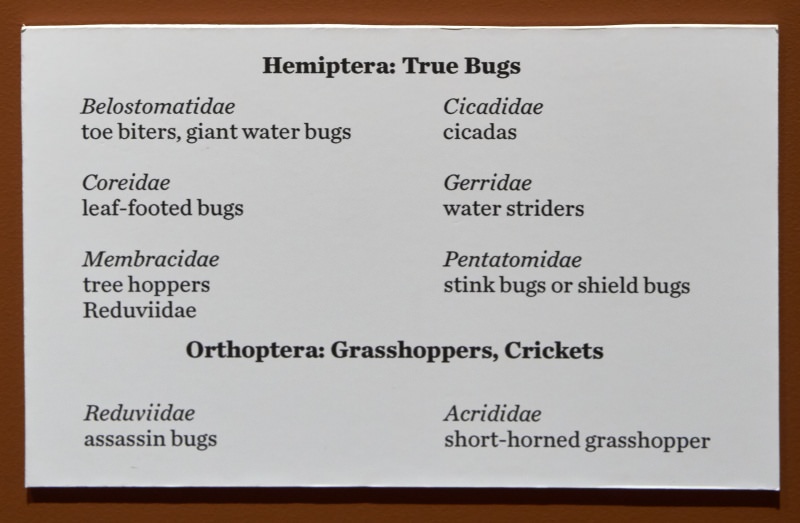

In the 1920s, the Palisades Interstate Park Commission welcomed a new collaborator: the American Museum of Natural History. This popular New York City museum opened a Trailside Museum at Bear Mountain—another park in the Palisades system—that included a nature center, along with a network of outdoor displays. The pioneering Trailside Museum brought the study of nature out of the science labs and university classrooms and into everyday life. It was a huge success and widely replicated around the country.

Efforts to encourage awareness of the natural world got another boost during the Great Depression of the 1930s. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) with the twin goals of promoting nature conservation and putting the unemployed to work. New York City and Hudson Valley residents lucky enough to get CCC jobs repaired and improved the Palisades parks. They also discovered the wonders of nature for themselves.

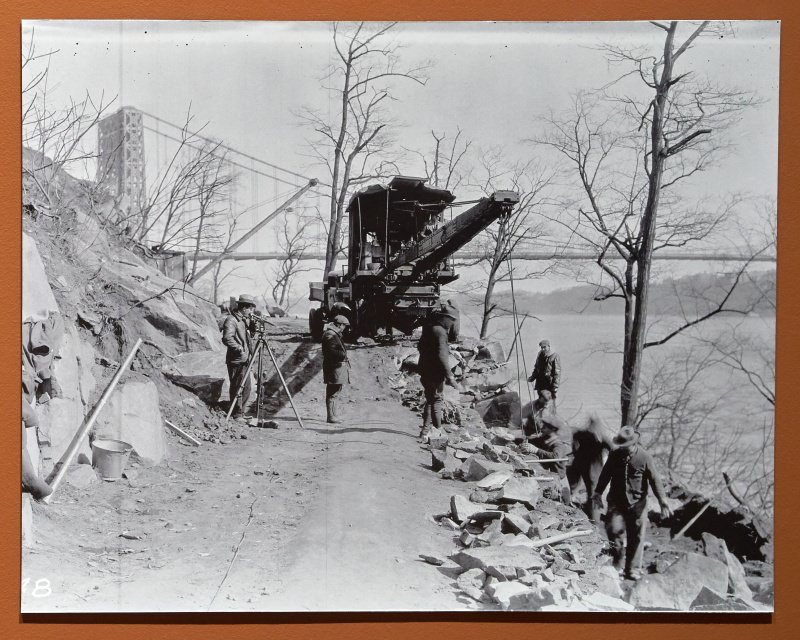

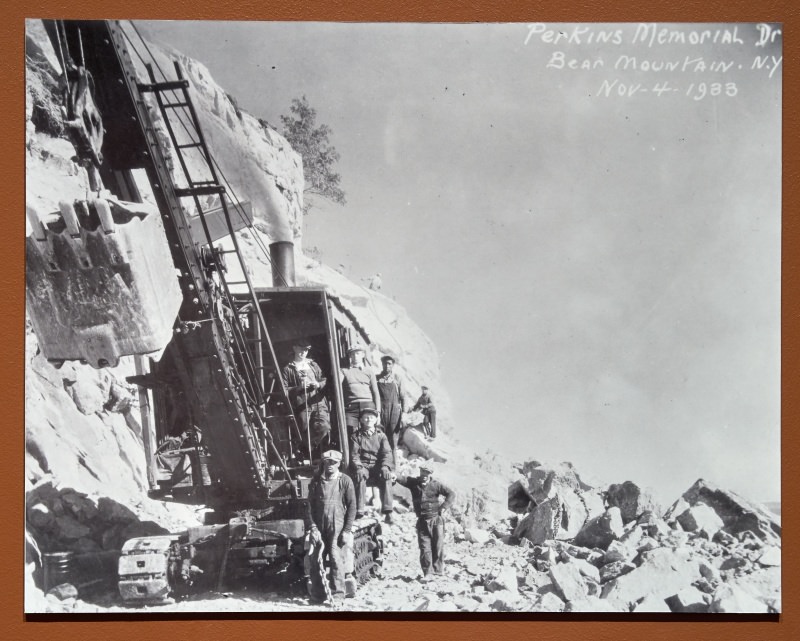

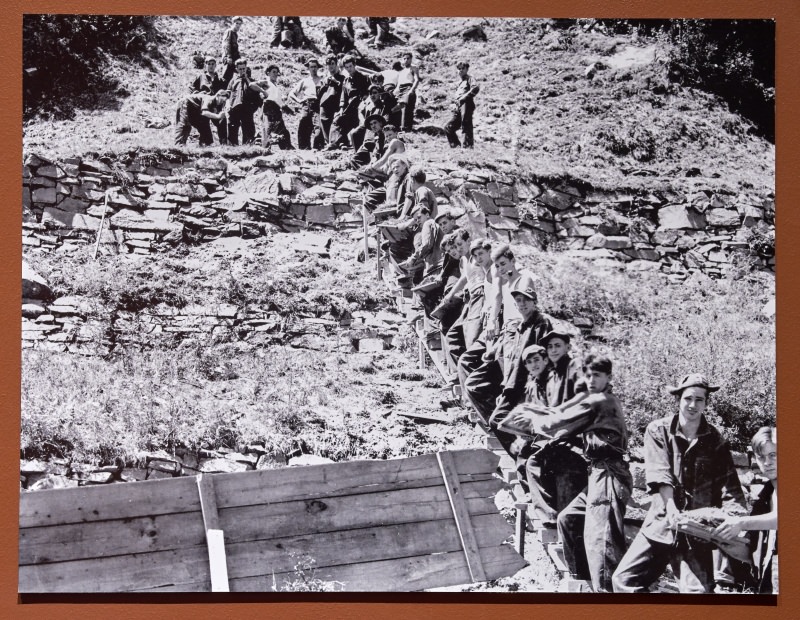

Civilian Conservation Corps

These images show enrollees in President Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) at work in the Palisades parks. From 1933 to 1942, during the Great Depression, the federal government employed millions of young, single men to restore and improve the nation’s resources. The workers lived in CCC camps while they planted trees, slowed soil erosion, developed state parks and hiking trails, stocked rivers with fish, and built fences and small reservoirs throughout the United States.

Roosevelt supplemented the training with voluntary night classes. To test his idea, he asked the Palisades Interstate Park Commission to arrange “some kind of informal instruction in forestry and the natural history of trees.” Within two years, most CCC enrollees around the country were attending classes. Forestry, landscaping, and nature study were particularly popular.

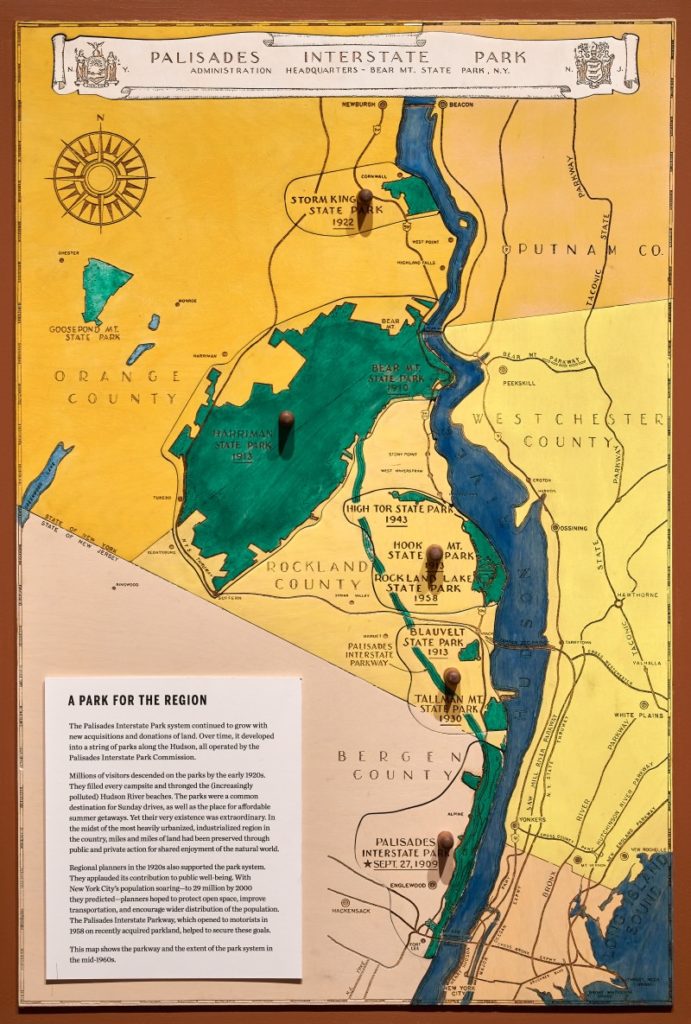

A Park for the Region

The Palisades Interstate Park system continued to grow with new acquisitions and donations of land. Over time, it developed into a string of parks along the Hudson, all operated by the Palisades Interstate Park Commission.

Millions of visitors descended on the parks by the early 1920s. They filled every campsite and thronged the (increasingly polluted) Hudson River beaches. The parks were a common destination for Sunday drives, as well as the place for affordable summer getaways. Yet their very existence was extraordinary. In the midst of the most heavily urbanized, industrialized region in the country, miles and miles of land had been preserved through public and private action for shared enjoyment of the natural world.

Regional planners in the 1920s also supported the park system. They applauded its contribution to public well-being. With New York City’s population soaring—to 29 million by 2000 they predicted—planners hoped to protect open space, improve transportation, and encourage wider distribution of the population. The Palisades Interstate Parkway, which opened to motorists in 1958 on recently acquired parkland, helped to secure these goals.

This map shows the parkway and the extent of the park system in the mid-1960s.