INSTRUCTIONS

To explore the exhibit using the 360 viewer, enter by clicking on the panoramic images of the gallery. Once you enter, you can view the entire exhibit in this mode by clicking, scrolling, and dragging.

If you prefer to scroll through the exhibit offerings section by section, find the objects and labels arranged in order following each of the panoramic images. Every image is clickable.

Moving around is easy. Explore by clicking and scrolling, or use the drop down menu at top to jump from one scene to another. Switch between the 360 view and the linear view at any point.

For an illustrated list of instructions, click here or select How To from the Menu at the top.

For the accompanying family guide (recommended for ages 7 and up), click here. For the student curriculum, click here.

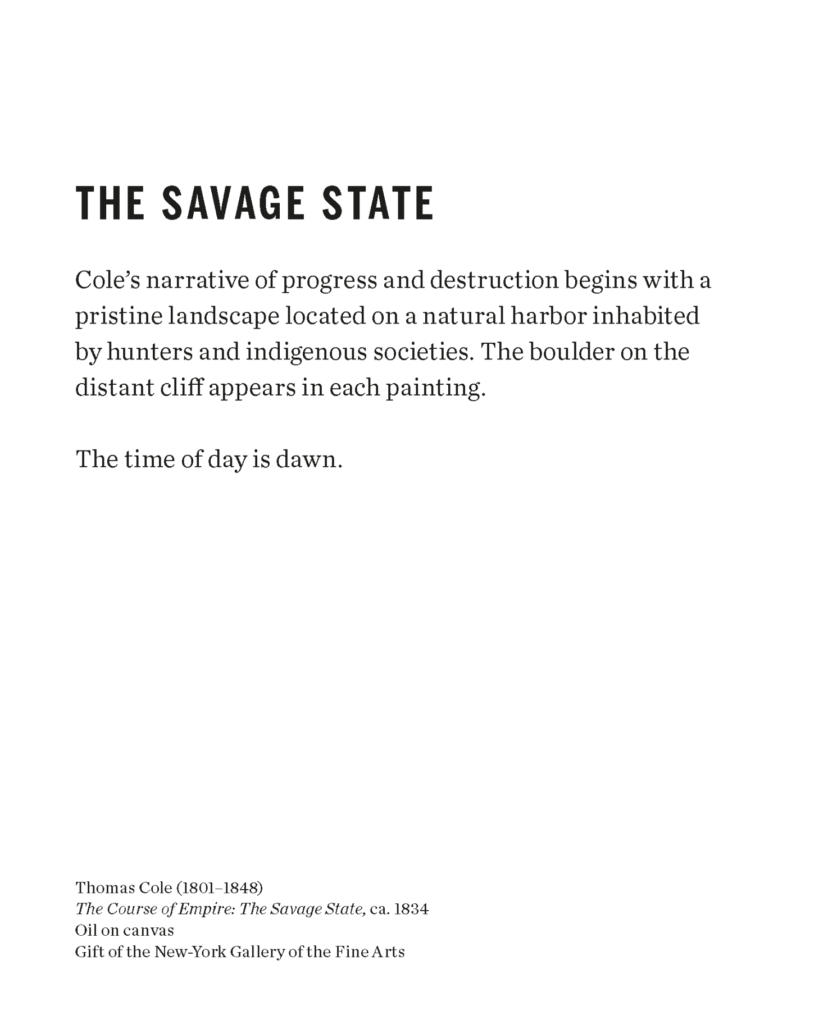

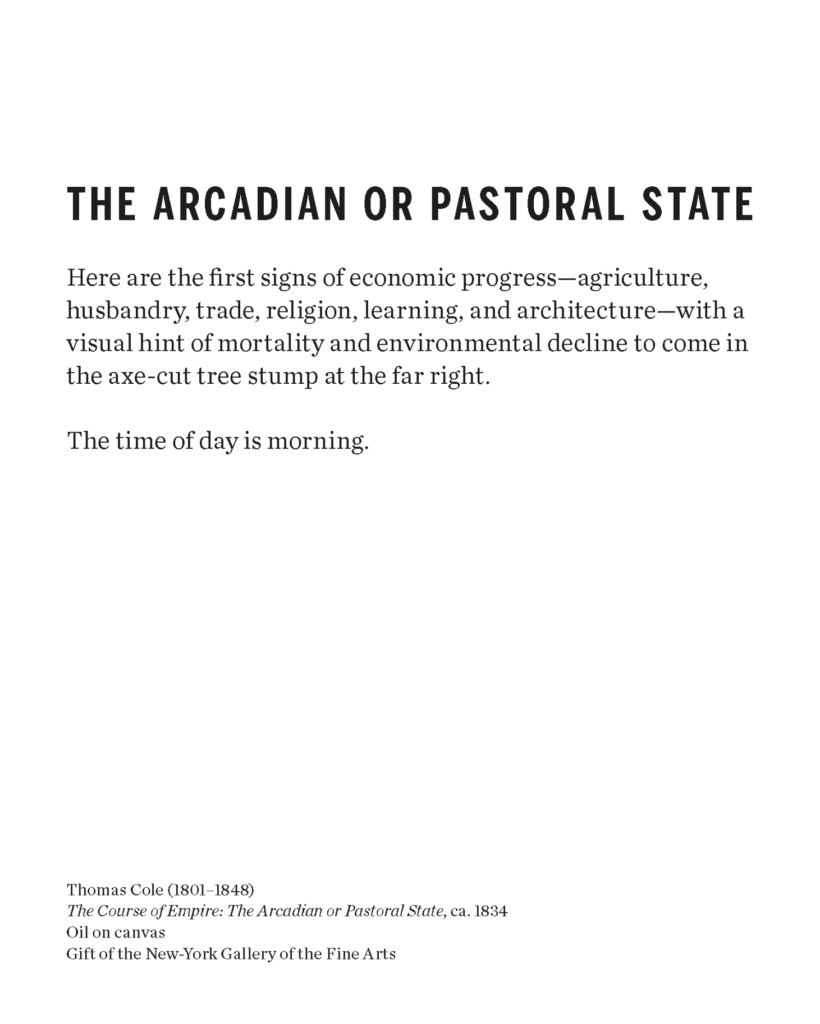

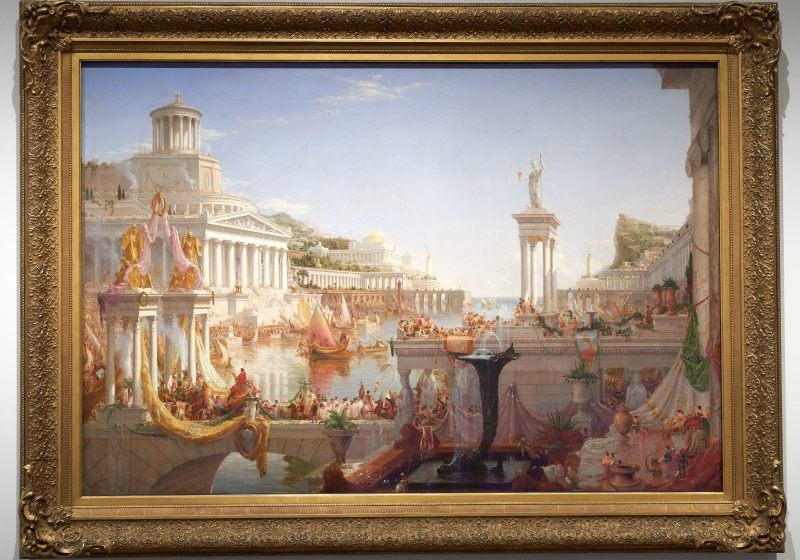

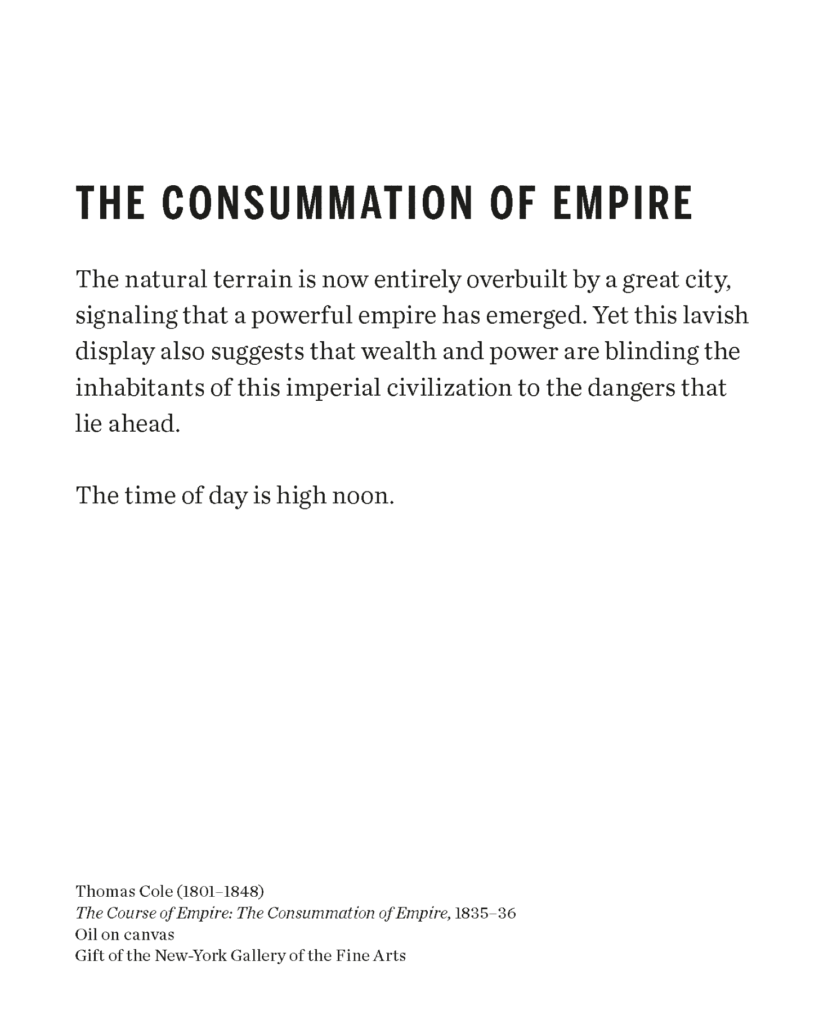

THE COURSE OF EMPIRE

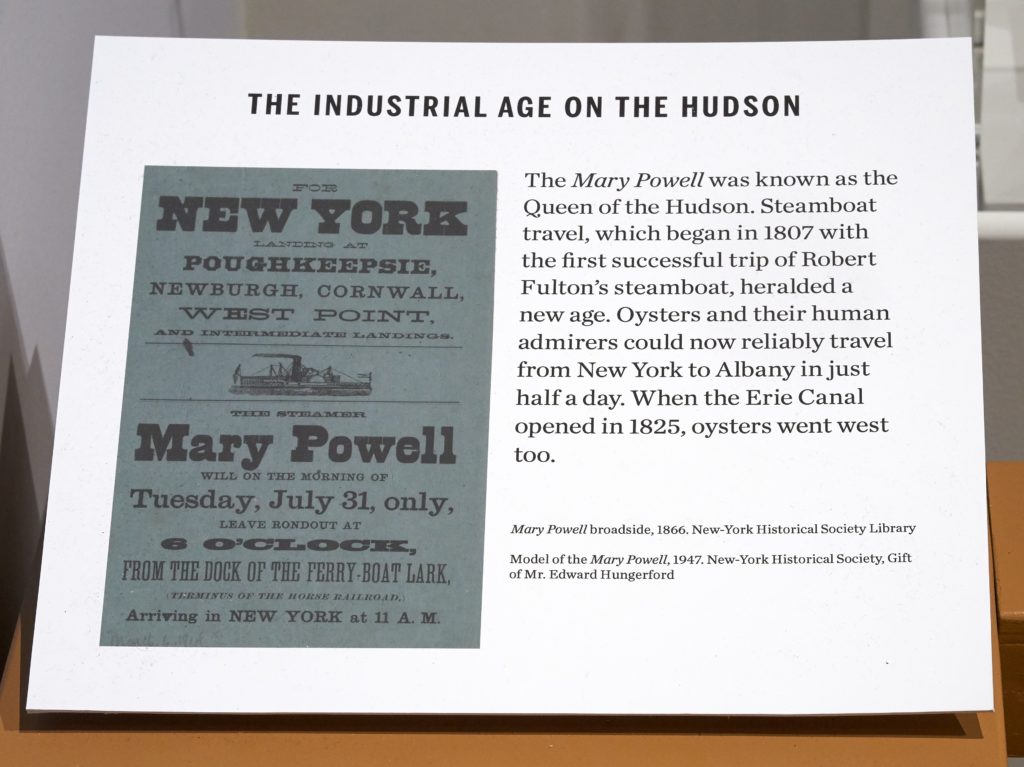

Thomas Cole portrayed the rise and fall of a civilization in The Course of Empire, his five-canvas series created in the 1830s. Cole did not identify the metropolis he depicted: perhaps he was thinking about the Rome of antiquity, or about contemporary London or New York. But when Cole turned to the written word to castigate human hubris, as he did in his 1836 "Essay on American Scenery," he situated his criticism in the Hudson River Valley.

Relocating, in 1836, from New York City to a permanent home in Catskill, a village on the Hudson, Cole witnessed firsthand the damage that railroad construction, leather tanning, and other local industries were inflicting upon the forests. "The ravages of the axe are daily increasing," he wrote. "The most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilized nation."

Cole's love for the Hudson Valley region informed his work and inspired the group of landscape painters later named the Hudson River School. He was one of the first to grapple with portraying the consequences of altering nature to meet human needs and desires. In later years, others would reflect upon similar concerns, and some would take action.

What we would today call "environmental awareness" emerged early on along the Hudson. The intensity of the industrial activity, and its degrading impact on a river valley that had long been celebrated for its beauty, made the stakes particularly high.

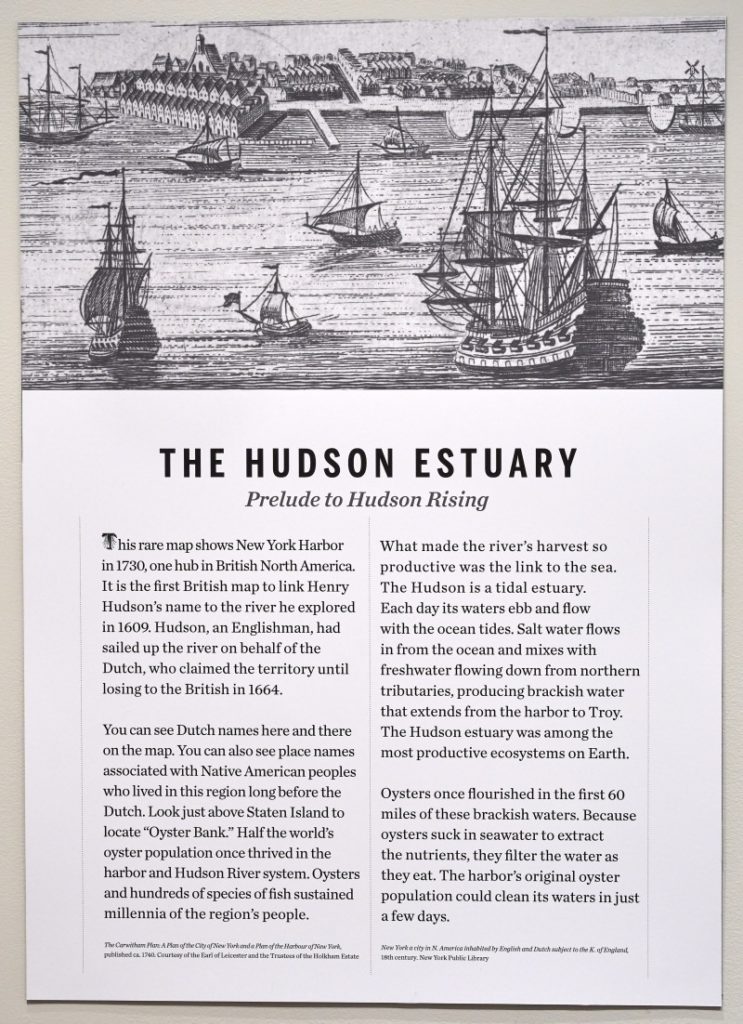

The Hudson Estuary: Prelude to Hudson Rising

This rare map shows New York Harbor in 1730, one hub in British North America. It is the first British map to link Henry Hudson’s name to the river he explored in 1609. Hudson, an Englishman, had sailed up the river on behalf of the Dutch, who claimed the territory until losing to the British in 1664.

You can see Dutch names here and there on the map. You can also see place names associated with Native American peoples who lived in this region long before the Dutch. Look just above Staten Island to locate “Oyster Bank.” Half the world’s oyster population once thrived in the harbor and Hudson River system. Oysters and hundreds of species of fish sustained millennia of the region’s people.

What made the river’s harvest so productive was the link to the sea. The Hudson is a tidal estuary. Each day its waters ebb and flow with the ocean tides. Salt water flows in from the ocean and mixes with freshwater flowing down from northern tributaries, producing brackish water that extends from the harbor to Troy. The Hudson estuary was among the most productive ecosystems on Earth.

Oysters once flourished in the first 60 miles of these brackish waters. Because oysters suck in seawater to extract the nutrients, they filter the water as they eat. The harbor’s original oyster population could clean its waters in just a few days.

Generous support for this exhibition provided by First Republic Bank, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Lily Auchincloss Foundation, William T. Morris Foundation, Inc., Shaiza Rizavi and Jonathan Friedland, The Hart Charitable Trust, and Dr. Charlotte K. Frank in memory of Pete Seeger.

Exhibitions at New-York Historical are made possible by Dr. Agnes Hsu-Tang and Oscar Tang, the Saunders Trust for American History, the Seymour Neuman Endowed Fund, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. WNET is the media sponsor.