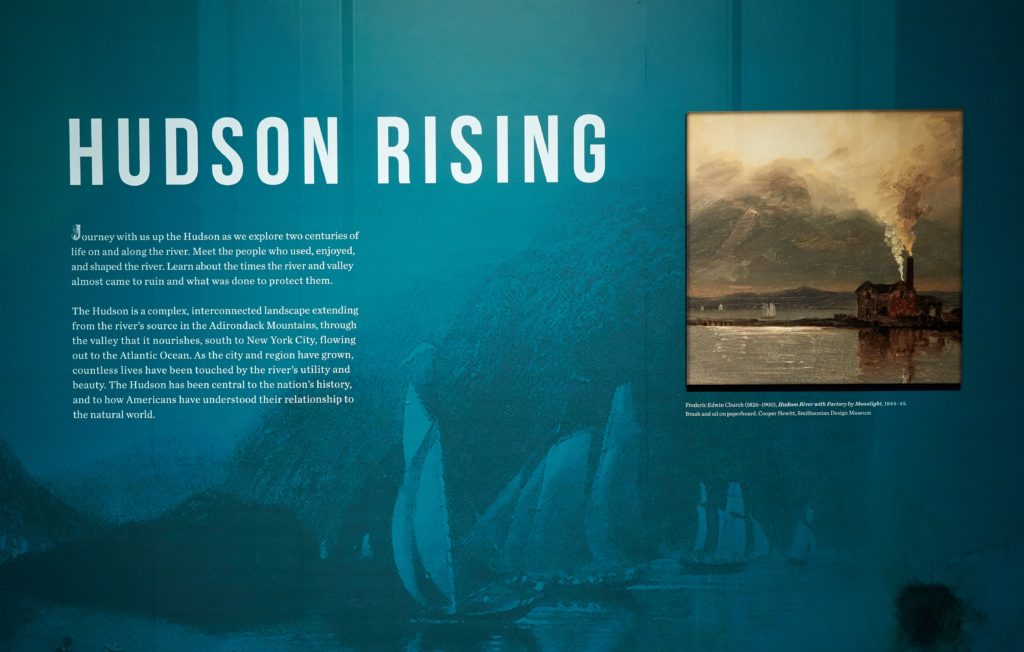

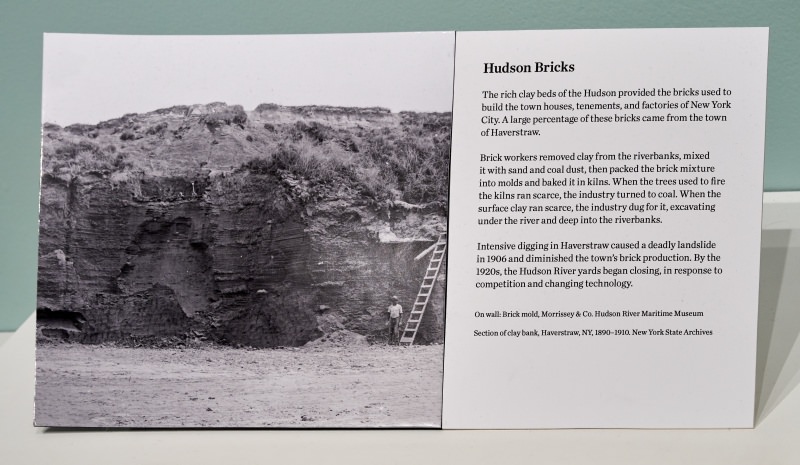

Hudson Rising

Journey with us up the Hudson as we explore two centuries of life on and along the river. Meet the people who used, enjoyed, and shaped the river. Learn about the times the river and valley almost came to ruin and what was done to protect them.

The Hudson is a complex, interconnected landscape extending from the river’s source in the Adirondack Mountains, through the valley that it nourishes, south to New York City, flowing out to the Atlantic Ocean. As the city and region have grown, countless lives have been touched by the river’s utility and beauty. The Hudson has been central to the nation’s history, and to how Americans have understood their relationship to the natural world.

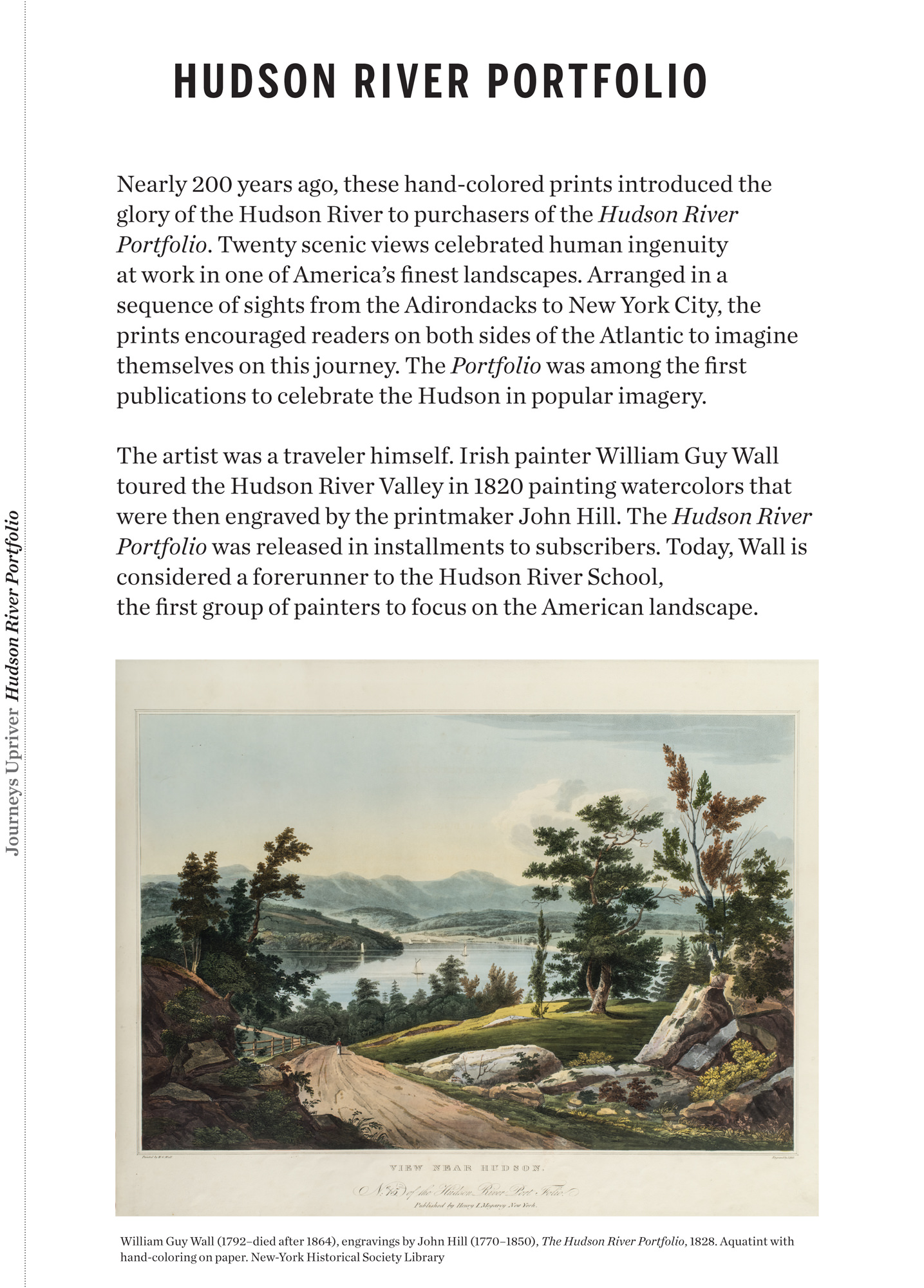

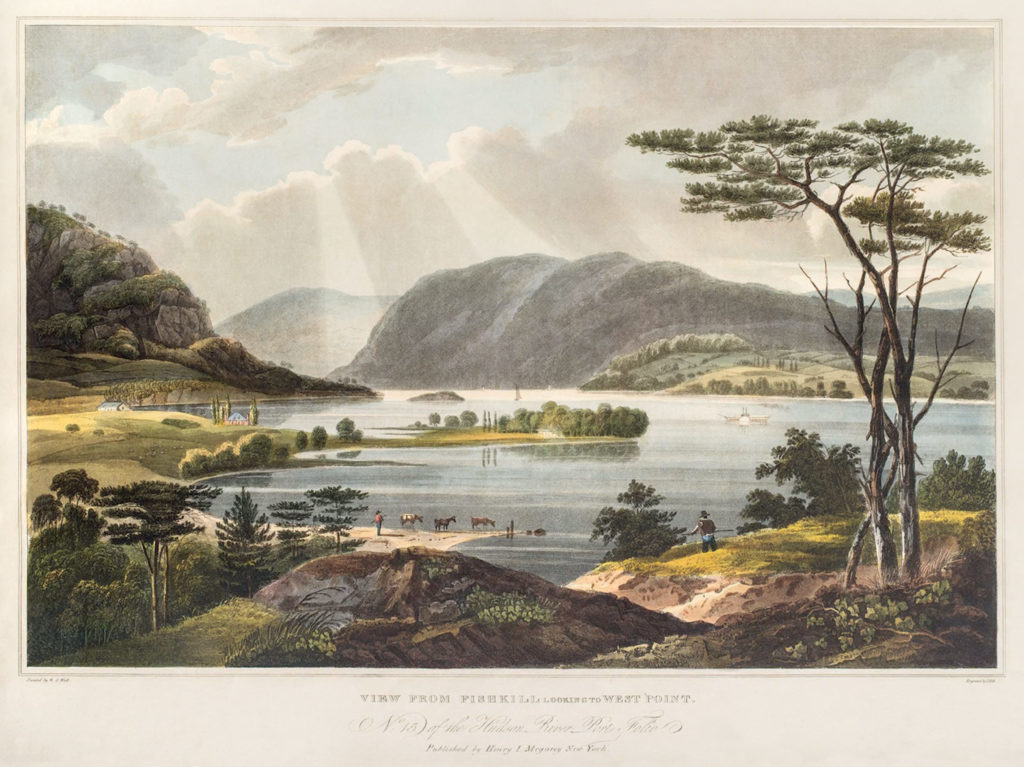

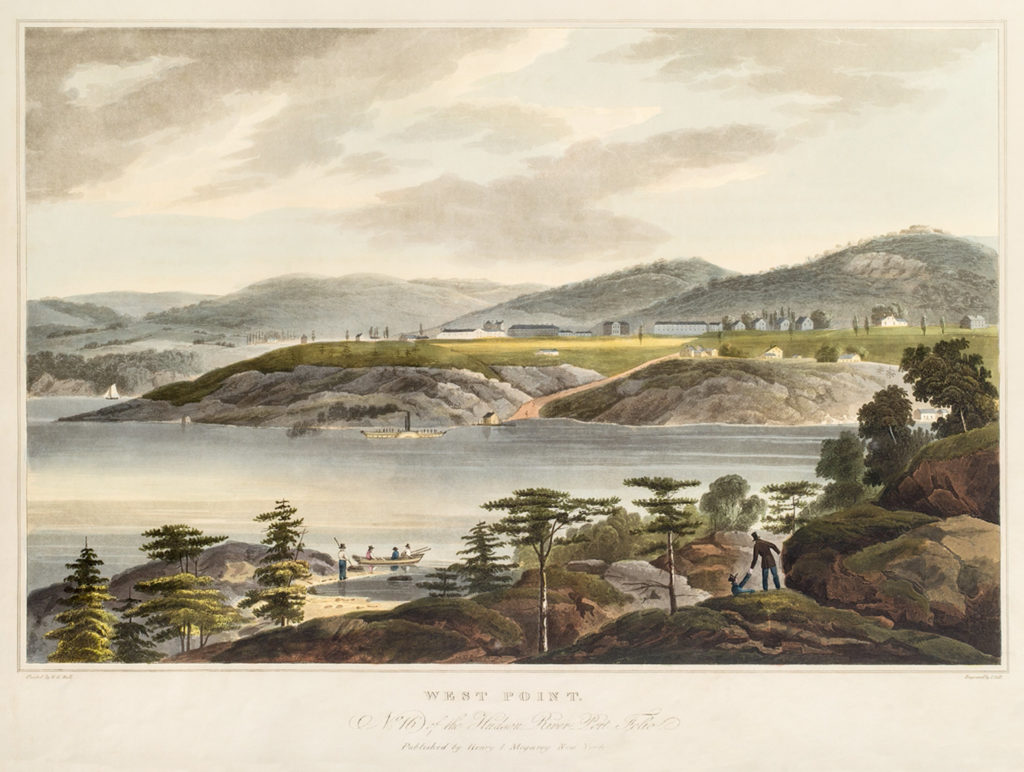

Hudson River Portfolio

Nearly 200 years ago, these hand-colored prints introduced the glory of the Hudson River to purchasers of the Hudson River Portfolio. Twenty scenic views celebrated human ingenuity at work in one of America’s finest landscapes. Arranged in a sequence of sights from the Adirondacks to New York City, the prints encouraged readers on both sides of the Atlantic to imagine themselves on this journey. The Portfolio was among the first publications to celebrate the Hudson in popular imagery.

The artist was a traveler himself. Irish painter William Guy Wall toured the Hudson River Valley in 1820 painting watercolors that were then engraved by the printmaker John Hill. The Hudson River Portfolio was released in installments to subscribers. Today, Wall is considered a forerunner to the Hudson River School, the first group of painters to focus on the American landscape.

Journeys Upriver: the 1800s

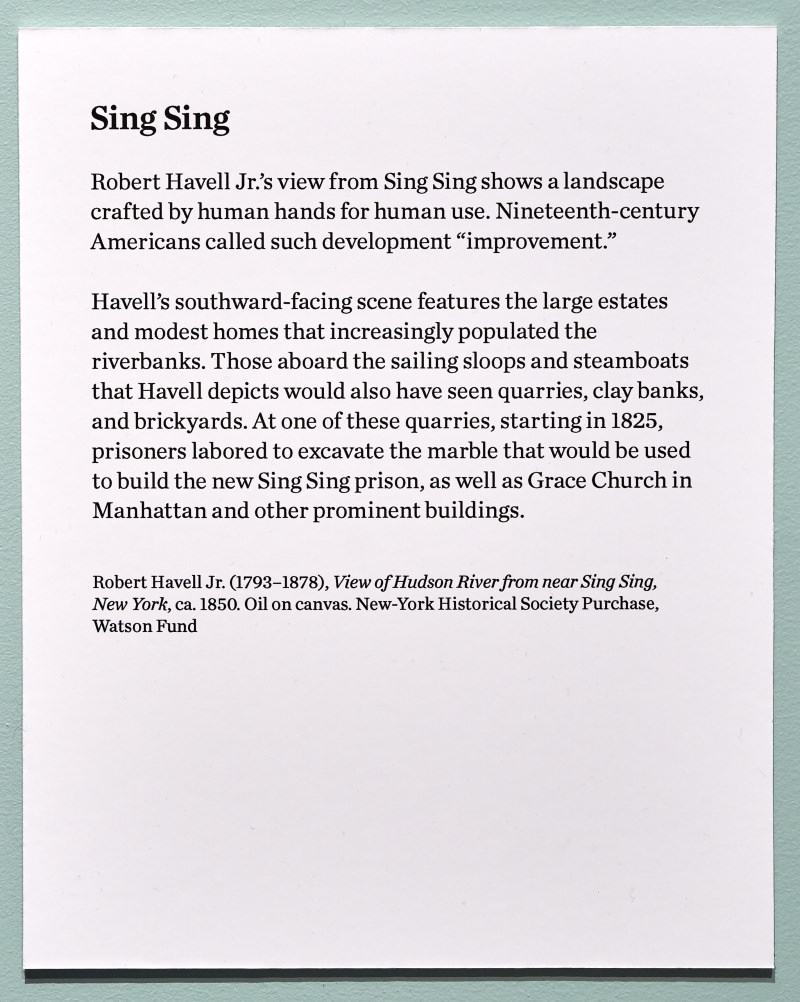

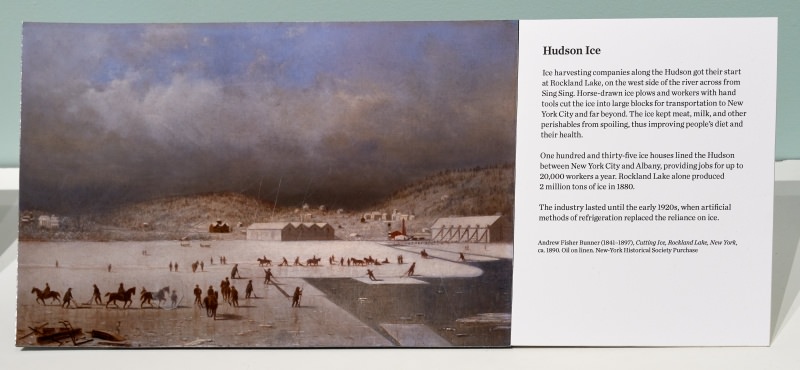

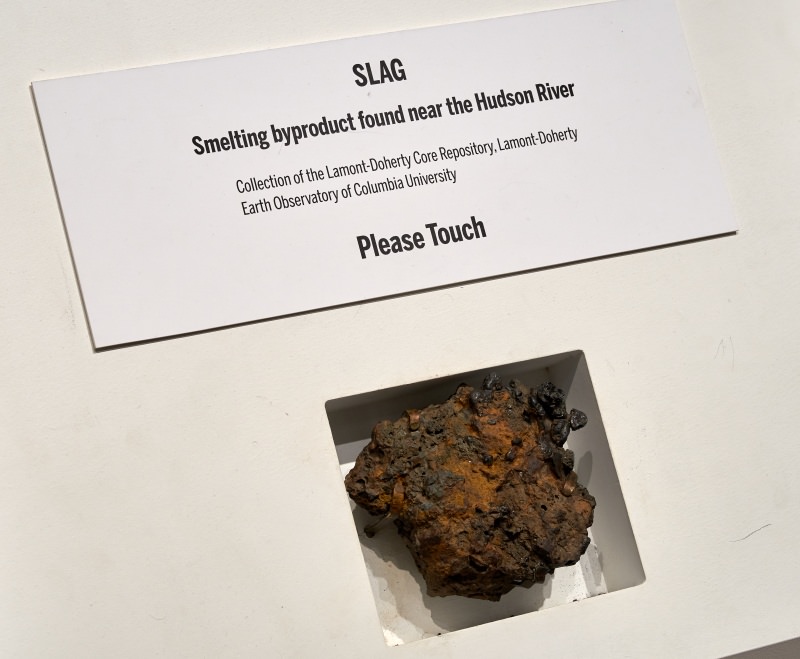

Beginning in 1807, wood- and then coal-fired steamboats made Hudson journeys easy, cheap, and reliable. Sailing sloops and steamboats carried people and manufactured goods upriver. They brought back ice, bricks, iron, coal, and lumber. Trade expanded, and the region prospered.

The river and its shores were shaped to accommodate steamboats. Wharves and piers extended into the river. Soft-edged shorelines were hardened and contained. River edges were diked, and the bottom dredged. The resulting deeper, straighter Hudson worked well for shipping. But the shallows that once supported plants and animals, filtered the water, and protected against flooding largely disappeared.

Nineteenth-century travelers on the Hudson witnessed the valley’s transformation. To most, it looked like improvement, but some saw it as desecration. Differing views about development led to contentious questions. Would all uses be permitted? Was scenic beauty as valuable as economic growth?

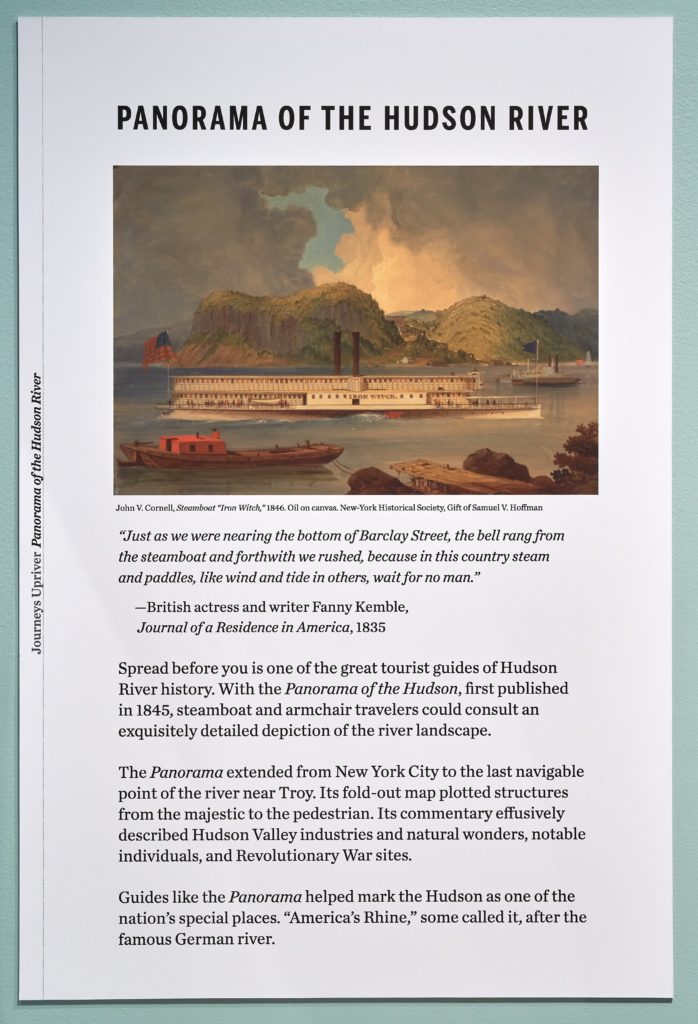

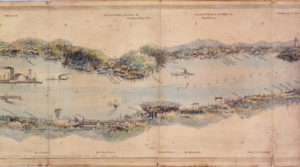

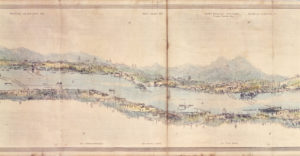

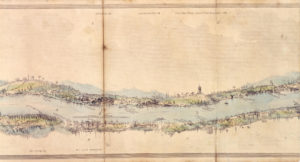

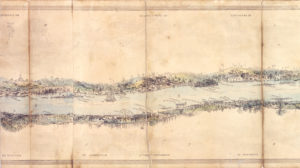

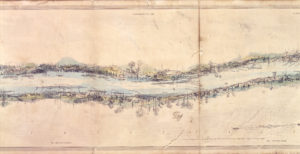

Panorama of the Hudson River

“Just as we were nearing the bottom of Barclay Street, the bell rang from the steamboat and forthwith we rushed, because in this country steam and paddles, like wind and tide in others, wait for no man.”

—British actress and writer Fanny Kemble, Journal of a Residence in America, 1835

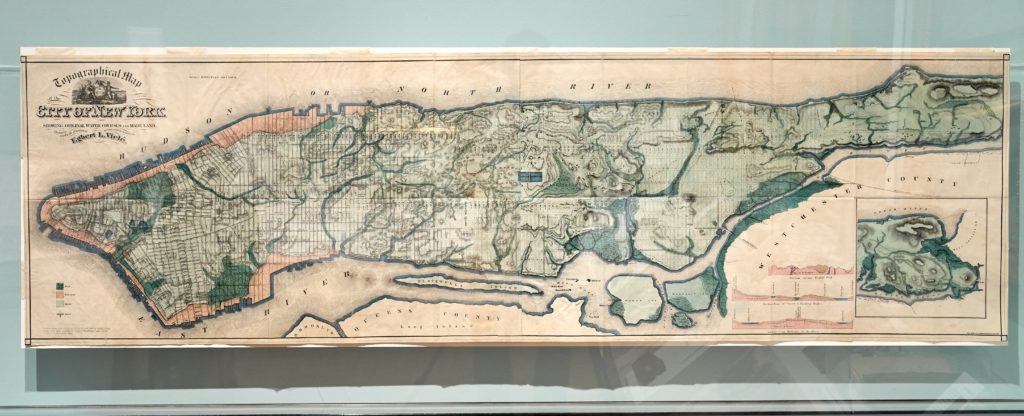

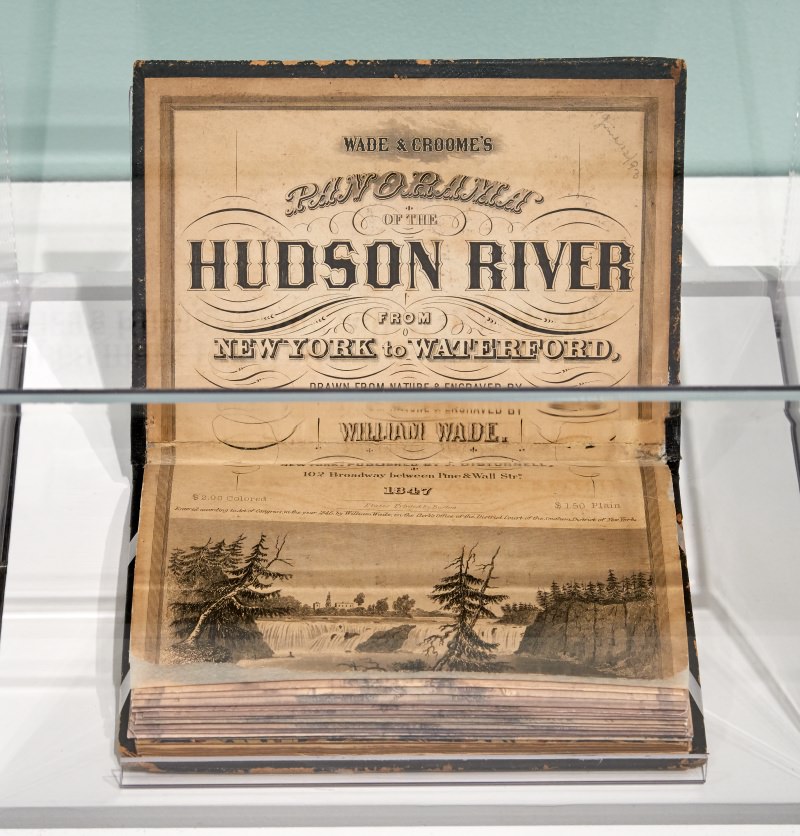

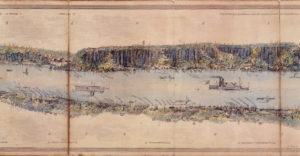

Spread before you is one of the great tourist guides of Hudson River history. With the Panorama of the Hudson, first published in 1845, steamboat and armchair travelers could consult an exquisitely detailed depiction of the river landscape.

The Panorama extended from New York City to the last navigable point of the river near Troy. Its fold-out map plotted structures from the majestic to the pedestrian. Its commentary effusively described Hudson Valley industries and natural wonders, notable individuals, and Revolutionary War sites.

Guides like the Panorama helped mark the Hudson as one of the nation’s special places. “America’s Rhine,” some called it, after the famous German river.